Today we explore transaction encoding.

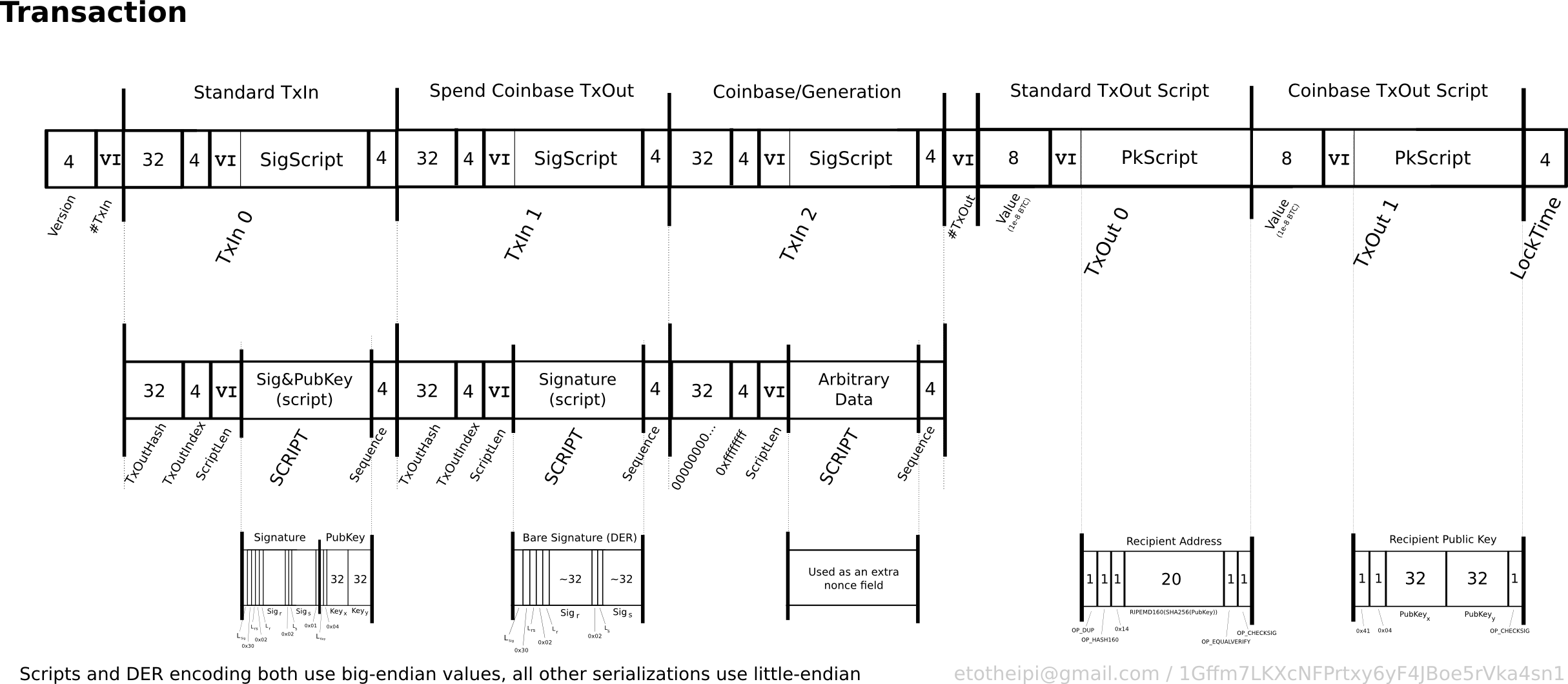

Above: Bitcoin transaction, from here.

Satoshi, for all his genius, made some strange choices. If we could hard fork, we could shrink most transactions by about 20%.

Usually a hard fork is a non-starter, but a LargeBlock Sidechain starts with a blank slate. So there we could make the savings count.

Part 1. The Two Mandatory 4-Byte Fields That No One Uses

A. nLockTime

Each transaction must have a 4 byte “nLockTime”. Like “postdating” a check, it stops the transaction from being “cashed” until a certain future time.

Over 99.9% of our users, have never intentionally used this feature. (Literally so, see here.)

If a user doesn’t need it, we can allow them to make a txn-version which never uses those 4 bytes.

B. nSequence

Similarly, each transaction input is required to have a 4 byte “sequence number”.

Satoshi indicates that this was intended to allow for rapid iterations of txn versions, of which only the latest would be included in a block:

An unrecorded open transaction can keep being replaced until nLockTime. It

may contain payments by multiple parties. Each input owner signs their

input. For a new version to be written, each must sign a higher sequence

number (see IsNewerThan). By signing, an input owner says "I agree to put

my money in, if everyone puts their money in and the outputs are this."

There are other options in SignatureHash such as SIGHASH_SINGLE which

means "I agree, as long as this one output (i.e. mine) is what I want, I

don't care what you do with the other outputs.". If that's written with a

high nSequenceNumber, the party can bow out of the negotiation except for

that one stipulation, or sign SIGHASH_NONE and bow out completely.

And indeed, this is used in LN channel management (along with nLockTime). Today, nSequence works like this:

Regarding the implications, if the nSequence is:

= 0xffffffff, then the transaction is final no matter the nLockTime.

< 0xfffffffe, then the transaction signals for RBF.

< 0xefffffff, then the transaction signals BIP68 relative locktime.

That’s all well and good.

But 99+% of regular people, sending to each other on-chain, use neither nLockTime nor nSequence.

Therefore, in a “standard” 1-input-2-output txn, there are 8 irrelevant bytes.

Part 2. Aggressive Standardization of Scripts

A. Outputs – A Review

Let’s review how Bitcoin works.

If Alice wants to send money to Bob, she asks Bob for his “address” (or for something similar). Wallet software does not actually use this “address” per se – instead, it transforms the address into “locking conditions”. (These “locking conditions” are sometimes called the output’s “script”.)

From 2009 until 2017, these locking conditions mostly looked like this:

OP_19 OP_DUP OP_HASH160 [X] OP_EQUAL OP_CHECKSIG

Where X equals: The "hash160" -- 160 bits (20 bytes)

that correspond to Bob's BTC address.

That’s called P2PKH. (“Pay to PubKey Hash”).

(I have included the OP_19 which indicates that the length of the locking conditions is 0x19 = (16*1)+9 = 25 bytes. And also the OP_14 which indicates that the length of X is 0x14 = (16*1)+4 = 20 bytes. People often overlook these.)

Almost everything was P2PKH. The remainder was P2SH. (“Pay to script hash.”)

More background: If you are interested, you can convert Addresses <–> Hash160 using this site. The “blank” private key (the private key equal to the sha256 hash of “” (aka “nothing”)) has address 1HZwkjkeaoZfTSaJxDw6aKkxp45agDiEzN and Hash160 b5bd079c4d57cc7fc28ecf8213a6b791625b8183. (Addresses do not appear anywhere in the blockchain, only Hash160s. Addresses have user-interface features [such as checksums], but these are deleted before adding the transaction to the blockchain.)

More background: These “locking conditions” are called “outputs”. The UTXO set is the “[U]nspent [T]ransaction [O]utput [S]et” – it is basically a huge 2-column table, listing: [1] all the coins, and [2] who owns them.

Now, why do I bring this up?

B. Satoshi’s Inefficiency

Satoshi’s system forces users to spell out the whole script, every time.

In other words, imagine you looked at the UTXO “table”. You would see column one… a list of coin-amounts [8 bytes], all different. But column two would look like this:

OP_19 OP_DUP OP_HASH160 [X] OP_EQUAL OP_CHECKSIG

…repeated over and over again. Only the X’s would be different.

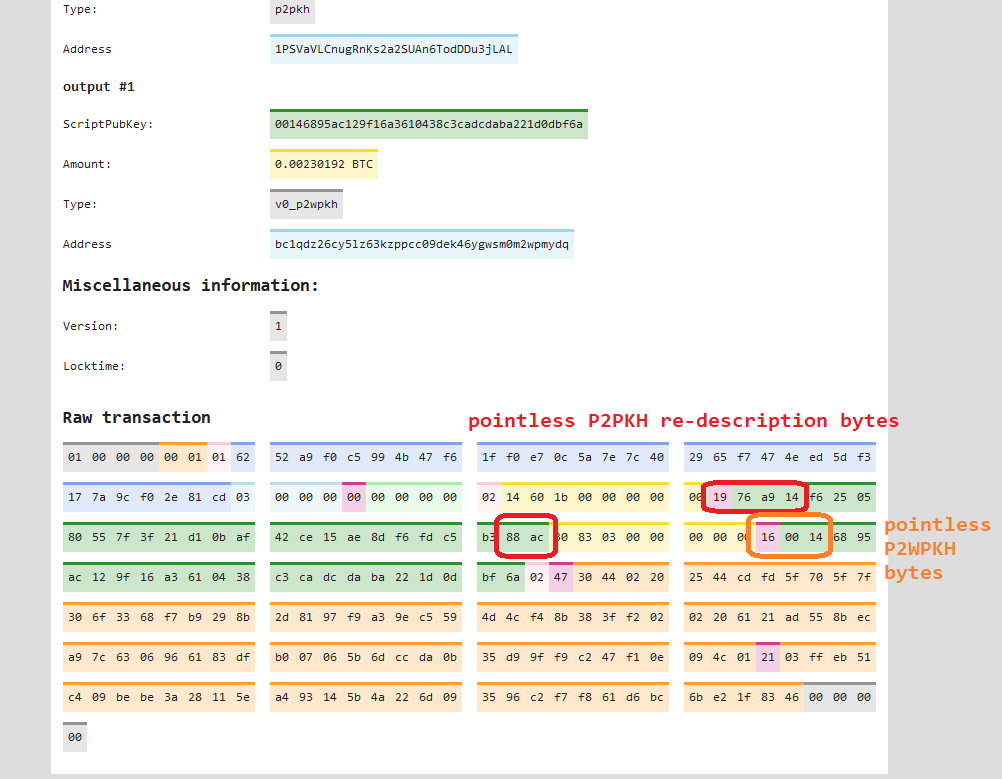

Above: Simpson’s chaulkboard joke. I got it from here.

This is inefficient because each of those “OPs” requires one byte. So, outputs are: 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + [20] + 1 + 1 = 24 bytes.

There is a pointless “1976_a9_14…_88_ac” repeated over and over.

For P2SH, there is a pointless “17a9_14…_87” repeated over and over.

Therefore, 6 bytes are used, to convey one single piece of information: “It is a P2PKH-locked coin”. And 4 bytes are used, to convey “It is a P2SH-locked coin”. One single version-byte, would cover both use cases (with room for 254 additional use-cases). All we need to do is specify them in advance, and hardcode them into the source code.

In fact, if there is ANY other way of indicating the txn-type, then we can cut it down to zero-bytes. SegWit uses one such way…

C. SegWit / Taproot Addressed This Inefficiency

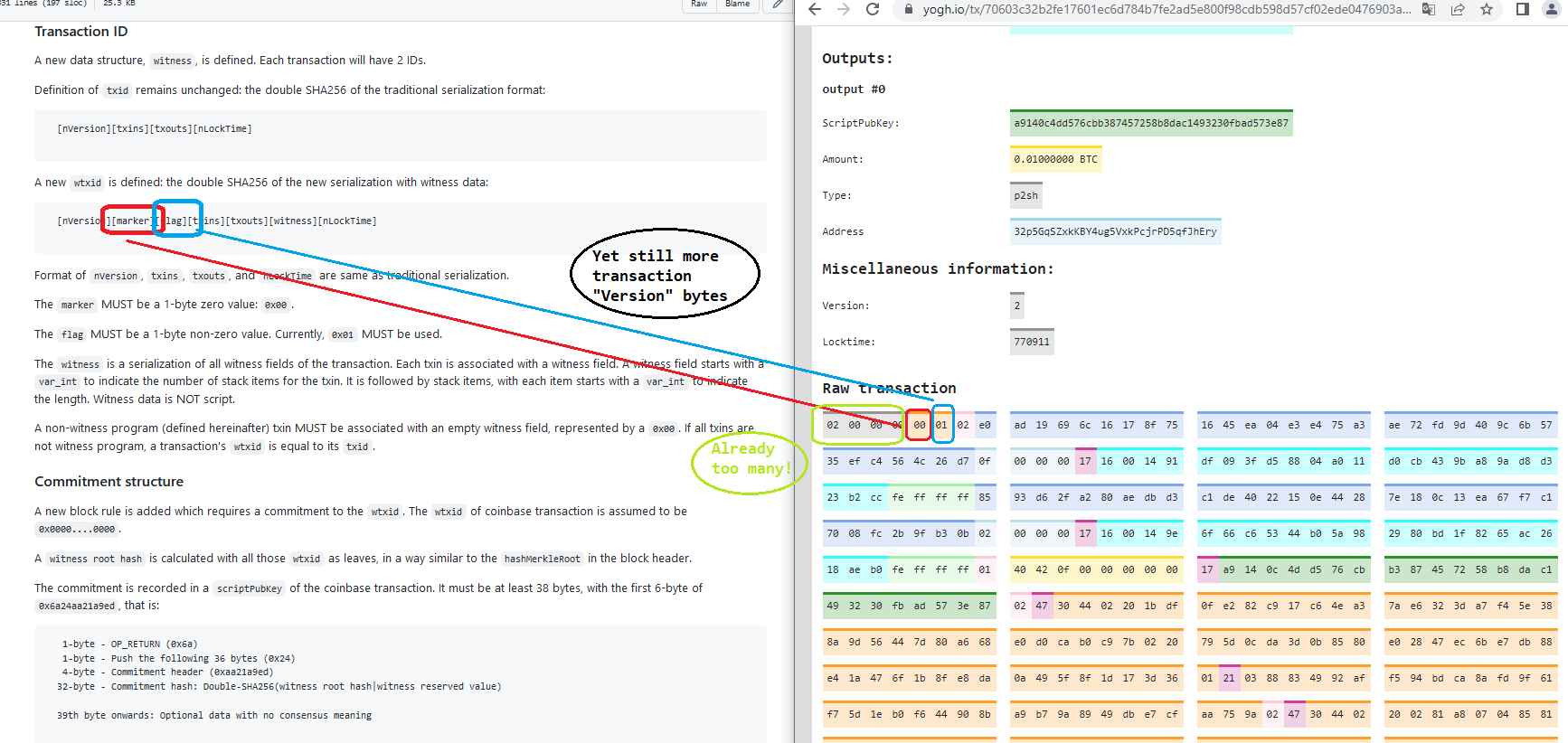

SegWit did away with some of these wasted bytes.

See for yourself: If the witness program is 20 bytes, it is just interpreted as P2WPKH (which is SegWit’s version of P2PKH). If instead it is 32 bytes, then it is interpreted as P2WSH (which is SegWit’s version of P2SH).

( See! Even pwuille says I was right. )

D. We can go much Further

But SegWit was unable to push the limit to its theoretical minimum.

Sadly, SegWit outputs still have a redundant “16_00_14…”. That corresponds to:

- One byte [0x16] to push 22 bytes

- One byte to describe the segwit version (“00” for SegWit, “01” for Taproot)

- One byte [0x14] to push 20 bytes

In other words: 3 bytes to convey “this is a P2WPKH output”. We could have gotten away with just one byte!

On top of that, SegWit txns must add 2 bytes to the txn version number. (These are the “marker” and “flag” bytes.)

Which is unfortunate, because the txn version number is already 4 bytes …absurdly large.

As we will now see.

Part 3. The Pointless Overkill That is a 4-byte Version Number

Here we will shrink 8 bytes to just one.

A. Wasted Overhead

Every single Bitcoin transaction, has:

- 4 bytes of “version”

- (Now), 2 extra bytes [marker and flag]

- 1 VarInt byte (at least) to specify the number of inputs

- 1 VarInt byte to specify the number of outputs

As far as I can tell, all of these 8 bytes are wasted.

The current version system uses 4 bytes – this can describe 2^(4*8) = about 4.3 billion types of transaction. Absurd overkill.

B. Eliminating the VarInts

Two bytes are used, to specify the number of inputs/outputs. This is overkill.

For starters, >50% transactions are one fixed type: 1-input-2-output. See for yourself.

The remainder, tend to have: fewer than 5 inputs / 5 outputs.

Furthermore, we can cut corners, when it comes to Outputs. Usually, there are exactly two outputs: one to make a payment, and one to make change (paid back to you). Or else, someone is doing a 5-in-5-out CoinJoin. Very rarely does someone pay to many outputs.

So, with just one byte, we can encode all of this. Without losing Satoshi’s OG overkill functionality.

C. Preserving all Satoshi’s Functionality – A “VarInt Version Byte”

First, we want to preserve Satoshi’s 4-byte version system if we need it.

So we will add a trick: if the first byte is all 1’s, then check the next three bytes.

bit "VarInt" Escape

--- -------------------

1 0 if: 1

2 0 1

3 0 1

4 0 1

5 0 1

6 0 1

7 0 1

8 0 1

=== then: check next 3 bytes for this txn's true Version #

8 bits = 1 Byte

With this rule, we preserve the ability to specify 16,000,000+ transaction types. Currently we only use three, so many millions should be enough.

We can also meet Satoshi halfway. With this rule: if the first byte is a certain value, then check only the next two bytes.

bit "VarInt" Escape

--- -------------------

1 0 if: 1

2 0 1

3 0 1

4 0 1

5 0 1

6 0 1

7 0 1

8 0 0

=== then: check next 2 bytes for this txn's true Version #

8 bits = 1 Byte

We again shave off a byte, but can still express many txn types. If there is going to be a version number in front of every output, I honestly do not see why we need a version number in front of the Txn at all. But we can still have one if we want it.

Now, we will make use of our one byte. It will descrbie the quantity of both inputs and outputs.

D. Our 1-Byte Version Number

It could look like this.

bit Meaning

--- ------------

1 0 [reserved]

2 0 [ input quantity 0 0 1

3 0 ... 0 0 1

4 0 ... 0 0 ... 1

5 0 ... ] 0 = 1 input 1 = 2 inputs 1 = 16 inputs

6 0 [ output quantity 0 0 1

7 0 ... 0 0 ... 1

8 0 ... ] 0 = 1 output 1 = 2 outputs 1 = 8 outputs

===

8 bits = 1 Byte

This allows us to have as many as 16 inputs, and 8 outputs. And we even have one bit to spare!

We have to be careful to not accidentally trigger the VarInt escape. We are allowed to have a transaction with 16 inputs, OR one with 8 outputs OR one with the reserved top bit set to “1”. We can take any two of those, but not all three together. (If we take them all, then we fill the txn vector with 1s, which will trigger the VarInt escape we just discussed.)

The VarInt escape is crucial because, on the off-chance someone really wants to encode 200 inputs (or more), they can just trigger the original 4 byte version number, and describe “classic” satoshi-style txn, with VarInts and the like. Since 200 inputs will be an enormous transaction (and an extraordinarily rare one), no one will shed a tear over the restored 3 txn version bytes.

Part 4. Smaller Inputs

An input = a txn ID + 4 bytes describing the position of the output within that TxID.

Again, this is absurd overkill.

A. Why 4 Bytes?

One single byte can count up to 256. With merely one, you can pay 255 people, and pay yourself change.

Who is making these transactions, that pay so many people at once?? More than 256?? It also has terrible privacy implications.

The smart thing: cap outputs per txn at 256. Use one byte only.

To ensure that we never regret doing this, we can still allow the old way. On an ad hoc basis. How? Simple: we set one of the special “legacy” txn version numbers (those with 2 or 3 bytes), to produce more than 256 outputs. And a different special version number to spend / select outputs outside the 1-256 range.

With that regret out of the way, we can now cut 3 bytes from every txn input. We save 6 bytes out of a 1-input-2-output txn.

B. [Added April 10] Why the whole TxID ?

What about referring to inputs using just a prefix of the txid

instead of the full 32 bytes? We can get away with just 8 bytes,

probably. If there is more than one tx on the utxoset with the

same initial 8 bytes the verification code can try both.

Indeed, even 8 bytes is overkill. It would allow for 2\^(8*8) = 1.84 e19 distinct UTXOs, many billions per each Earth human.

4 bytes gets us to 4.29 Billion, which would probably be enough (given that not all Earth-transactors will be on a single chain, anyway, even in the most onchain-friendly scenario).

Thus, we shrink inputs from 32+4 bytes, to 4+1 bytes.

Part 5. Aggressive Standardization

If we use Schnorr for everything and force everything to be either P2SH or P2PKH, then we never need to describe lengths of things.

We also don’t need to hash things, and later reveal them. We just know a Schnorr pubkey is coming (when the coin is locked) and a Schnorr signature will unlock it.

Part 6. Total / Conclusion

For a standard 1-input-2-output P2PK transaction, we have now gone from:

4 -- version

2 -- marker & flag

1 -- number of inputs

First Input

32 -- TxId

4 -- index

1 -- pointless "00" empty byte

4 -- pointless sequence bytes

First Witness

1 -- number of witness items

1 -- length of signature

71 -- signature

33 -- length of pubkey

1 -- number of outputs

First Output (P2PKH)

4 - pointless "19_76_a9_14"

20 - Hash160

2 - pointless "88_ac"

Second Output (P2SH)

3 - pointless "17_a9_14"

20 - Hash160

1 - pointless "87"

4 -- pointless locktime

========================

209 Total

…to:

1 -- version

First Input

4 -- TxId

1 -- index

First Witness

64 -- signature

First Output (P2PK)

1 - output version

33 - pubkey

Second Output (P2PK)

1 - output version

33 - pubkey

=====================

138 Total

We managed to shrink this transaction to 66.0% of its original size. By being more efficient, it is as if our 1 MB block size was instead a 1.515 MB block size.

…well, I guess that wasn’t a big improvement! But every little bit helps!

And hopefully you learned something new today!

Special thanks to yogh.io , my favorite block explorer.

comments powered by Disqus