A MAHF should shun replay protection, and instead try to replay everything. With >51% hashrate, this is easy to do. Miners can defeat full nodes, and upgrade the network via Hard Fork, if and only if investors are on their side. Miners’ expected profits are maximized if they follow the advice of futures markets as a source of robust, decentralized, and accurate advice.

Motivation

This is about the MAHF. I don’t really like hard forks, because they necessarily involve the destruction of the existing network. I prefer sidechains, which let us…tener los dos, as they say.

Nonetheless the MAHF has got a lot of discussion lately, and I again find myself in disagreement with almost everything that everyone else is saying. The MAHF interacts with another issue, called “replay protection”, that is also popular these days, and that I also disagree with.

Replay Protection

People won’t stop talking about this concept. On Twitter alone, by my last search, it has been mentioned at least 2,300 times:

And I clicked through 7 or 8 pages at random – they were all 100% Bitcoin related. Check for yourself if you want!

Background

As you know, two “spinoffs” (altcoins that preserve Bitcoin’s ownership) are currently the talk-of-the-town: “SegWit2x” and “Bitcoin Cash”. If one of these were to replace Bitcoin today (ie, if old Bitcoin dies), then it would be the first hard fork upgrade of Bitcoin (depending on how one accounts for the March 2013 consensus-failure and the later bugfix).

A cadre of Core Developers pushed aggressively (and successfully) for Bitcoin Cash to add replay protection, insinuating that failure to do so carelessly introduces “risks”, and that the only “ethical” thing to do is not only to write replay protection, but to make it mandatory.

And while the late steamer Big Missouri worked and sweated in the sun, the

retired artist sat on a barrel in the shade close by, dangled his legs,

munched his apple, and planned the slaughter of more innocents.

-- "Tom Sawyer" (1876), by Mark Twain

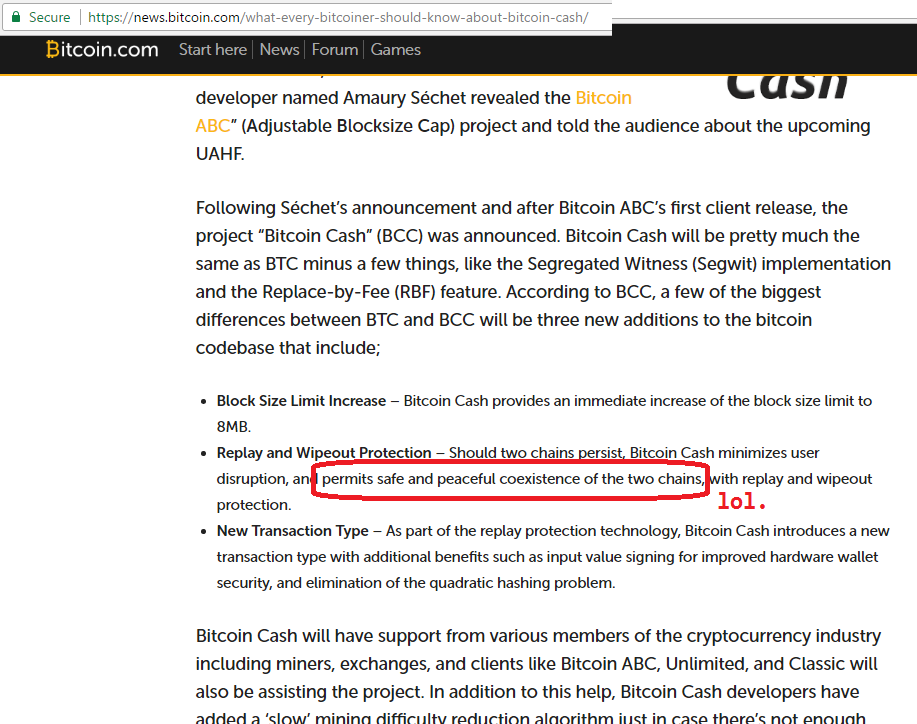

To my great personal amusement, this campaign succeeded. As you can see below, Bitcoin Cash proudly touts its new replay-compliant technology:

I won’t speak to the “ethics” of replay protection, only its efficaciousness at accomplishing certain goals on the “macro” chain-level.

What is Replay? Replay Protection?

Here is a great StackOverflow answer:

... transaction replay is when a transaction is valid on both sides of the

fork. ... if you intend on sending coins on one fork, you could accidentally

end up sending your coins on the other fork as well ...

That’s all it is.

Replay protection is something that makes it so that transactions on one

chain are invalid on the other chain thus preventing transaction replay. ...

And that’s all that is.

Here’s an Ethereum-focused, DAO-related answer for “What is a replay attack?”. It is important because Ethereum kicked off the replay party with their unintentional chain split, following the DAO failure last year:

[In] blockchains...taking a transaction on one blockchain, and maliciously

or fraudulently repeating it on another blockchain.

While the concept is simple, it can be handled in a few different ways.

Types of Replay Protection

Three Basics

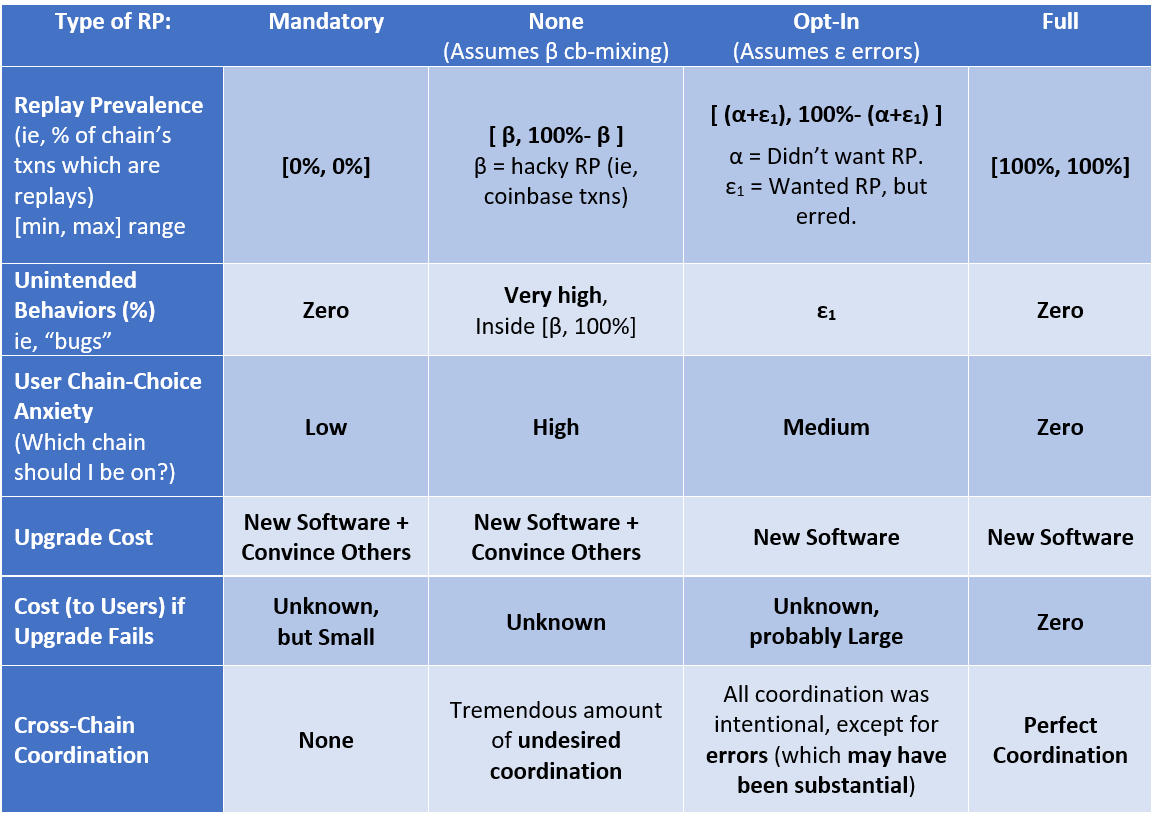

Which chains, if any, should a given txn be valid on? There appear to be four major approaches. The first three are well known:

- “No RP” – The most permissive extreme. The New Chain declines to do anything – txns will be replayed, at will.

- “Bilateral Mandatory RP” – The most restrictive extreme. The New Chain forces users to create ‘new style’ txns that are not replayable on the old network, it simultaneously declines to accept any ‘old style’ txns – this guarantees that the New Chain will be a spinoff or altcoin, and not a HF.

- “Opt-In RP” – The New Chain can give users the option of creating ‘new’ or ‘old’ style txns. The new network will accept both txn-styles. Users can choose, per txn, to split their money or to keep the blockchains synchronized.

Full Replay

However, I believe that there is a fourth way, in which a hashrate majority aggressively implements replay as a feature.

In fact, with a hashrate majority, the New Chain should be able to replay everything happening on the Old Chain. This is because a hashrate majority will always have greater blockspace in a given amount of time (say, one day). (The only exception is an obscure case where the New Chain’s blocksize is substantially smaller than that of the Old Chain’s – a feat which a hashrate-majority could accomplish with a mere MASF.)

Firstly, the Old Chain cannot “hide” txns from the New Chain, because the Old Chain is public (by definition).

Secondly, the New Chain can be created with rules that force all replayed txns to always be valid. For example, the New Chain might have two “zones” of txn: Zone 1, which is full of replayed transactions only, and Zone 2, which contains normal transactions. NewChain might then have a rule as follows: txns which travel “from Zone 1 to Zone 1” are not even checked for validity at all. They are “anyone-can-spend”, until someone makes a NewChain txn selecting them. A NewChain message takes the txn “from Zone 1 to Zone 2”, at which point it stops being “anyone-can-spend”. In such a case, any replay protection on the Old Chain is always defeated – it is impossible for [non-miner] users to create anything that is valid only on the Old Chain.

Thus, it is always possible for a NewChain to defeat all forms of replay protection (ie, possible to replay each and every OldChain txn).

What if it is an actual rule on the NewChain, that it must contain each and every known OldChain txn? NewChain nodes could contain an OldChain node (temporarily), and when OldChain blocks have 6 confirmations, the NewChain rule could be that all of these txns be included in “Zone1” of the NewChain.

This results in a qualitatively new phenomenon that I call “full replay”.

The table above places each approach in its own column. The epsilon_1 value represents the people who don’t currently know what replay protection is, but will wish that they knew what it was in the immediate future.

Is Replay Good or Bad?

Well, it depends.

Replay is bad when one wants to make an Altcoin, or a spinoff. In these cases, someone is trying to make a separate network, and doesn’t want this network to be harassed by irrelevant messages. In these cases, replay protection is essential.

But the story is quite the reverse when one is attempting a MAHF. In these cases, the goal is to try to move an existing network, and avoid splitting the networks as much as possible. In these cases replay is desirable. In fact, any given soft fork upgrade is basically in a constant state of being full-replayed on all of its predecessor protocols.

( I find that the “compromise” strategies (“None” and “Opt-In”), to indeed be mere errors. )

The MAHF

This section is about a Hard Fork upgrade to the Bitcoin protocol, that is initiated and controlled by Miners.

Background: The “Evil Fork”

Today, it is known that a majority hashrate can already force a “hard-fork”-like upgrade, using the so-called “evil fork”.

All Hard Forks are “Evil Forks”

And, furthermore, as an (often overlooked) matter of terminology, every hard fork must be forced, because (at least by my definitions) if it leaves the old network alive it is a spinoff or altcoin.

In every hard fork, the old chain no longer exists, because a critical mass of support has abandoned it. We might specify an ‘evil hard fork’ as one where the abandonment is done exclusively by miners. And empirically, we might try to measure ‘evilness’ by tracking tx-volumes before and after the fork. But perhaps users want the tx-volumes to go down (just as nodes are today protected by the infamous blocksize limit)?

We will talk about “measuring what users want” at the end of this section, because it is important and there is a way. Here, I just want to point out that labeling the fork “evil” is somewhat misleading. For better or for worse, every Hard Fork is an evil fork – no spinoff can be considered to be a hard fork, unless it smothers the old chain to death somehow.

This design-consideration is tacitly-acknowledged in the hard fork proposal called “ForceNet” by Dr Johnson Lau. Furthermore, as I stated, it is one of the implicit goals of the soft fork – to maintain consensus, in this case by preventing rival chains from being born (in contrast to the hard fork, which actively kills previously-alive chains). And it is also, ironically, one of the goals of mandatory replay protection – that users always control 100% of their value on all chains. After all, the only difference between “a hard fork in order to please everyone, keeping everything on one chain” and “spinoff altcoin so that people can go their separate ways, including mandatory replay protection” is that there is one chain instead of two.

Is “Force” Always Anti-User?

I think that the following are undisputed: The user is king. This is because people can freely install/delete whichever software they like. And, therefore, we will eventually converge to a world where all of the software that exists, is also the software that is most-effectively serving the user. Therefore, we should take a shortcut and try, upfront, to design software only the software that best meets the needs of users.

However, does “user is king” always imply that we should never “force” the user to do something?

When I travel, I am free to fly on any airline I wish, or on no airlines. But, when actually on the airplane, I am often “forced” to sit down and/or buckle my seatbelt, I am not allowed to cause too much noise or distraction, I am unable to leave the plane (most times), and I really have no control over where the plane is going, when (or even “if”) it takes off or lands.

Furthermore in game theory there is a well-known Paradox of Control – the more control you have, the worse-off you often are. For example, if want to ask your boss for a 10% raise, it benefits him to be magically “unable” to discuss raises with you, or to be magically unable to give you more than 2%. The most-effective negotiator is the one who can say “Sorry pal, I don’t make the rules”.

When coordination is involved, arbitrary leadership can be important. Tom Schelling gives the example of cars stuck in gridlock – if one individual driver arbitrarily begins to issue directions to the other drivers, and if these commands are obeyed, then everyone may benefit, even the driver who is liberated from the jam last. Instead, if everyone tries to do the yelling, or if no one obeys, then they are all comically trapped forever.

Such ‘coordination problems’ are very common when there is a first-mover disadvantage. For example, imagine that everyone would like to overthrow the government, but the first people who try to do so bear a great risk (of being executed for treason). Or everyone (or some arbitrary super-majority) at a party would prefer to move to a different room, but no one wants to be the first person to do so (as they risk looking foolish).

So it seems that, often, people will opt-in to having force imposed on themselves. In fact, how else would you describe the act of signing a contract? It is really allowing Present-You to direct the courts (or whoever has sovereignty) to “force” Future-You to do something.

In fact, it is because users can choose to run (or ignore) any software they want, that I conclude that anything the software is able to do, is ‘fair game’ – it was implicitly endorsed by the user upon installation. No one is “forcing” you to use Bitcoin.

The MAHF I will describe, may, in fact, be the only way to Hard Fork that does not involve the risk of a network split or the risk of users losing funds. So, if the MAHF is your goal, this is probably the safest way to do it!

( Although, again, if you don’t like the idea of miners MAHFing your, or developers ForceNetting you, then you may enjoy the concept of Sidechains, which allow users to freely go on whichever inter-operable chain they like. )

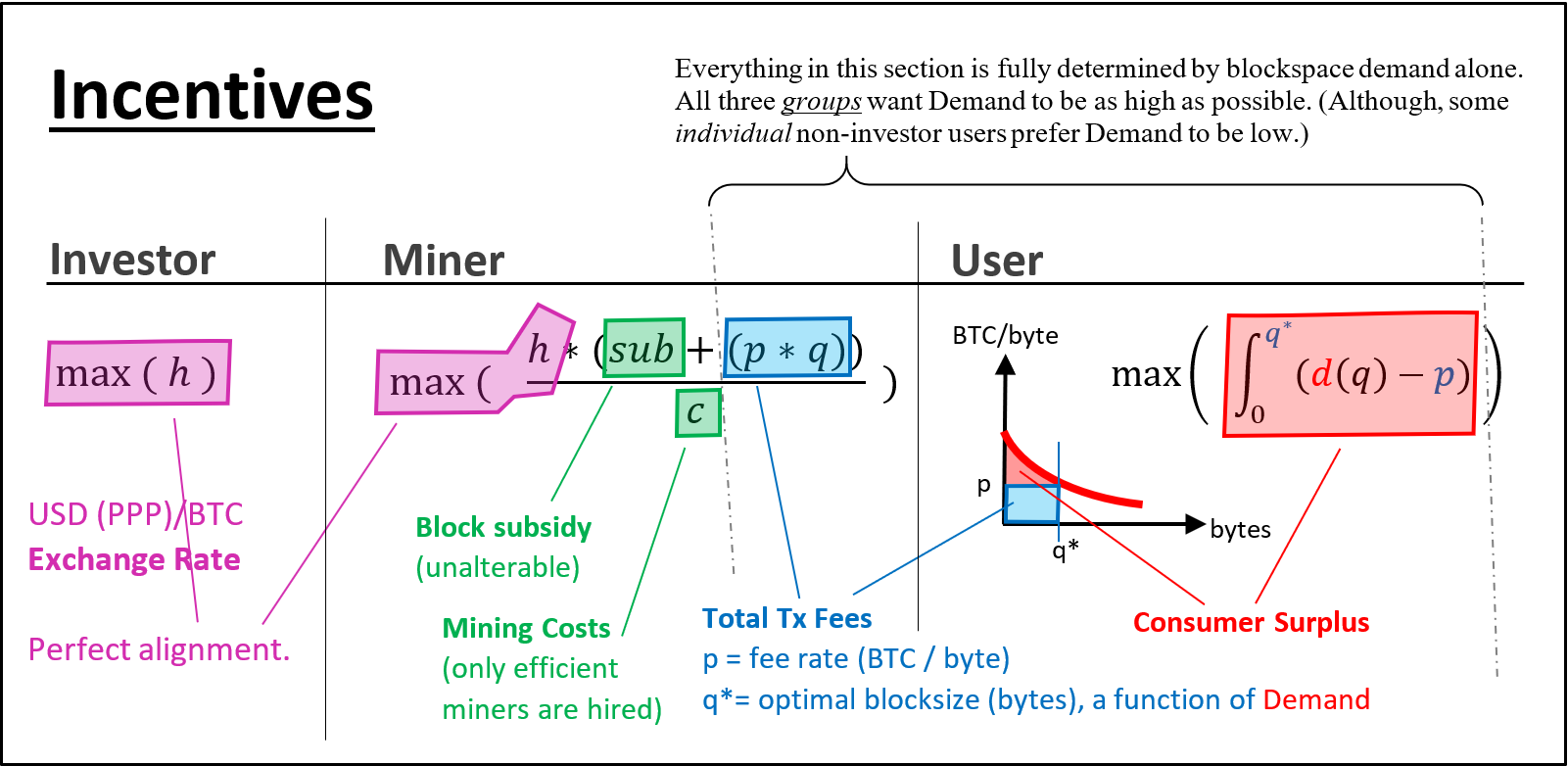

Miners = Users

Finally, you should know that I believe that the interests of miners must always align with the interests of users. This is because, as I will explain later, miners are required to make an earnest attempt to meet the needs of Bitcoin investors and users. They must do this, because [1] miner-revenues are a direct function of both the Bitcoin exchange rate and aggregate transaction fees, and [2] mining has no barriers to entry, is extremely competitive, and the difficulty adjustments happen very frequently. Therefore, if the interests of miners are not aligned with those of investors, this can only be because miners attempted to measure the investor’s desires and made an honest mistake.

So, in practice, there are no ‘evil’ hard forks. There are just well-designed hard forks that are likely to succeed. And there are Hard Forks that maximize user happiness, and those that minimize user-inconvenience. And there are badly-designed hard forks, those which fail to acknowledge the game-theoretic nature of the coordination problem (or, more likely, hard forks designed by people who have given zero thought whatsoever to hard forking).

With that attiude in mind, I will now set out to improve the Evil Fork.

Flaws in Evil Fork 1.0

The existing ‘Evil Fork’ design (“EF1”) has some serious impracticalities:

- It Sounds-the-Alarm as loudly as possible – when the Evil Fork 1.0 is used, it presents us all with undeniable, un-ignorable evidence of malfeasance. This is disadvantageous because it makes it very easy for users to mount a coordinated resistance, as most of the work involved –gathering everyone together and persuading them of the problem and of their individual need to act– has already been done by the clumsy miners.

- During the transition period, there is a kind of ‘unproductive stalemate’ where no one can do anything – users can’t transact, and miners can’t collect txn fees. Obviously this is very costly with no clear benefit. But it is also ineffective strategically. While miners will try to persuade users otherwise, this mutual headache can be most-easily attributed to the miners, as they are the ones who initiated the disequilibrium. Thus, while in the EF1 miners will be hoping that users will voluntarily surrender, the reverse is more likely.

Instead, I propose a new MAHF, the “Evil Fork 2.0” (“EF2”). It uses the same resources (majority hashrate) as before, and it accomplishes the same goal (triggering a MAHF). But it also:

- Doesn’t force miners to risk earning less money, and in fact allows them earn strictly more money.

- Does not inconvenience users, and “persuades” them to change forks in a gentler, less-immediate way.

The Evil Fork 2.0

Here, I propose the “EF2”, a way for >50% hashrate to upgrade the network via Miner-Activated Hard Fork (MAHF).

If >50% hashrate runs “EF2 software” for a period of 0-4 weeks, then the following interesting things are true:

- The hard fork must succeed (the NewChain will always come to life and the OldChain will always eventually die),

- users are forced either to use both the Old and New chains, or to permanently defect to the NewChain; replay protection is impossible,

- users can take as long as they like to switch from OldChain to NewChain (even forever),

- it is impossible to make an enforceable commitment to remain on the OldChain; a user who “is committing to remain on the OldChain no matter what” is equal in every way to one who “plans to switch tomorrow”,

- participating miners actually earn more BTC than they otherwise would; this is through more mathematically-higher tx-fees, and a one-time difficulty reduction,

- non-participating miners cannot find a valid OldChain block, until they capitulate to the hard fork.

The EF2 is automatic (ie, “decentralized”, and not requiring any decision-marker or decision-making) and incentive-compatible.

Overview and Assumptions

EEE and The Krawisz Special

This MAHF uses a strategy similar to Microsoft’s “embrace-extend-extinguish”. It first mimics the Old Chain as much as possible [“embracing”]; second, it does a little extra [“extending”], and finally, it makes life intolerable for users and miners on the Old Chain [“extinguishing”].

It also has the feature that it –ultimately– gives miners very strong incentives to measure investor’s preferences with prediction markets. So we might instead call it “The Krawisz Special”.

But I will henceforth refer to it as “EF2”. But, as I mentioned above, calling it “evil” is a little unfair – it is actually the only safe way to accomplish a MAHF.

Assumptions

The EF2 requires:

- A hashrate majority.

- A small amount of miner-to-miner communication.

- That Miners NOT use this MAHF to shrink the max blocksize limit by a large factor. (But they can instead increase it, keep it the same, or shrink it moderately.)

Finally, the EF2 is free, and doesn’t cost the miners anything (nor force them to risk anything)…if a fourth condition is met:

- The end-user is indifferent between using the New chain and the Old chain.

The fourth assumption is quite important, and worth discussing quickly.

Who Cares About These Forks?

Let me first clarify that my description of “EF2” is limited to the activation technique (for a given upgrade). The EF2 is not interested in the upgrade itself (nor its features, endorsements, etc).

However, this is not to dismiss the topic! The content of the upgrade is of tremendous relevance! If the user really did prefer one chain to the other, then in the long run nothing else would really matter. (Hence, the EF2 is really a way for miners and users to more-easily enforce an upgrade together.)

Now, some end-users won’t care about the EF2 at all:

- BTC-Spenders – Those who use Bitcoin to make USD-denominated payments. These users don’t care what they’re using, as long as it works.

- Long-Term Hodlers – Pre-HF hodlers are perfectly hedged among the two monetary units. They will have no reason to care about the debate at all, and especially no reason to decide to care (as this would entaile pouring resources into research and code review).

Speculators, however, will care about the HF. They will assess, and care about, differences among the forks, and they will care enough to make trades, and thereby to set the exchange rate of each BTC-type. I will talk much more about this later.

The Other Assumptions

While Assumption #4 is quite important, the first three are trivial by comparison. For example, they are all present in the SegWit2x MASF, for example, which asserts 83+% hashrate support, and intensive inter-miner communication.

EF2 Specification

1. Goal and Strategy

The EF2 achieves a MAHF by focusing on two goals: first, it tries to decrease the hashrate on the Old Chain to zero; second, it tries to persuade users to willingly switch networks (from Old to New).

The first goal is accomplished through aggressive (and intentional) orphaning on the Old Chain; this eventually persuades 100% of the hashrate to abandon Old for New. Those who trigger the orphaning (the “Strike Team”, below) are compensated with funds from both chains, so they bear no risk of the MAHF failing. Attempts to restart the Old Chain will always fail, unless the PoW-algo is changed (at which point it becomes a UAHF, and one that is about something else).

The second goal is accomplished by keeping the user indifferent between the two chains. The user can wait as long as he or she likes (even forever) before switching from Old to New, but the user cannot as-easily switch backwards from New to Old. The Old Chain becomes more and more difficult and expensive to use, and it eventually stops working altogether. But the user’s money is still there (on both chains).

2. Details

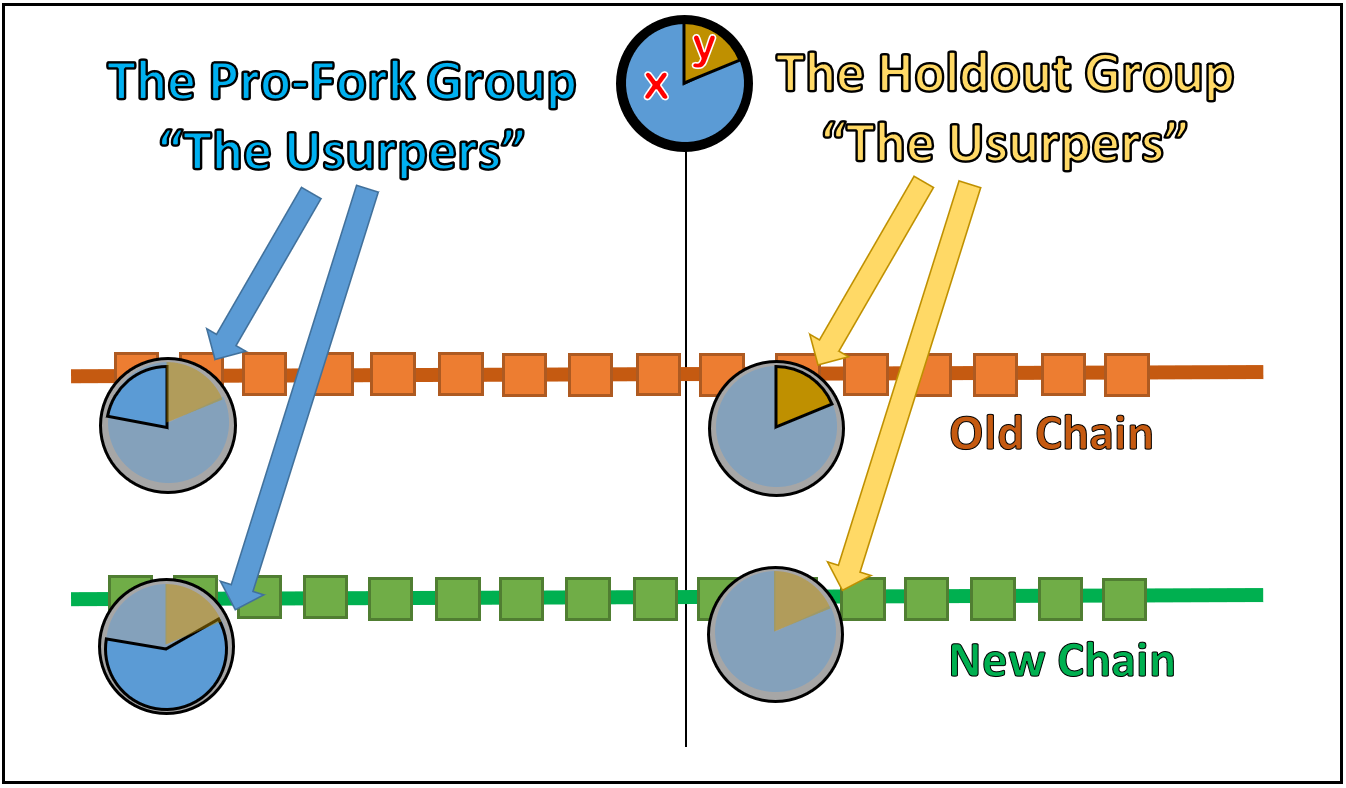

Define the MAHFers as the “Usurpers”, and define any miners who are opposed to the MAHF as the “Loyalists”. Some of the Usurpsers will form a second team called the “Strike Team”. And some (eventually all) of the Loyalists will surrender and join the loyalist team, becoming “Defectors”.

Define x as the hashrate (%) of the Usurpers, and y=(1-x) as the hashrate of the loyalists. And use it in the following way:

- Devote (y*(1+e)) of the Usurper hashrate to a ‘Strike Team’ that mines the Old Chain (e = “a trivial amount”), with the goal of disrupting the Loyalists.

- Mine the New Chain with all remaining Usurper hashpower, such that blocks are found approximately every 10 minutes. To do this, the MAHFers will have to manually reduce the difficulty of the New Chain (as part of the EF2 hard fork event that initiates this entire process).

- On the Old Chain, the Strike Team 51%-attacks the Loyalists. Specifically, the Strike Team aims to henceforth win every block (of the heaviest valid chain)”. The Strikers change the tx-inclusion policy as little as possible – ideally, not at all.

- On the New Chain, the Usurpers initiate a “full replay” (described above) of all the txns on the Old Chain. Moreover, they include additional txns when possible (ie, Zone 1 to Zone 2 ; and 2 to 2). Notice: these New-only txns can not be replayed on the Old Chain.

- Loyalist miners will, at this point, be mining…but never finding any blocks. They will therefore be constantly losing all of their money. Some of them will become “Defectors” and defect to the New Chain.

- [Optional, depends on initial x and y values] As more Loyalists defect, the difficulty of the New Chain will adjust upward. As the difficulty adjusts upward, estimate the hashpower remaining on the Loyalist side, and “call back” some members of the strike team.

- Repeat until x=100% and y=0%.

By far, this MAHF is easiest when the Loyalists have less than (1/3) of the global hashrate. In this case, step 6 is optional [and the technique is much easier to explain].

Since the SegWit2x NYA supposedly has about 85% of the network hashrate, those are the numbers [and explanation] I will use in the example below.

3. Example

First, let us set up the problem. If the Loyalists have 15% hashrate, we may choose epsilon of (.33), leading to a Strike Team of 20% hashrate. This leaves 65% hashrate for the Usurpers [85% - 20%]. By definition, no one has defected yet.

To achieve a 10 minute inter-block time on the New Chain, its difficulty is scaled down to match the hashrate on it.

Old Chain | New Chain

"Loyalists" "Strike Team" | "Usurpers" "Defectors"

15% 20% (sum=35%) | (65%) (0%)

|

| (new_difficulty = 65% old_difficulty)

Now the Usurpers will track whose blocks are found by whom. This monitoring requires some amount of trust on the part of the MAHFers, as there is slight statistical ambiguity for the Strike Team in the short run – are they unlucky, or slacking off, or are they pretending to be Defectors? I will talk more about addressing this later.

Below is a table where each line represents a 2-week period. The entries in the cells represent the number of blocks found by each group. I have expanded the rows to add some annotations.

If you find this confusing, look at the “BiWeekly Period” column, and restrict your attention to the rows that are numbered.

Summary of Probable Events:

- First period, the EF2 begins. The Usurpers reduce difficulty by a factor of 0.65, and so they find all 2016 blocks with their 65% hashrate. Difficulty on the New Chain, therefore, does not change.

What is their opportunity cost of doing this? If instead they had mined the Old Chain, they could have found 1310 regular Old Chain blocks. Furthermore, as we will see, they must pay the Strike Team for the blocks which they have found (which will be 400). They find a surplus 306 blocks [=2016-1310-400].

On the Old Chain, the Loyalists find 300 blocks, but these are orphaned by the 400 blocks found by the Strike Team. The Old Chain finds 400 blocks total, but the difficulty does not fall, because the current adjustment cycle [of 2016 blocks] has not yet finished.

- In the second period, two weeks have passed, and one third of the Loyalists (5% of the total hashrate) have realized that they are making no money; and these defect to the New Chain. The only effect this has, is that (next period) the New Chain difficulty will increase by about 7.6% [ which = (70%/65%) = (2170/2016) ].

- On week five, the Usurpers don’t find all 2016 blocks, now that the New Chain difficulty has adjusted. However, they can still afford to pay the Strike Team and have a surplus of 163 blocks.

- By week seven, all of the Loyalists have surrendered. They mine on the New Chain where they are not orphaned.

- This row describes the last phase, in which the Strike Team is maintained even though it is completely unopposed. While expensive, it is still mostly [301/400] achievable, because the difficult on the New Chain is still relatively low.

However, the Usurpers will need to “call back” (transfer from Old to New) the hashrate that would have mined 99 Strike Team blocks. This sets off a process which eventually destroys the Strike Team: the NewChain difficulty to increases further, which calls back more Strikers, etc.

Diagram:

BiWeekly == Old Chain == === New Chain ===

Period "Loyalists" | "Strike T" || "Usurpers" | "Defectors"

(15%) | (20%) || (65%) |

-------------------------|--------------||-------------------|-----------------------

| || |

1 300 Blocks | 400 Blocks || 2016 Blocks | 0 Blocks

| || - 400 reimburse |

| || -1310 expected |

| new: 400 || =306 surplus | total: 2016

| total: 400 || 306 | next_diff: 0

-------------------------|--------------||-------------------|------------------------

[-100] | || | [+154] [=100*(1/.65)]

2 200 Blocks | 400 || 2016 | 154

| || - 400 |

| +400 || -1310 +306 | 2170

| 800 || 612 | 154

-------------------------|--------------||-------------------|-----------------------

| || |

3 200 | 400 || 1873 | 140

| || - 400 |

| +400 || -1310 +163 | 2016

| 1200 || 775 | 154

-------------------------|--------------||-------------------|-----------------------

[-200] | || | [+331] [=200*(1/.65)*(1.076/1)]

4 0 | 400 || 1873 | 471

| || - 400 |

| +400 || -1310 +163 | 2344 [=1873+471]

| 1600 || 938 | 482

-------------------------|--------------||-------------------|-----------------------

| || |

5 0 | 301* || 1611 | 405

| || - 301* [max] |

| +301 || -1310 + 0 | 2016

| 1901 || 938 | 482

-------------------------|--------------||-------------------|-----------------------

In week 5, the Strike Team rejoins the Usurpers on the New Chain.

4. Dynamic Strike Team

In this example, the strike team mostly remained where it was. This was merely because I did not want to over-complicate the example. In reality, as Defectors abandoned the Old Chain for the New Chain, some of the Strike Team could follow them back. As more non-Usurper blocks are found on the New Chain, the total amount of reward available to pay the strike team (ie, the number of ‘reimbursed blocks’) should also fall.

However, care must be taken to avoid withdrawing the Strike Team too quickly. A simple technique for ensuring that the Strike Team is withdrawn steadily and slowly, is estimating the number of reimbursable blocks needed, and then exponentially smoothing this value, with an alpha of around 0.25. The hashrate can then be governed by algorithm with no ambiguity or decision-making required.

5. Results and Aftermath

- The Usurpers, even after paying off the Strike Team, mined over 900 extra blocks on the New Chain. Even if these didn’t contain any new transactions, this is still an increase in their total BTC earned, despite using the same hashpower and same total mining expenses. By engaging in the attack and succeeding, the Usurpers in this example are collectively richer to the tune of [12.5*938*5800] = ~60 million USD. (This is a one-time event that affects the overall Bitcoin inflation rate by ~ 0.001%, and much less if the Loyalists surrender quickly [which they probably would].)

- The Strike Team was paid on both chains, and therefore bore no risk of the attack failing. If the Usurpers overpay the Strike Team (using their ~60 Million surplus), the Strikers will be strictly richer by participating.

- In the example above, most Loyalists mined for 3 bi-weekly periods (ie, 6 weeks), at full strength and expense. Yet they earned zero dollars in revenue. They may have lost (at a 20% profit margin), as much as [(200+200+200)*(12.5*5800)*(1/1.20)] = 36.25 million USD.

- Loyalists lose money until they defect, at which point they immediately return to profitability.

- Note that the difficulty on the Old Chain has yet to adjust downward from its full-strength value. Even with about 100 blocks to go, small amounts of hashrate cannot hope to lower the difficulty. Instead the Old Chain must undertake an emergency hard fork to decrease the difficulty.

- Users experience extra-full blocks and extra-slow confirmation times during these six weeks…on the Old Chain only. On the New Chain their experience is normal.

- Users can freely switch from Old to New, at any time. However, the reverse [switching from New to Old] is as cumbersome as trading Altcoins. User’s newly-purchased Old coins will be replayed immediately on the New network (this means that you can freely switch Old-to-New with these coins, as well).

- Users can wait as long as they like before switching (even forever). Their money is waiting for them in the UTXO set of the New chain.

- The Old Chain stops working (in entirety), on Week 7.

6. Achieving Trustlessness

So far, the EF2 requires a slight degree of Inter-MAHF Team Trust: the Usurpers must trust the Strike Team to do their job (ie, to 51% attack the loyalists), and the Strike Team must trust that the Usurpers will pay them.

Can we use our smart-contract cleverness to reduce the need for trust?

One way would be for the New Chain to adopt a new rule (itself enforced by NewChain “soft-fork”, ie orphaning) as follows: every time a Strike-Team block is found on the Old Chain, the very next block1 of the New Chain must contain a coinbase txn that is exactly identical to the coinbase txn that was in the recently found OldChain Strike Team’s block.

This has one problem (which I will fix immediately below), but three additional benefits, which are:

- It maintains total and complete replay-ability among the Old and New Chains (at least, in the Old –> New direction). Even the coinbase txns on Old, are replayed in New.

- Because of that, miners on the Old Chain are allowed to spend their coinbase txn (ie, sell the BTC they earned) during the transition period, as all these spends will be replayed into NewChain. This is helpful because OldChain BTC will eventually be worthless. It is a free consolation prize for the Strike Team. It also allows makes all of the MAHFers indifferent to the length of the transition period. Instead, it is only the anti-MAHFers who suffer during the transition period, and they therefore have extra incentive to surrender ASAP.

- It answers both of these ‘tricky questions’: “How should the strike team be paid?” and “Who should pay them?”. Under this scheme, the payment-mechanism is programmed-in-advance, and the payer is randomly selected by hashrate lottery.

However, as I mentioned, we will need to further refine this payment method, because it has one problematic feature: as soon as a Striker Block is found on the Old Chain, the incentive to mine the very next New-Chain-block becomes zero. As a result, Miners may shirk their responsibilities. For example, miners may temporarily redirect their hardware toward a node for some other SHA256-Altcoin. Such Altcoin-mining would provide the miner with small-but-nonzero reward. Then, as soon as some poor sucker charitably finds the next New Chain block, these freeloaders will switch back! So it is not incentive-compatible.

So, we need a final refinement, one where the NewChain blockward is lowered, but it is not lowered all the way to zero.

The refinement splits the cost over two blocks. First, after the Striker’s reimbursable block, the next NewChain block (Block “A”, see below) must contain an exact copy of the Striker’s coinbase txn, precisely as I just suggested (above). However, now, we do a new thing: the very next NewChain block after that one (“B”, below), must contain a coinbase txn which pays half of its balance to an address that was encoded in the previous NewChain block (ie, an address encoded in Block “A”).

time ------------------------------------------------------>

Old Chain: ----------0------------0----------0----0----------

New Chain: 0-00-0--0---0-0-00----0--0---00-0---0-----000--00-

A B A B A BAB

Zeros ("0") represent blocks. Dashes ("-") represent no block.

B pays half of its coinbase to A.

If two OldChain blocks are found quickly (before two NewChain blocks are found), then the debt is repaid slowly over time in a sequence (see “BAB” in the above figure’s lower-right).

This refinement also provides us with a final strategic efficiency: it forces even the Defectors (not only the Usurpers) to help fund the attack. This is because the attack is funded by softfork-enforced rules that apply to everyone on the MAHF…Usurpers and Defectors alike.

Other Points of Interest

- In theory, the transition period can last an indefinite amount of time; but, in practice, it will likely only last a few weeks at most. Thus, if the MAHFers begin the process right after the OldChain difficulty adjusts, they will always finish the MAHF before a single OldChain difficulty adjustment can take place.

- Miners can loudly claim that they do not support the MAHF, but later say that they “had no choice” but to go along with it. In this way they are immunized from social pressure (for better or for worse).

- It will be easier for the Strikers to 51% attack if they aggressively selfish mine, as they increase their effective-hashpower by a factor of ~1.71 [=.50/.292]. However, to succeed in doing this they must avoid rival spy-mining, which means that a large pool of tightly-controlled hashrate would make for the best Strike Team.

- Normally, users could manually infuse their txns with replay protection, by mixing them with TxIns that are sourced from recent coinbase-TxOuts (these will necessarily be different, on the New and Old chains). However, in this case they can not do this. This is because attacking miners fully control both chains and can force the coinbase txns to be equal (as shown above), or else simply decline to even spend coinbase-inputs until the MAHF is over.

- User cannot hide txns from miners in any way, because they are globally visible on each blockchain. If txns are broadcast only to Loyalist miners, they will eventually be included in blocks; and when those blocks are broadcast, their txns will be read, parsed, and replayed to the Striker’s chain and then replayed again to the Usurper’s chain.

- Because the networks are completely identical and use identical rules, any Lightning Network txns will (as I see it), also necessarily be 100% replayed on both chains. This is because the three major operations of LN (hash-locks, creation of new payment-states, and the invalidation of old payment-states) are completely fungible across both networks.

- The EF2 software is likely pretty easy to develop (in the grand scheme of things). Probably, the best strategy would be to [1] build the concept of “Zone 1” / “always valid” UTXO-updates, and [2] write a third piece of software to track both the Old and New chains. This piece of software would then manually invalidate NewChain blocks if they didn’t meet the criteria I describe above.

- A quirky theoretical point: using my definitions, a ‘spinoff’ is nothing more than an Altcoin that has had a ‘full replay’ up until the point of departure. So the EF2 is conceptually similar to “multiple continuous spinoffs” (something which is already possible today).

Implications

Here I discuss some implications, assuming that the EF2 concept does not contain errors.

1. Miners and Bitcoin Governance

Some people will react to the EF2 with dismay, feeling that it “gives ‘control of Bitcoin’ to the miners”.

What it actually does, however, is give “control over HF-rollouts” to miners. However, to control Hard Forks is not the same as to control Bitcoin. My car turns uses power-steering to turn its wheels, but it is still me who does the driving.

This is because I am about to improve the Evil Fork yet again! I will draw a distinction between a “user-advised MAHF” and a “blind MAHF”. And I will show that the user-advised MAHF will always be economically superior to the blind MAHF. Therefore, the MAHF is not a gift to miners – instead it represents an obligation to seek out (and even pay for!) user-advisement, and then to obey the user.

2. K, The Will of the User

Say that any given hard fork will alter the price of Bitcoin by a factor of K. If K>1, the hard fork will increase the Bitcoin price. If K<1, then the hard fork is bad for the value of Bitcoin.

If K=1, then users are somehow perfectly indifferent between remaining where they are, and going through with the hard fork. If you ask me, this implausible K=1 scenario could only occur if the Hard Fork were just very-slightly better than the original chain, by exactly enough to perfectly-offset the inconvenience of having everyone switch networks.

3. Transparent Justification of Decisions

Obviously, if a hard fork has K<1, it will cost miners money if they succeed in MAHFing. Therefore, if miners know (in advance) that K is <1, then they won’t want to do the MAHF.

However, if everyone knows that K is <1, something interesting happens: then the act of persuading the miners to MAHF is really no different from an attempt to just outright steal some of their mining equipment.

You see? The common knowledge of K makes a big difference.

4. Destructive Entanglement

The EF2 (assuming I have not made errors in formulating it) allows the clean separation of two tasks: ‘deciding on a HF’ and ‘implementing the HF’.

This is wonderful, because the entanglement of these two tasks causes problems for each component sub-task. For example, if Roger Ver goes out of his way to personally pick Jihan Wu up from the airport, is he trying to persuade Jihan (ie, is he corrupting the “decide” process / the “K-measurement” process), or is he just being helpful (making life easier for miners, aka “helping Bitcoin”)? If they aren’t separated, then we don’t know – and, probably, no one knows.

It is hard to understate the significance of this achievement. If miners can “implement” for free, but the act of “deciding” is one which they find confusing and irritating, then this EF2 technique allows them to say “great, come back when you can show us the Proof-of-K” to anyone who asks them to do anything. As I will show later, miners can get all of the benefit of arbitrary hard forks, without doing any work.

5. Simplified Miner-User Interactions

Not only is “deciding” cleanly separated from “implementing”, but both of them are dramatically simplified.

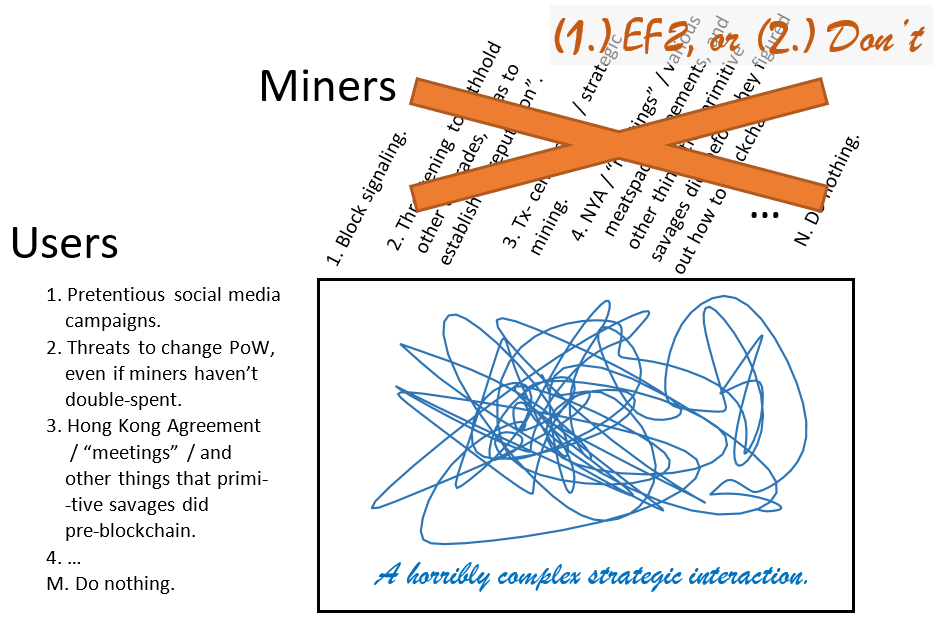

Since the EF2 is the optimal implementation of a hard fork, there is no need for miners to do anything else. No need for “block signaling”, no need for “New York Agreements”, no need for strategic mining or tx-censorship or a giant $100M fund to “kill the minority chain”. All of those strategies are dominated by a plain EF2.

So we get a great simplification:

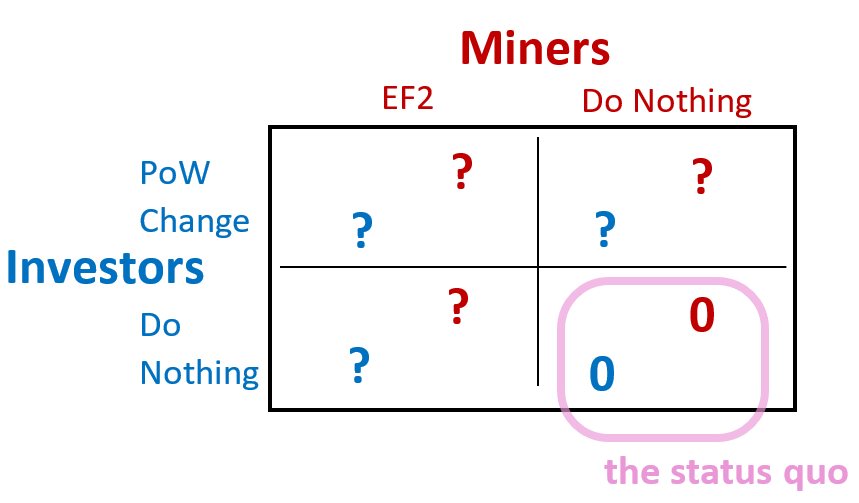

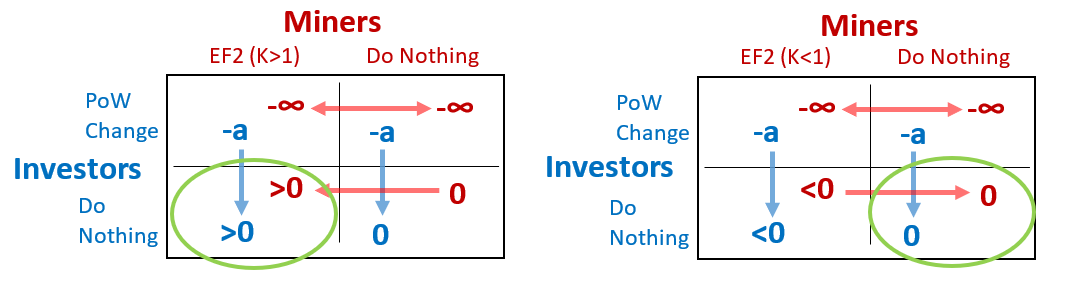

And, since the EF2 is 100% miner-driven, there is only one thing the user can do in response: the PoW-change. So it gets even simpler.

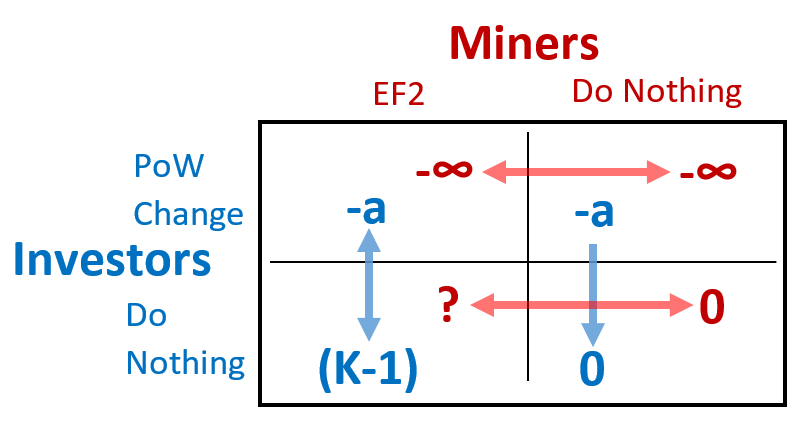

Now, since K=1 implies that users are indifferent to the fork (see above), we can refer to the net effect as “K-1”. Then, we can say that a UAHF to change the PoW will cost the users “a” (but will remove the effect of the MAHF, ie remove the “K-1” effect). Miners lose everything if the PoW is changed, but [for now] we will leave the effect of the fork ambiguous.

Clearly:

- The outcome {“Do Nothing”, “Do Nothing”} is a Nash Equilibrium, if miners don’t want to EF2.

- If a is very large, then it will be too difficult for Users to use the PoW Change. That will describe a situation of no strategic interaction – just some miners making a decision, and helpless users.

- If (a < (K-1)), Users will respond to the EF2 with a PoW Change. Foreseeing this, (and since -INF is lower than everything), miners will never EF2, and the status quo will be the only Nash Equilibrium.

This implies some great advice for anyone who wishes to oppose all EF2s: make a as low as possible. For example, it should be possible to create an infinitely long deterministic list of replacement PoW algorithms (a simple one would be: triple-SHA256, 5x-SHA256, 7x-SHA256, …, but it should be easy to create a list that frequently mixes different hashing algorithms), and then present users with some kind of ‘Emergency Button’ which they could hit. Their nodes would then be open to tracking two blockchain histories at once: the traditional 2x-SHA256 history, as well as a new one where headers are evaluated based on the new PoW (this new blockchain would probably need to start with an ultra-low difficulty, and would need to warn the user to demand 60 confirmations instead of 6).

6. The Meta-Protocol

At this point, I probably sound like crazy person to some readers. I mean, I propose the EF2, in detail (which helps miners)…and now I’m talking about how to stop the EF2. Whose side am I on!?

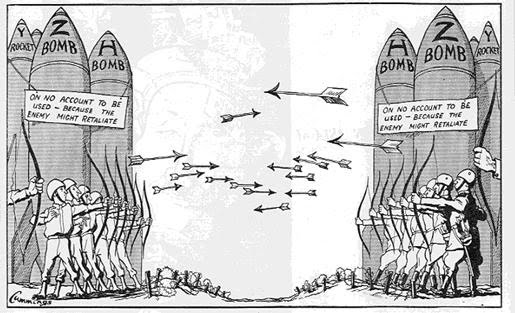

Well, in the game-theory department, things are very complicated and nonlinear. Making your opponent much stronger, can sometimes make your outcomes better. A rival who is strong and tame, can be a valuable ally, but if the ally is too weak to be of any use (and especially if it is using up valuable land), it may panic and try something desperate, resulting in conflict.

Often, “improvements” in strength immediately result in worse outcomes. For a start, they can burden a player with obligations. For example, imagine you are ten years old and you are the only one “able” to fix your family’s computer – you are now stuck doing it, for the foreseeable future! Secondly, being strong can make you stand out – anyone who has ever played Risk knows that it is very dangerous to take an early lead. Soon, everyone will be declare war on you at the same time, knowing that you’re actually the safest player to pick on (as everyone will mask their greed behind a pretext of egalitarianism). Sometimes, making even a hated opponent stronger will result in better outcomes for everybody – imagine that a gunman has taken hostages, and wants to escape via helicopter, but has wounded his leg. If the wound is too serious, he may despair and decide to execute all of the hostages – if one of the hostages is a doctor, it might be best to try to patch him up.

We want very stable equilibria, with lots of weight on both sides, so that nothing is easily disturbed.

An opponent’s strength really isn’t as relevant as his ability to surprise you, or do something ambiguous. Especially in this case – the user’s weapon against the miners is a PoW change, but it is both too slow and too imprecise to be an effective micromanagement tool. So miners are dangerous when they are fast, or marginal.

So, what we don’t want is, crazy experiments like these coming out of nowhere, and possibly leading to conflict. Instead, we want a publicly known process, that works very slowly and precisely.

And the process has to be valid. If a given hard fork actually is best for users, then the process has to ultimately result in the hard fork happening. The validity of the process, is the ‘secret sauce’ – that is what allows all of us (miners, investors, users – whatever our BlockSize views) to rely on this process, and safely ignore everything else.

In other words, the process has to “solve” the problem of Bitcoin governance – or, at least, of Hashrate Governance2. If K is high, the fork should always go through, if K is low, the fork should never go through. No need for talking, or dominance games. Fortunately, Hashrate Governance is very simple: hashers should mine whoever pays them the most – ie, whichever blockchain gives them the most profitable coinbase txn.

This happens to overlap with the investor’s goal, which is to increase his ROI as much as possible. In fact, miner’s profitability is maximized by servicing investors and users as well as possible.

Since the miner’s and investor’s incentives are the same, then any miner-errors can only be earnest mistakes.

What can miner’s do, in order to minimize their mistakes?

One thing would be to emphasize “a process that corrects errors over time”. Any error contained within the K-measurement process should be removed as quickly and efficiently as possible. Bad agents should find that the process is working toward kicking them out as quickly as possible3. The process should ultimately broadcast a (“fork”, “don’t fork”) signal, and one that is simple, cheap, and easy for all users (even ones that aren’t technical, or don’t speak English) to monitor, understand, and criticize. That’s the heart and soul of science: openness to criticism.

Fortunately, we have such a process!

7. Publicly Measuring K

K can be measured publicly, and accurately, using “fork futures”, either using existing exchanges, or, if exchange-counterparty risk is a concern, a multisig smart contract.

Fork futures also achieve a separation of the “decide” and “implementation” processes (see “Destructive Entanglement”, above). While the EF2 focuses entirely on “implementation”, Fork Futures focus entirely on the “decide” process. They allow us to examine the effect of the fork on the BTC/USD price.

Today, some miners feel that they’ve seen enough evidence to support SegWit2x. They think SegWit2x maximizes the value of their coins.

Well, maybe that’s what they think. Who knows what miners have decided, or why. Maybe they haven’t actually based their decision on anything at all, and it is all just a ploy to make more money day trading. Or maybe they are being coerced, or perhaps it was the Chinese government that was really blocking SegWit (and miners were secretly grateful for the UASF pretext). Or perhaps the miners are just too busy/frustrated to care about any of this. Who knows what they’re really thinking?

Wouldn’t transparency be better? Shouldn’t Bitcoin not rely on their opinion?

I think that these three skills [1] 2x-SHA256 mining, [2] developing software, and [3] forecasting a technology’s future usefulness, are almost completely unrelated. Someone who is exceptional at one, is likely to be mediocre at the others. Shouldn’t we try to find the forecasting specialists?

And especially when the stakes are so high! At (12.5+1) BTC per block, about 710,000 blocks are mined per year; at $5800/coin this is 4.1 billion dollars in revenue. A mis-measurement of K, by 1/10th of one percent, is worth over four million USD. Who, or what, is giving us our best K-measurement? How can we be sure? Over time, will our K-measuring process become more or less accurate?

With these amounts on the line, miners owe it to themselves (and their shareholders) to get the best measurement of K they can find.

Especially because…

8. Betting Blind

If I had to bet blind, I would go with Bitcoin Core/1x, and not 2x. But, why on Earth would anyone bet blind, ever? I don’t drive my car blind. And if I lost my eyesight, I would stop driving…I’d just Uber/taxi everywhere. And if there were no Uber I’d walk. And if I couldn’t walk I’d stay in my house. I mean what kind of idiot drives a car blindfolded?4

Miners certainty shouldn’t bet blind. And they shouldn’t listen to anyone who tells them to bet blind, either. Anyone can create decent futures markets with $10,000 and a weekend.

With these markets, miners can turn a gamble into a sure thing. Let me explain.

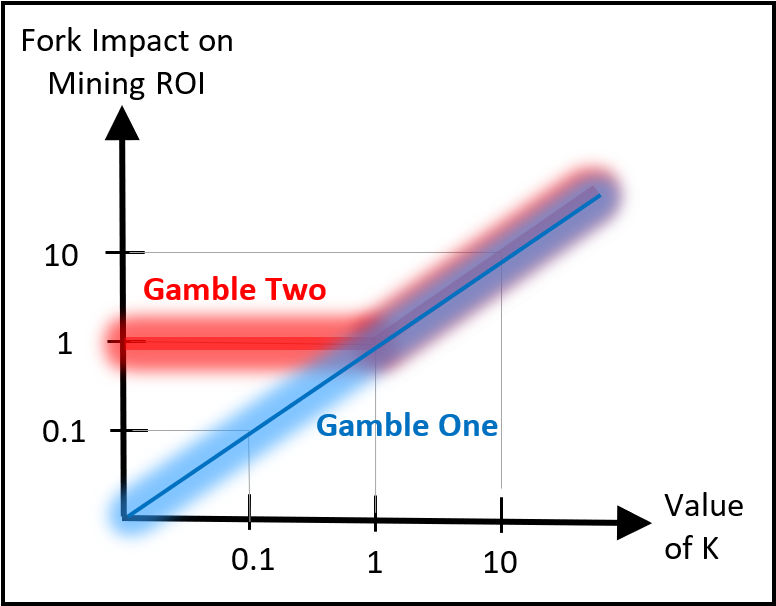

Consider this scenario: first, the MAHF in question is a contentious one – we can expect some users to reject the New Chain, by making a new-PoW spinoff of the Old Chain. Second, imagine that miners do the MAHF “blind” – in other words, they do it without first measuring investor sentiment with “healthy” futures markets.

( I define a “healthy” futures market as one where: [1] it exists, [2] people are aware that it exists, [3] transaction frictions are low (ie, fees, counterparty risk, basis risk, etc), and [4] liquidity is non-negligible. This definition is part of a forthcoming blog post. Miners have good incentives to ignore PMs which are badly-designed or unhealthy. )

In this scenario, miners have made a rather peculiar gamble. I will call it “Gamble One”. It is as follows: they have wagered their entire stock of equipment (and all of their in-pipeline equipment, including design expertise), that the New Chain will be worth at least as much as the Old Chain. If they are right [about New > Old], then they make some money. But if they are wrong, they lose some money.

This gamble, “Gamble One”, is made in real life with real stuff. But, curiously, it is almost identical to a trade that they could make in a futures market, if one existed. Specifically, if ‘Fork Futures’ existed, the MAHFer’s actions would be akin to a huge bet, ‘going long’ on the 2x futures with the entire total value of all their stuff.

But, the cool thing is: miners have an alternative to Gamble One, and it is better for them and better for the ecosystem as a whole. I will call it “Gamble Two”, and it is for miners to wait for the future’s market’s report, and then only actually go through with the MAHF if K is >1.

Gamble Two is undeniably better. It has all the upside of Gamble One, but none of the downside. For any given kind of Hard Fork, its “Gamble One” will be worse: it will have a lower return, and a more volatile return, than its “Gamble Two”. Seeking a measurement of K is a no-brainer.

And once K is known, the Nash Equilibria are obvious:

As icing on the cake, the investor never has to do anything. How perfect!

9. Interaction vs Optimization

A Land Metaphor

When people own land, then they have an incentive to build improvements on the land. And since these improvements are so vital to human life, it shouldn’t be surprising that civilizations with clear land ownership policies tended to thrive, relative to civilizations that lacked such policies.

Probably, in the grand scheme of things, the question of “Who owns this land?” is less relevant than the question “In this civilization, can land be owned?”. Once someone owns the land, there will be more and more improvements which, through capital accumulation, will eventually benefit everyone. Better to rent, in a world with electricity, than be free to wander around across a bunch of worthless mud.

Mysteries of the Blocksize Conflict

Currently in Bitcoin, the miners are having some negative interactions with certain other members of the community. This led to SegWit being held hostage, in return for a blocksize increase…despite the fact that it was a blocksize increase.

Moreover, miners can already make the blocksize whatever they like, using extension blocks (which are far easier than the EF2). And, if devs cared about keeping blocks small, they would put all of their weight behind sidechains, so as to safely redirect unsatisfied customers onto a different computer network5. And if “blocksize” was such an important variable, both groups would want to objectively measure the optimal blocksize, not only to learn the truth, but also for the selfish purpose of making their own case most persuasively. But instead no one is interested in doing this.

Therefore, the dispute really can’t be about the blocksize. Instead, it is about status (ie, “respect” and “influence”). Believe it or not, there are LargeBlockers out there, who want 2x succeed only (or mostly) because they take offense to the statements of a few devs. They want to “fire the devs”. And, not to be outdone, most SmallBlocker anti-2xers object primarily to “the process” by which 2x was created. That is a good reason to oppose the process, but a bad reason to oppose the 2x idea itself (in fact it is an ad hominem fallacy6, full stop). Both groups want to be important, or to have their leaders and associates be treated with respect.

Dominance Contests

Since status is the goal, we shouldn’t be surprised that people engage in behaviors that have a social focus (instead of an engineering focus). It is rational for an insecure leader [especially of an up-and-coming group] to try to do something crazy to assert his dominance. The crazier, the better.

But this conflict is pointlessly destructive. It is far better, if the dominance contest ends as soon as possible; so that whoever “owns the land” can turn their full attention to using it most productively.

Which I believe the miner’s will. Miners are the only group who do not freely inherit both descendant-coins, in the case of a spinoff. So, they should hate spinoffs more than anyone. They’re stuck on just one chain – the only thing they can do is make the most of it.

10. “Of Course You Would Say That”

Since “miners can use the EF2 to unilaterally MAHF” is TRUE, it follows trivially that “miners can MAHF without community support” is also TRUE.

This simple fact has some surprising implications. For starters, anything miners say in support of a given MAHF is immediately suspicious. Anything that they say they believe, in support of a MAHF which actually does have community support, would sound exactly like a pretext they’d pretend to believe if they were instead advancing a miner-selfish, not-community-supported MAHF. Miners experience the problem of The Market for Lemons – miners are trying to sell a great car, but no one will believe them.

So, ironically, the existence of the EF2 [a unilateral MAHF option] actually neutralizes the miner’s “vote”. Any input, opinions, and comments coming from the mouth of the miners is far less relevant – either they are going to move the chain or they aren’t.

Hence, miners will probably need to turn to Fork Futures – not only as a source of information [about which fork is best], but also as a way of justifying their decisions.

Conclusion

This post, while at first about replay protection and evil forks, ended up tackling large questions of Bitcoin governance. Using the EF2, miners can transition the network to any chain they like. Perhaps they will transition the network to a better chain. Or maybe they will carelessly screw it up, destroying themselves in the process. Smart miners will use evaluate different chains in a variety of ways, especially futures markets.

The existence of EF2 might grant miners absolute ‘control’ over a hard fork process, but that certainly does not grant absolute governing-power. If that were the case, then bailiffs would be more powerful than judges, office security guards would be more powerful than CEOs, and demolition/construction-laborers would be more powerful than landowners.

You see, what this post really does is take control away from both devs and miners, and give it to investors. It grants the miners an option to unilaterally hardfork, but in a way this just calls the hardforker’s bluff. They say they want to do a hard fork and now I’ve given it to them. But with the good comes the bad, with the bitter comes the sweet. For it is now the case, that any large screwups will be attributed to them alone. Imagine if I irrevocably gave you sole and complete control over the USA’s nuclear ICBM arsenal – it’s really more of a burden than a gift. I’ll just be chillaxing over here on the beach, while you handle all that the geopolitical stuff…good luck!

Perhaps this will turn out to be a horrible mistake, one that results in needless network turbulence. But I almost think it must be worth it, just to have some peace and quiet around here. Finally, there is no need for anyone to say anything about the blocksize any longer!7 And even less of a reason for anyone to listen! The civil war is over.

Footnotes

-

Or instead, for network synchronization reasons, the “next block that is at least X minutes after the network time of the Strike-Team block’s network time”, or “with a lag time of two blocks”, or some other variant. ↩

-

Of course, “Bitcoin” is a digital commodity, and it does not have “governance” (just as Wheat, Gold, and Hydrogen do not have “governance”). Each individual Bitcoin protocol (for example, the protocol corresponding to Core 0.14.2), is governed by “consensus”, which is to say, mandatory 100% agreement. The Github project that we know as “Bitcoin Core” is a Wladimir dictatorship. A soft fork will guarantee that all software projects are tracking the same commodity – ie, that the “Bitcoin” of Bitcoin Core 0.14.2 is the same digital commodity as the “Bitcoin” of 0.8.1. ↩

-

Note that the current process of “trusting the experts” is not a good one, because if anyone starts trusting a bad expert, the system’s efficiency plummets. And how do you tell the good experts from the bad, unless you are an expert yourself? Thus it becomes circular logic; useless. ↩

-

In other words, while I lean towards 1x/Core, I have an open mind. The 1x/Core philosophy is mostly dev-worship, but the devs make a lot of Type-I errors (violently rejecting some good ideas, and then quietly later adding them); we really don’t know, by definition, what would happen if a more welcoming door were opened to more devs. The 2x philosophy seems mostly uninformed and hapless, but I am totally protected from their mistakes, first by my node and second by the market. So, its possible that there would be faster progress if we cranked the volatility to sky, and just tried more stuff. So while I side with Core/1x, I don’t pretend to know everything. ↩

-

I find it interesting that drivechain sidechains are very similar to extension blocks, yet [1] all transfers from ext-block to main-block are always valid, and [2] these xfers are constrained so as to minimize the liklihood of fradulent xfers. An extension block is very much like a mandatory sidechain (which largely defeats the point of being a soft fork). ↩

-

It doesn’t matter if a good idea was created by Greg Maxwell, Roger Ver, Jamie Dimon or a computer that periodically generates ideas of random quality. A good idea is just a good idea. (Same for a bad idea.) ↩

-

Bitcoin shouldn’t care what anyone says on social media, nor should it care about who was around to hear, or who agrees. All of these “meetings” and “agreements” and “conferences” and “tweets” are nonsense at best, and an attack-vector at worst. Decentralists should work toward their irrelevance. The transparent, scientific (criticism-friendly) measurement of K is the only important thing. ↩