Consent of the Governed -- Appendix

Paul Sztorc

21 June 2019

Appendix: Rights

This was originally Part 3, Section D. But it isn’t relevant to the conclusion, so I moved it here.

i. Laws vs Rights

Just as laws “advise” people on how to behave, Rights “advise” laws on what they should say.

Whereas Laws are specific, concrete, numerous, contain exceptions, and are occasionally revised or removed, Rights are general, abstract, few in number, contain very few exceptions, and are almost never revised or removed.

In this sense, Rights are a kind of Platonic Ideal toward which the individual imperfect Laws strive. We can evaluate a portfolio of laws, based on how well they serve a set of Rights.

ii. From where do we get our rights?

The opening quotation of this essay claimed that it was “self-evident” that men were endowed with “unalienable Rights” to Life and Liberty. But this cannot be literally true. Since the document’s publication in 1776, nearly all the Americans living under its protection have died (against their will), at some point or another. So the Right to Life was de facto alienable. Worse, the quotation says that rights came from “[our] Creator” – first introducing theology into the equation, but second implying that if Creator changed His mind, we would then lose all of our rights. And that doesn’t seem to make any sense either. So we cannot take the Declaration’s advice in this case.

Some people feel that Rights need to be “derived from” something. But this also doesn’t seem to be true. The things we build, are constructed using tools and ingredients that almost never resemble the final product. And the things we want certainly don’t seem to be “derived from” anything nearby (people just ‘get hungry’, whether they think about it or not) – and if someone wanted to want something new (ie, a want not derived from a previous want), it isn’t clear why this should be ‘prohibited’ (or whatever).

iii. Rights are Objective Norms

In my view, Rights (the real ones that we actually get in reality) are just objective norms. They are behavioral guidelines that are near-universally endorsed. When a group of people is pretty sure that they all want the group to behave a certain way, then you have a Right. This is why Rights need to be simple, uncontroversial, few in number, containing few exceptions, etc.

It is also why it is strategically advantageous to say that a hypothetical new Right has been “derived from” something that’s already popular and well-known (such as God), even if in fact it wasn’t – the supporters of the new Right won’t care enough to even look into it in the first place, and the detractors will be hung up on trying to refute the derivation (and since all refutations are arguments, the supporters can just pretend that they weren’t convinced – so it costs them nothing).

Since Rights should apply universally (independently of a person’s individual situation), we should be able to discover them over time, the same way we discover the laws of physics. We should also be able to discover faster ways of discovering the best Rights.

iv. “Negative” Rights / Skyhook Governance

Anarchists attempt to take refuge in the so-called “negative rights”, such as freedom of speech. Supposedly, no one needs to do anything in order to provide these rights. And so any government –even no government– could supply negative-rights to the people in unlimited quantities. They could do so by simply doing nothing.

It is true that [Laws defending] these Rights are cheaper to [enforce], and their efficiency deserves our respect. But, unfortunately, such Law-enforcement is not free, either. Most fundamentally, the Rights are lost if a neighboring (or internal) tyrant finds it advantageous to invade, and loot the country in a Right-violating way.

If you endorsed the “non-aggression principle”, for example, you would be unable to invade your neighbor’s property – but your neighbor would still be able to invade your property! NAP-advocates assume that they can choose rules for themselves (constraining their own behavior), and also for other people, against their will! But this just assumes away the problem of governance – as if a rocket scientist assumed away the problem of escape velocity.

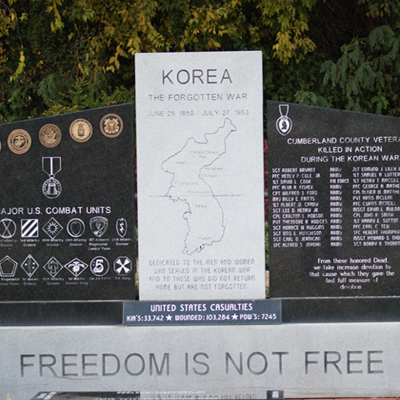

For citizens to retain a set of Rights, they must retain a corresponding set of Laws – no tyrannical Laws can be added, and no protective Laws can be removed. Thus, to retain a set of Rights, the sovereign (whoever that is) must remain in power. “Freedom isn’t free”, as the saying goes. (But, through innovation, we can make it cheaper over time.)

Above: Cumberland Country Korean War Memorial, with popular American phrase “freedom isn’t free”. From here.

See also:

- Map of Invasions in Europe From Pinterest.

- “Anomie” – If you want to change society’s values, you need to make sure that you have a way of installing those values into other people. (You can’t just “declare the NAP” for everyone).