pretext - prē′tĕkst″ (n.) A reason or excuse given

to hide the real reason for something.

--Thunder Genesis Block(?)

1. Motivation

Bitcoin (BTC, the currency) in its current form can scale – enough to process every txn in the world! It just needs the right combination of layer2s.

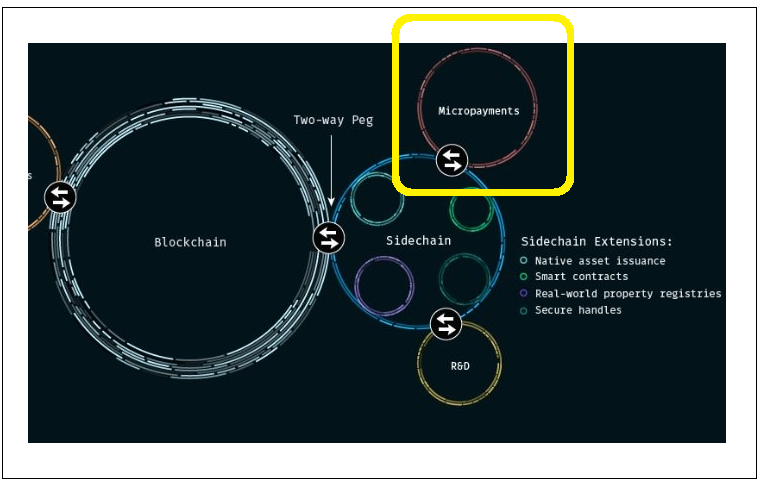

This post will introduce “Thunder” – a network of largeblock sidechains. By “largeblock sidechain” I mean that the sidechain network is mostly-identical to its mainchain network, just with larger blocksize/sigops limits.

A. Today’s Layer-2s

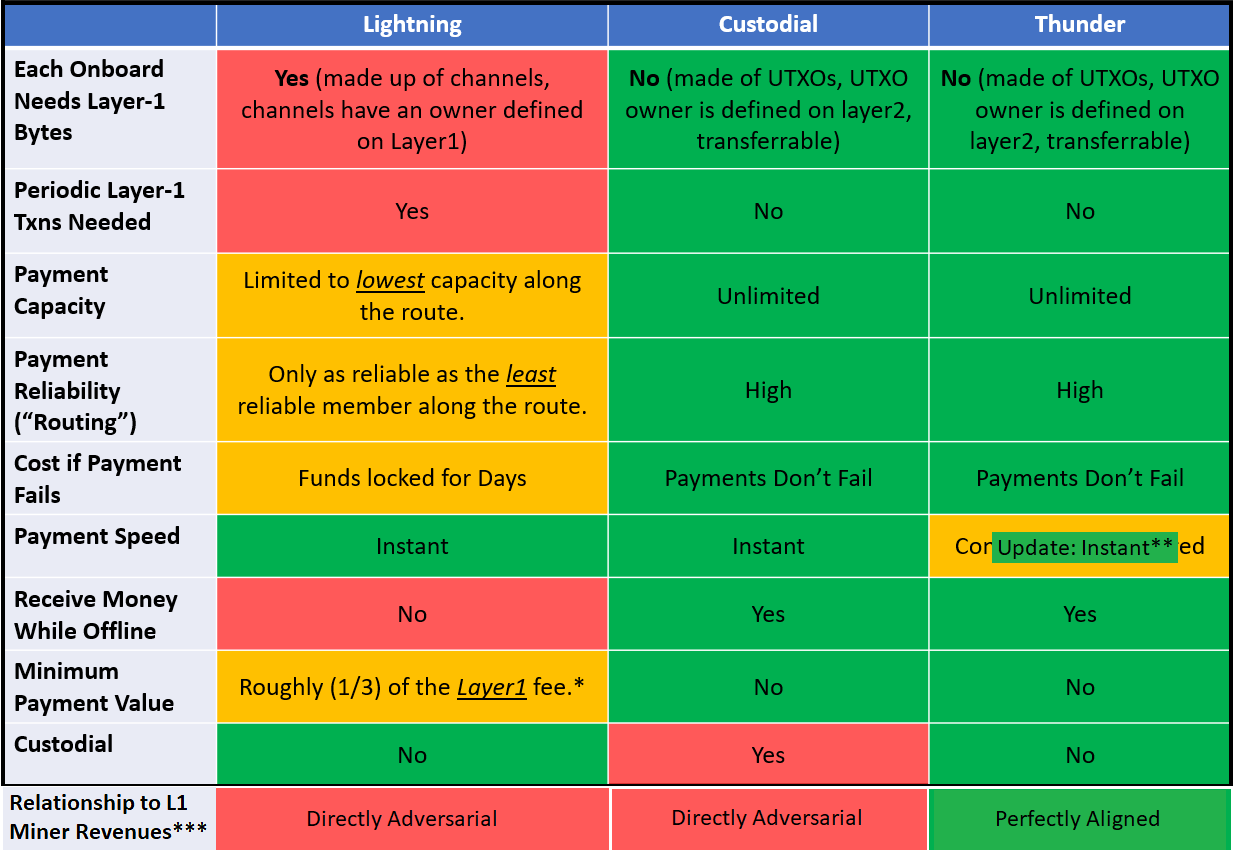

Lightning Network provides some of the solution, but the main scalability benefits of a layer 2 are lost if layer-1 bytes are required to onboard each user1. Custodial solutions (as originally envisaged by both Satoshi and Hal Finney in 2010) also work very well, and are user-friendly… but the user is then beholden to the custodian.

Here is a table comparing Thunder to those two more-prominent Layer2s (LN and Custodial):

- * See here. (Previously here. 75/222 = .337.)

- ** Update (Sept 2023): It is possible for a Thunder txn to settle instantly, using forfeit bonds. You will need to combine this with a full node (similar to a LN watchtower node).

- *** Update (Sept 2023): Txns on Thunder will pay a txn fee to L1 miners, but LN/Custodial do not. Since we expect (eventually) high Bitcoin adoption, an LN-only strategy is doomed to an eventual war between L1 and L2, over billions per year in txn fees (maybe even 100B-200B). Thunder does not have this problem. See also.

The main problem with custodial Bitcoin, is that gold already tried that strategy and, after a short while, people stopped caring about the underlying gold and cared more about the custodian’s ledger (ie, the custodians opinion of who had how-much-money). More.

Statechains are another layer2 with very interesting and unique properties. Namely, they do not require layer1 bytes to onboard each new user, but they do require that every individual UTXO in use “in” the statechain be onboarded via layer1. Which is better than LN but still problematic.

SNARKS do not help with scalability at all, because they do not solve the so-called “data availability problem”. There is no way to use the SNARK to recover the sequence of events that led to its creation. There is also no way to audit the SNARK, to make sure that it is working correctly, without also having all of the original data on hand. Thus, SNARKS do not help with scalability, are probably only useful as an enhancement to SPV-level security.

B. A New Framework

An old critique, of scaling-via-blocksize-increase, ran as follows:

It suggested that capacity increases were naive, unprincipled, undisciplined, and that they would lower the quality of the whole network. In contrast, enforcing property rights (ie, enforcing the 1 MB blocksize limit) might seem cruel, but overall this “tough love” is the only way to build a reliable, sustainable, high-quality system.

That critique was accurate, and I don’t mean to overthrow it!

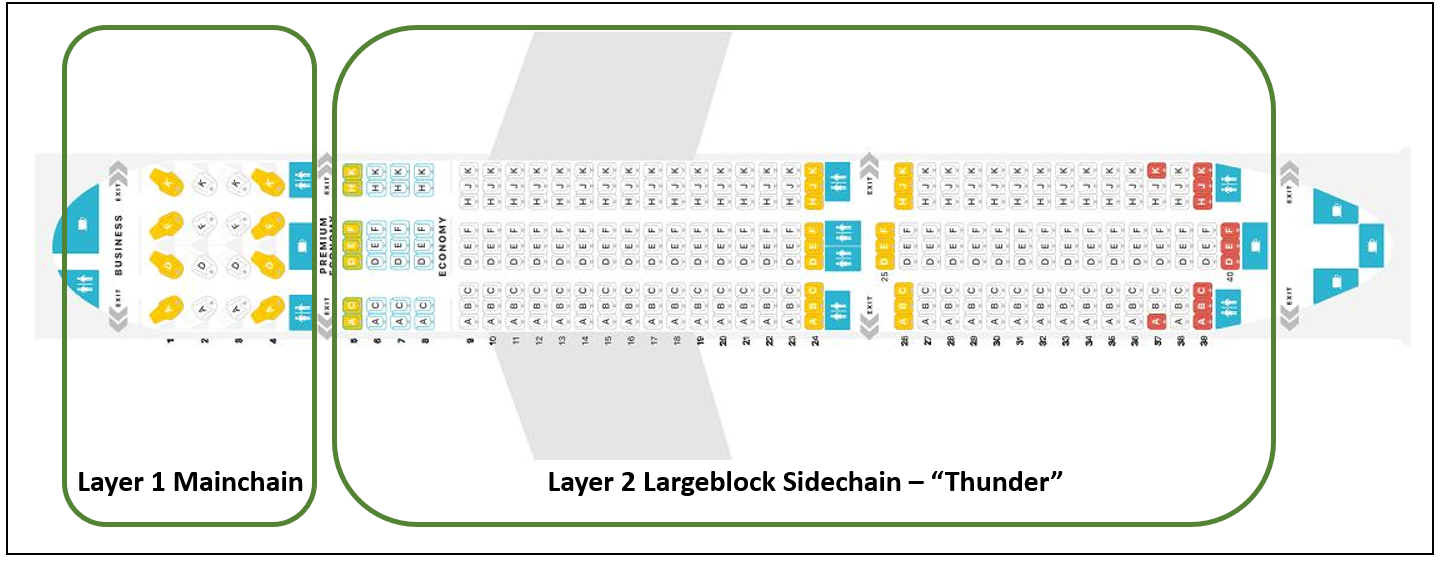

But I do want to change it slightly. Instead of a train “100% clean” vs “100% overcrowded”, I would rather people think of a situation where the same vehicle has different sections: First Class, Business Class, Coach, etc. In that model, the passengers have a different experience in many important ways, but they also have some things in common.

First/Business class is the small block “layer 1” – expensive but high-quality; cheap nodes, reliable access to the blockchain, high txn fees.

Coach would be the large block “scalability sidechains” on layer2 – cheap to use; but a more problematic full node experience, less decentralization.

But crucially, the two “classes” can benefit by sharing the same plane. In the sidechain analogy, this is the two chains sharing the 21 million coin limit, and sharing hashpower, and being inter-operable (meaning that people who usually fly 1st class can choose to save money by downgrading to coach, and the people who usually fly coach can choose to upgrade their experience by paying for 1st class). In a world without-sidechains, people have to fly on an airplane that only has one class for everyone.

Transactions in the real world take all shapes and sizes. Not all of them require the same level of trust, and not all of them can bear to pay the same fee-overhead. See also.

C. The Decentralization Gambit

(Added 2/6)

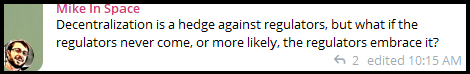

The one-size-fits-all full-decentralization approach actually makes Bitcoin vulnerable. Committing to a policy of “very decentralized only”, is a gamble. It is a bet, saying: we live in a hostile world.

If instead the world is nice, then we’ll lose the bet.

Decentralization is useful for resisting powerful people like governments, mafia, dictators, tech-giants, cancel culture etc. To obtain this precious decentralization, Bitcoin must sacrifice other precious things: ease-of-use, txn-cost, engineering-effort etc.

Thus, in a world of friendly “powerful people” who promote all cryptocurrencies, the advantage goes to less-decentralized coins (ETH, BSV, etc).

Worse, the “powerful people” can be aware of this and use it against us. At first they can bide their time, allowing all cryptocurrencies to thrive, and thus (via network-effects) allowing the least-decentralized coins to use their natural advantages to eventually displace the others, including BTC. Once decentralization has purged itself from the cryptocurrency world, the “powerful people” can then move in with a “light touch” and see what they can safely get away with (using the network-effects as an anchor). Once that is accomplished, they can slowly keep tightening the noose from there. See also.

This entire risk is avoided, if users can choose the level of decentralization they want (which is what Thunder allows). In a Thunder-world, we do not need to worry about “losing” the bet (that the “world is mean”). If instead the “world is nice”, then it only means that a higher portion of BTC’s 21M coins will be on less-decentralized sidechains. If the world switches from nice to mean, then the coins will switch networks from less-decentralized to more-decentralized. It would NEVER effect Bitcoin’s competitiveness in the wider cryptocoin marketplace, and the layer1 mainchain would never go “out of business”.

D. “Bitcoin vs. The Banks”

The phrase “Bitcoin vs The Banks” is a common Bitcoin slogan.

But unless “Bitcoin” (regarded broadly) has a complicated hierarchical payments system –with many “layers” and lots of netting among them– there is no possible way it can pose a serious challenge to the legacy banking system.

( It may pose a serious challenge to something else, namely gold. Which is a good start – an excellent start! But gold is only worth 7.5 trillion today. That’s just a tenth of global broad money, which is at least 80 trillion. Internationally, everyone borrows and lends in US Dollars. Dollars are required to pay those debts, forcing people to work toward obtaining them. That’s a strong network effect! That’s what we should want for Bitcoin someday! )

To me, “money” is payment-centric. This explains why laypeople always ask: “Bitcoin…? …but who accepts it?”. Money is how we keep track of who owes favors to whom. It isn’t a medium of exchange or a store of value, it is a method of payment.

Again, this isn’t to say that smallblock-ism is wrong. I am a smallblocker – Bitcoin should fight tooth-and-nail to preserve its “Swiss Bank Account in your pocket” qualities.

But unless there is some way for Bitcoin to scale to handle all the world’s transactions, Bitcoin will never achieve its full potential.

First, let’s ask: how many transactions?

2. How Many Transactions Are We Talking?

A. United States

We can see from the 2019 FED Payments Study, Table B1 that the average “card” payment in 2018 was $54. And that 131.2 billion such payments were made.

We can also see from the 2018 FED CPO DCPC Survery, Figure 7 that, by volume, cash payments are about 40% of “card” (Credit and Debit) payments.

This would imply (131.2*1.40)= 183.68 billion payments per year (card+cash), in the US. Since there are 52,560 blocks per year, this amounts to ~3.5 million txns/block. If each txn is 250 bytes, this implies blockspace requirements of 875 million bytes, or 875 MB.

We will need to beat the “average rate” by a significant margin (transactions are not evenly spread out throughout a 24 day – most are during daylight hours). But nonetheless, the actual expected usage of the network (determining the bandwidth/storage/cpu requirements) is the average rate.

B. The World

According to the World Payments Report (2018), Figure 1.1, Non-Cash txns numbered 482.6 billion / year, in the year 2016; and showed growth of 9.8% per year.2

At that rate, there will be 770 billion non-cash transactions/year in the year 2021, which corresponds to a TPS rate of just under 25,000 transactions per second. We can again adjust by 40% to include the cash transactions, which would take us to 35,000 TPS.

That figure will grow over time, of course, but we can use it as a benchmark for today.

3. How to Achieve that Level of Txn-Throughput?

A. Team of Sidechains

Well, by using all our layer2s at once, of course.

But what I have in mind is: several largeblock sidechains, added in a sequence. We start with one sidechain – it can have perhaps a 10 MB blocksize, which is programmed to rise slowly to 1 GB over a period of 10 years.

If more capacity is needed, we can either wait patiently (for the 10 MB blocksize to rise over time toward its final destination of 1 GB). But, more relevantly, at any time we can also just add another sidechain.

I call this strategy “Thunder”, and each sidechain a “T-network”.

B. How it Works

As I mentioned, as time goes on we can just add more “Thunders” in parallel.

Mainchain (Layer-1 SmallBlock Bitcoin)

|

--------|----------|------------|--------|--------|----------|---------|--------|------|--

Thunder Thunder.Asia T.Europe T.China T.India T.Arabia T.Alt T.Africa T.USA

Time ---> 2023 2024 2028 2030 2034

For efficiency, there should be many more intra-Thunder txns than cross-Thunder txns. Thus, the obvious thing is do emulate the banking networks of the past, and partition the networks by geographic region. See: OCA.

How might we get from where we are now, to a future of many largeblock sidechains?

It starts with the creation of the first largeblock sidechain. This sidechain eventually fills up. Thus, a new second largeblock sidechain will be needed.

Old users will likely not want to leave the network they are on, so in general I would expect a new network to be created by the second-largest group in a crowded old network (see below). Thus, if USA are the early adopters of Thunder, I would expect them to stay on the “Thunder” network (the first, and oldest network), just as Americans telephones have the country code “+1”. Eventually, (hypothetically, in the year 2034 as shown above), the first network might become too crowded with non-Americans (despite the numerous non-American T.networks), and Americans would want newer features, so the USA-centric network would be born quite late.

Note that every time a new network is created, transaction fees drop for everyone (as, for example, when T.India is created, all the Indian users quickly migrate there from “Thunder”, “Thunder.Asia”, and “T.China”).

The question of “who has to leave and start their own network, and who stays on the old network”, may become political. But this conflict is likely to work itself out. First of all, the migrants can start afresh with a new blockchain, getting all of the latest tech-improvements (like switching from 4G to 5G). Second, there is a non-political criterion – whichever members of the old network, who are least able to tolerate high fees will be the ones that are motivated to move on (and they will then take their trading partners with them). So, this process will probably be self-regulating.

C. Realism

This scheme mirrors the actual structure of today’s monetary system. Which is probably a good sign.

Thunder Thunder.Asia

\ /

\ /

\ /

Mainchain (Layer-1 Bitcoin), Smallblock

/ \

/ \

/ \

T.Europe T.China

US Federal Reserve Bank of Japan

\ /

\ /

\ /

Bank of International Settlements

/ \

/ \

/ \

European Central Bank People's Bank of China

“Looking at the map, it’s quite apparent that the largest economies are the least open by this definition. But this is quite natural: Because they are so large, much of their trade is internal.”

From here.

Above: Chalkboard sketch of 1800’s era banking network. Different local banks net out payments and settle with each other in a central clearinghouse. From this video.

Above: List of Warcraft III servers (US East, US West, Europe, Asia). You play on the server that matches your location, for less lag and greater likelihood of players speaking your language, gaming during your time zones, etc. From here.

See also: Payments Just Want to be Free

4. Other Interesting Properties of Thunder

A. Automatic Capacity Management

When T.network txn fees grow too high, anyone can solve the problem by creating a new T.network. But if that sidechain isn’t genuinely needed, it will be unpopular and fail.

B. Once-and-for-all Solution

This scheme has the advantage that it solves scaling (or at least “capacity”) once-and-for-all.

BCH, in contrast (for example), must raise its blocksize via periodic hard forks. That causes numerous BIG problems. One problem is the risk of splits (such as what happened with BSV), or of political maneuvers (such as what happened with BitcoinABC’s “IFP”).

Never-hard-fork Monochain BTC, on the opposite extreme, must hope that its current technical configuration will work now and forever into the future. Or else, it must hope that it can always succeed in central-planning its way to victory (including that the current central-planners can pick competent successors). Those two hopes are unfounded (the world is just too complex, and changes too rapidly and chaotically).

C. Technical Debt / Total Design Freedom

New T.Networks do not have to be soft forks of existing T.networks. The new code-forks can start completely from scratch if they wish.

For instance, if we had Thunder in 2014, then SegWit could have been coded as a “hard fork”. This “incompatible” version of SegWit could never have been merged into layer1 Bitcoin Core, but it could easily have been merged into whatever-Thunder-network-came-online-in-2016. This would have been a big improvement in many ways: code review, code complexity, transparency to the end user, likelihood of bugs, engineering time/effort needed, etc.

( Of course, it is probably wise for the T.networks to share as much code as possible. But nonetheless the option is there to make “hard fork”-style changes. )

D. Future Proofing / Hard Fork Wishlist / Competitive Devs / Hardware

Since each new sidechain is a completely new piece of software, there is complete design freedom.

Someone who cares about scaling (for example Roger Ver, or the “Bitcoin Foundation”) could sponsor a contest to encourage new blockchain designs focusing on scalability. The winner would be whoever produced the software with the best performance. We could even have “T.India.RogerVer” and “T.India.Blockstream” – competing pieces of software. (Indeed, they would all already be competing with each other.)

This can even be viewed as a competitive reply to those Altcoins that have committed themselves to the strategy of periodic upgrade via hard fork (such as Monero/Zcash). Now “Bitcoin” can do this as well (if, by “Bitcoin”, we mean to include all BTC sidechains).

Furthermore, each new sidechain might be paired with its own custom hardware.

ECDSA signature verification... I can imagine people

writing hardware that did ten million per second.

-Gavin Andresen, to Greg Maxwell; Nov 2015

Above: Panel Discussion-DevCore Draper University 2015, 7:54

The proponents and critics of “hardware scaling” have both, in the past, ignored the all-important distinction between “layer 1” and “layer 2”. To resist tyranny, it is indeed essential that layer-1 Bitcoin full node software run on hardware that is easy to obtain (and, especially, easy to obtain for non-Bitcoin purposes). But that is not true of layer2 software – layer2 software can be part of a customized software-hardware pair (and, as a result, it can be outrageously more efficient).

See also:

- Peter Rizun demonstrates hardware scaling.

- Andrew Stone demonstrates software that handles 256 MB blocks.

See Appendix 2 for some of my ideas on what the next T.network might contain.

Finally: one last extremely intriguing benefit.

5. Security via Geographic Distribution

How well can the nations of the world coordinate? If two nations hate each other, then each country’s T.network can safely hide in the rival country’s jurisdiction.

A. Intro

To make the scheme effective it would be

important...to provide that banks in one

country be free to establish branches in

any of the others.

-F.A. Hayek, "Choice in Currency" (1976)

It's hard to imagine the Internet getting

segmented airtight. It would have to be a

country deliberately and totally cutting

itself off from the rest of the world.

Any node with access to both sides would

automatically flow the blockchain over...

It would only take one node to do it.

-Satoshi Nakamoto, "Re: Anonymity" (2010)

B. Round-Robin Political Asylum

T.Networks will be distributed geographically, for reasons of efficiency.

This distribution may trigger a marvelous and most unexpected benefit: round-robin political “asylum” for T.Networks.

Largeblock networks are more expensive to run, of course. But expense is not the primary drawback of Largeblock-ism. Instead, the concern with Largeblock-ism is that large nodes must send/receive/process a lot of data, and so it is therefore more difficult to conceal the node’s physical location. This, in turn, makes the node vulnerable to harassment and subordinate to the local politics.

For example:

Above: commentary “this is Bitcoin” from Samourai telegraph group. Bitcoin is anti-tyrant, pro-“protesters and dissidents”.

Now, consider what things would be like, in a Thunder-enabled Bitcoin world, when the Jurisdiction and Service Area don’t overlap.

The “people rising against police brutality in Nigeria” would use the “T.Africa” network – after all, they live in Africa. The Nigerian government is strong – perhaps strong enough to hunt down everyone running a full node in Nigeria. But what about the nodes in Cameroon? What about the nodes in Egypt? Or Morocco? Nigerian citizens can just start up a node located somewhere else, and VPN into it.

Law enforcement in Morocco is probably not going to give a ***t about why some crazy Nigerian dictator wants to halt some T.Africa payments. Would Egyptian police close down their own payments network to help foreign Nigerian police? I doubt it.

Politicians obsess about the political problems of their own country, but they care almost nothing about the political problems of their neighbors.

C. “Serves You Right!”

But it gets better! Can’t you imagine activists in the US and Europe running T.China and T.Asia nodes? They could not only run nodes, but they could run servers that quickly create more nodes. Perhaps these people are refugees who have recently escaped Russia/China; perhaps they are just political activists.

Plus there are always the foreign companies. Amazon Web Services can always sell (indirectly) T.China full nodes to people in China. They just need a VPN and some coins!

And, there are always the foreign governments. If there were just one Bitcoin network, then all tyrannical world governments might be naturally united against it; and so they would have an easier time cooperating to destroy it. But if there are many different networks that affect each country differently, some of the countries will be natural enemies of each other. The US government might run T.Asia nodes, purely to cause trouble for Vladimir Putin (or Communist China, etc). Maybe the Iranian government (always the victim of financial sanctions), would just run nodes of everything out of spite; or maybe the mayor’s office of London/NYC (financial capitals of the world) would run nodes of everything as a public service.

Above: The game Civilization IV; your government can adopt the “Emancipation” civic, to make life difficult for rival governments. If many rivals each adopt “Emancipation”, then you are basically forced to adopt it as well. From here.

D. In Summary

My point is: that the main drawback of a largeblock node, is its large computational overhead, and (therefore) greater vulnerability to the local government’s tyranny. An unexpected benefit of having a team of largeblock nodes –each serving a different region, but, via the internet, accessible from ANY region– is that the local government is effectively at war with node-wielding citizens in every jurisdiction.

( All the more so, with Drivechain’s Blind Merged Mining. In BMM, node operators “mine”, and earn profits with offset their node’s operating costs. In general, these equilibrium profits will fall to zero (even if there are merely two competitors, each trying to BMM). However, if nodes are subject to existential harassment, then the landscape would no longer be perfectly competitive. Some node operators would succumb to the existential harassment, but others would easily be able to ignore the harassment (giving them a comparative advantage, and profit opportunities). )

6. Adding It Up / Conclusion

A. How Many T.Networks Are Needed?

In Appendix 2, below, I estimate that a representative T.network txn could be shrunk to 197 bytes.

If all txns were 197 bytes, then 500 MB worth of blockspace could hold 2.538 million txns. At 1 block per 10 minutes, this would be 4230 transactions per second. Above, we calculated total worldwide TPS to be 35,000 in the year 2021. So, in other words, with just nine Thunder sidechains, Bitcoin could process every single transaction in the entire world, non-custodially.

B. What is the Cost per T.Network?

In Appendix 1, below, I estimate the cost of a 1 GB Thunder node to be $6825.50 upfront and $386.98/month.

Is this cost prohibitively high, or trivially low? That is best decided by you, the reader.

It is about as much as Americans spend on their cars – a couple thousand down and then a couple hundred a month.

Certainly it is small compared to running an exchange, a mining operation, hiring a software developer, or purchasing 2 BTC (aka 1-millionth of the total supply). It is small compared to the USD status quo, as currently we have no way of “running a full USD node” (so, there, the cost is infinite). On the other hand, for a hobbyist it is very high.

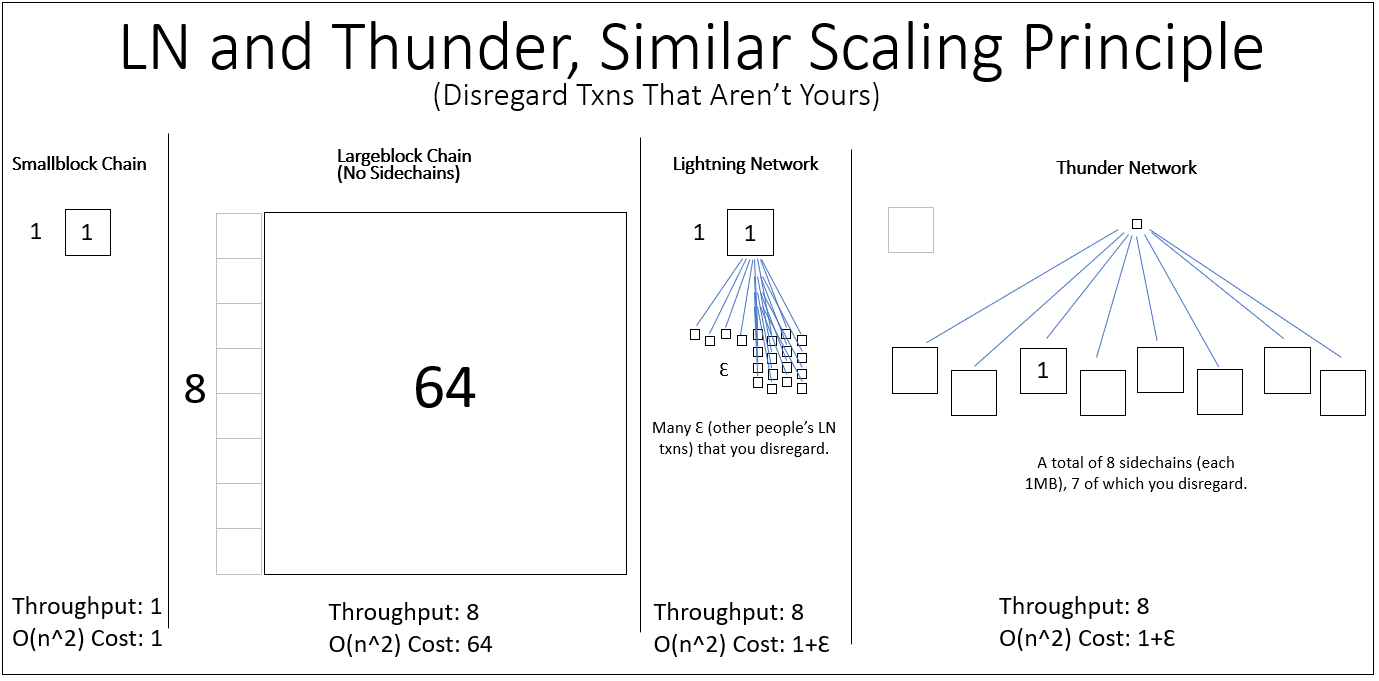

C. Why not consider the total cost?

The total cost, for nine T.networks, would of course be $61,429 upfront and $3482 per month.

But each user only needs to validate their own payments (and, in particular, only those payments in which they receive money). Similar to the lightning network, users can safely disregard txns that don’t apply to them.

And users can insist on getting paid on their own network. In that way, they should only ever have to validate one T.network.

Appendix 1: USD Cost of 1 GB Blocksize Node

Let us go through the requirements.

Note: I looked these prices up in mid-2020 and it of course likely that they will change over time. But I have included exactly the hyperlinks that I used in mid-2020, anyway. Hopefully they will remain accurate for a while.

A. Storage

I’ve previously mentioned that sidechains can (unlike the mainchain) discard old history. With clever UTXO commitments, it may be possible to discard block history older than 6 months.

Since there are 26,280 blocks per 6 month period, a 1 GB blocksize would yield total storage requirements of 26.28 terabytes for block data, plus more to store UTXO data and other databases.

- $3,000 for the hard drive

B. Bandwidth

1 GB per ten minutes, is 8000 bits / 600 seconds, which comes to 13.33 Mbps. Our requirements will be greater – we must account for variability in inter-block times, and precious upstream bandwidth.

- This Verizon Fios 1 Gbps service charges $215/month

C. Computation

A typical 1 MB block will contain about 2,500 txns. So we can expect a 1 GB block to contain 2.5 million txns.

Jameson Lopp has tested node performance and found a machine that could sync Bitcoin Core from genesis (Jan 3, 2009 - Oct 23, 2018) chain in 311 minutes. Most interestingly (for our purposes), the machine was apparently CPU-bottlenecked.

Blockchain.info reports a total of 350,934,692 txns during this (Jan 3, 2009 - Oct 23, 2018) period.

Thus: 350,934,692 txns / 311 minutes = 11,284,073.7 txns per 10 minute period. Again, inter-block times vary tremendously, so we need to be able to deal with occasional “bad luck”, but this machine’s CPU can do 4.514x our baseline requirement (of 2.5 million txns per 10 minutes).

- I could build a machine with twice as much RAM (as Jameson’s), and 15% more CPU speed, for $3205.24.

D. Electrical Power

The computer’s power supply is rated at 1200W (ie, 1.2kW). If we somehow required 100% of this power, 24/7, then 24 hours in a day, we would consume 28.8 kWh. At $0.1320 / kWh, this makes 3.8 $/day, or $114 / month.

If we add 20% it should be more than enough to cover the CPU and the huge Hard Drive Array.

- So, $ 136.8 / month.

E. Total

If we add a 10% “fudge factor” (for installation, labor, unexpected items, etc), then we have:

- $ 6825.50 upfront

- $ 386.98 / month

The true total cost of ownership is almost certainly lower, since we overestimated everything.

Appendix 2: Possibilities for the Next T.Network

A. Schnorr / BLS

Can add Schnorr signatures natively (ie, make it so that all outputs are Taproot-Script).

Or perhaps: BLS-signatures

B. Smaller Txns

If the sidechain is going to emphasize scalability, then we might try to make txns as small as possible.

Satoshi’s txns actually have a bit of waste in them:

- There are four “version bytes”, which allows for billions of possible txn versions. Yet, of these billions, we only use three. Thus we can cut these four bytes down to one, saving three bytes.

- The nLockTime field is often not used. Yet it consumes four bytes. We could specify that its presence or absence depends on a specific “version” value. Thus saving four bytes in most cases.

- Most transactions take in 5 or fewer inputs and pay out to 5 or fewer outputs. Yet two bytes are used to specify the in/out information. We could pre-define some version-types to always describe a txn that takes these “vanilla” forms (1 input 2 output P2PKH, for example). Thus we could elimiate the interior VarInts, or even elimiate the interior Scripts.

If Thunder is going to specialize in on-chain txns, it doesn’t need any features at all. Just the bare minimum for sending a txn will do.

For example, a “minimal” txn might look as follows:

1 byte: version*

36 bytes: Input UTXO: TxID (32 bytes) + Position (4 bytes)

104 bytes: spend authorization

71 bytes: signature**

33 bytes: Compressed PubKey

28 bytes: output 1 -- value (8 bytes), Hash160 (20 bytes)

28 bytes: output 2 -- value (8 bytes), Hash160 (20 bytes)

See (*) and (**), below.

…for a total of 197 bytes.

(A pretty decent savings, considering that in Bitcoin Core this txn would require 222 bytes.)

* Version will specify # of inputs and outputs, in this case: (1, 2). With 100 of the (now) 256 version types, we can specify txns containing anywhere from 1-10 inputs and 1-10 outputs.

** See here and here, these are now always 71 bytes or fewer. [If fewer, can pad with zeros and have the interpreter redo it if fail AND zero-in-padding-location.]

C. Other Opportunities

- Currently, including “memos” via OP Return requires that there be a 0-valued output (ie, 8 bytes that consist only of zeroes). Instead pre-define some version type as one which always contains a “memo” field in a certain location. This would save those 8 bytes from being wasted.

- When new features are added to Bitcoin Core as “soft forks”, they tend to involve awkward flags or indicator bytes. But when the next Thunder network is ready to be created, these features can just be folded into a new txn version, thus costing zero marginal bytes (and involving no awkwardness).

D. Accumulators / Fraud Proofs

Not only can we save on bytes, we can also increase the security of SPV. One big way, would be to eliminate Class-4 block-flaws via accumulators, as I describe here. This would allow Bitcoin to support Fraud Proofs. SPV nodes could be warned –cheaply, reliably, and instantly– if any block is invalid in any way. Thus, SPV-nodes would have the same security as full nodes3. This is ideal, because (of course) on a largeblock system, most users will run SPV nodes.

E. Simple Malleability Fix

The “SegWit” method used by Bitcoin Core to fix transaction malleability is (unfortunately) very bizarre and complicated. Instead, a “hard fork” method of just editing the transaction serialization function would be much much clearer.

F. Other

From the hard fork wishlist:

- Byte order consistency (big endian)

- Eliminate redundancies in the variable length integer encodings, possibly switch to a standard.

Footnotes

-

In fact, since Lightning requires layer-1 bytes to onboard each new user, and requires period layer-1 bytes for maintenance, it is only barely a “layer 2” in the scalability sense. ( The chief advantage of LN is not scalability at all, but instead instant trustless payments, that can take place without the mining process or the rest of the Bitcoin network. ) ↩

-

That seems like a believable number. There were 7.42 billion people in 2016, and only ~65% are adult. ~2B still live in extreme poverty, and many live in unbanked developing nations. ↩

-

This is not to say that the network as a whole can now rely only on SPV nodes (which is an error often articulated by LargeBlockers, especially BSV-ers). There is no getting around the Data Availability Problem: someone has to “host” the blockchain’s data …we can’t all get it from someone else! (This is also why SNARKS are inferior, as a scaling solution – they are basically just opaque Fraud Proofs.) ↩