Part 3: Why Two is the Optimal Number of Parties

Our two-party system often fails us – its gives us two bad options.

A common reaction to this, is: let’s add more options!

A. Intro / Summary

After all, they can’t all be bad. Eventually, just one good candidate will sneak past the first filter, onto the ballot! Then – we’re all saved! We can all just vote for that good one.

This well-meaning idea, is false.

Which is pretty strange! Because, usually, it would be true. In CVS, more choice always benefits consumers. (And it always harms producers.) If you are Crest, then your rival [Colgate] is a thorn in your side. His success is your misery. And, if even more toothpaste entrepreneurs enter the market, with yet more options (Aquafresh, etc) – then your misery increases. It is like a tabletop game of Risk, where you are attacked on multiple fronts. More choice always means stronger competition – more choice always benefits consumers. (Since, at worst, they can ignore any new options, and stick with the status quo). More choice, always means more stress on producers.

With voting it is the exact opposite. If you are the Ruling Party, then the Opposition Party is a thorn in your side. They are your biggest critic – they are the source of your accountability. They are your biggest threat. But, as I will explain, more new choices always means weaker competition – the more parties there are, the more divided the opposition is – amongst itself. It is like a game of risk where your opponents fight each other exclusively – while you relax. Picking them off one at a time.

“More parties” does not solve our Pre-Campaign problem. And – it creates new, horrible problems that are even worse. It is the wrong “solution”, to a “problem” (representation) that should not be solved in the first place.

And I will now explain why.

B. The Infinite Regress

No matter how many parties there are – 2 or 20 – there will always be just 1 government.

That govt, will either declare war on Afghanistan, or it won’t. It will either allow gay marriage, or it won’t. The interstate highway system, will be built to a certain length and width, or it won’t. The tax rate on a certain activity, will either be 15%, or 18%, or 0% – but it can’t be all of them at once. It can only be one. The government can only be one thing, at a time.

Therefore, the “problem of government” is not “how to represent 350 million Americans equally” – instead, it is “how to cross off ideas until we narrow it just one”. We must shorten the list of ideas – [of all the ideas in everyone’s head] – until only 1 single idea remains. (This is the idea that the government will actually do.) Adding more political parties is going the wrong way.

With 350 million unique political parties (for example), everyone would be equally “represented”, but the “parties” would be useless. We would have the original problem all over again: which parties to disqualify.

So we have our first clue. 350 million unique parties, would not give us any more choice.

But perhaps there is an optimal trade-off? Maybe 5-10 parties would strike the right balance?

C. Strategic Voting and Spoiler Candidates

“Majority Rule” voting says: if you get the most votes, you win.

In this type of voting, any third option will split the vote among the two most-similar choices, such that neither can possibly win. For example, imagine a country is initially split “40-60”, between two parties, “left” and “right”. Then imagine a new party appears that is Ultra-Right. This 3rd party is better – it attracts a few left voters and a few right voters, leading to a 38-37-25 split. Even though more people have moved rightward, the outcome (under majority rule) is that the left party wins, with 38%. We’ve split the vote.

So, with simple majority rule voting, 3rd-parties screw everything up. We have gone from bad to worse – out of the frying pan, and into the fire.

But, if we desire to have more parties, then why not change the rules? We can used ranked-choice voting, or multiple-rounds, or something else. Why not?

Well – as we will see, those ideas all move us even further in the wrong direction. Having jumped from the frying pan into the fire; we are now asked to jump again – from the fire, into a blast furnace.

D. Proportional Representation

To increase the number of parties (from 2 to 5, for example) you may use proportional representation or “PR”.

This terrible idea, is very popular around the world. Continental Europe, mostly uses “closed list” PR. Central America mostly uses “open list PR” (which takes a terrible idea, and makes it even worse).

(I will propose my ideal democracy, in Part 7.)

The European version, at least has “brands” (a la Crest vs Colgate), where you vote for a party. That’s the good news. The bad news is that it is not winner-take-all. If your party gets 10% of the vote, you get 10% of the Congressional seats.

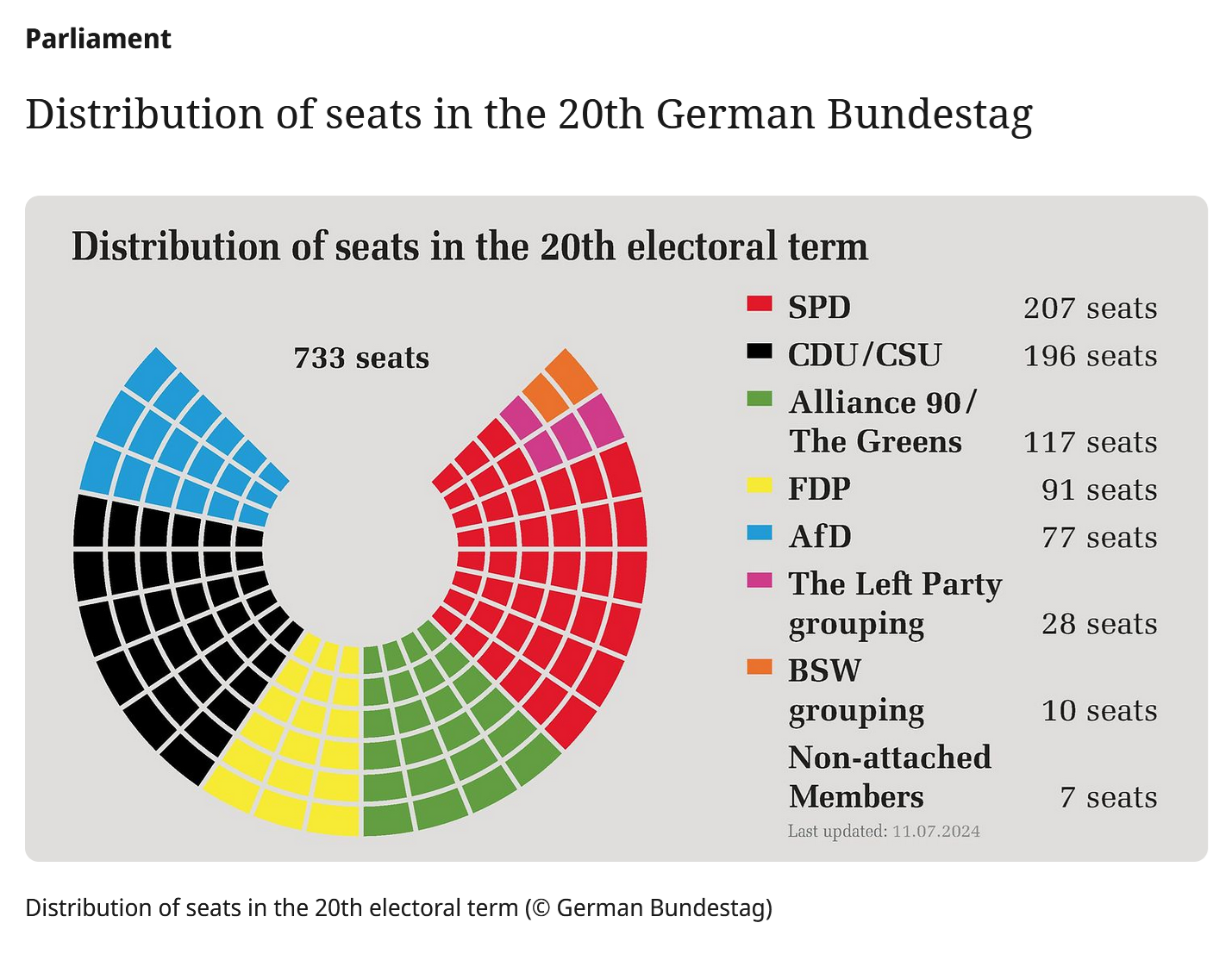

Germany (a PR country) is ruled by 5 major parties, instead of 2:

Such countries are ultimately ruled by “coalition governments” – where the smaller parties must negotiate and merge, until one coalition comprises >51% of the seats.

E. Welcome to Hell (Coalition Governments)

At first glance, this might not sound so bad.

But it is.

It’s so, so bad.

First, notice that the coalition phase is the real election – the coalition ultimately determines what the One Government will do. The “fake election”, in contrast, was what millions of German citizens did on “election day”. Election Day in Germany is meaningless, for the following reason: unless 51% of the Germans vote for one party (which [1] defeats the whole point of their multi-party system, and also which [2] –more importantly– has never happened [and probably never will]), their vote has no effect on what the government ends up doing. It is effectively just a straw poll.

I am exaggerating – but only very slightly.

Let me give you a numeric example. Imagine there are 4 parties, and the vote count (on Election Day) is: 42% 33% 18% 7%. Thus, in a German Congress of 100 senators (or whatever), the number of senators in each party would be [42,33,18,7] – same as the percentages. Now, they must form a coalition. Perhaps the Top Two will merge? That would give them 42+33 = 75%.

But – you can see that the 3rd-largest party (18%), could itself reach 51%, by coalition-ing with either #1 or #2. It can freely choose one or the other, paying no price for choosing party #2 (even though #2 got much fewer votes). Party #1 got the most votes, but it gets no reward for this achievement. Party #4 is now “represented” in Congress… if by “represented” you mean “they are allowed to sit in the same room” as the 3 relevant parties. The vote total, on election day, might as well have been: [1,1,1,0], instead of [42%,33%,18%,%7]. PR just “gerrymanders” all the voters of one party into a single district (see Part 5) – it is a kind of “Electoral College” on steroids.

Sometimes the two largest parties manage to [form a

coalition], but the most common outcome is that the

leader of the third-largest party holds the 'balance

of power' and decides which of the two largest

parties shall join it in government, and which shall

be sidelined, and for how long.

-David Deutsch, Beginning of Infinity, Chapter 13

The 3rd-largest party is, by definition, one that most voters did not vote for (mathematically, it can never have more than 1/3 of the votes – meaning that more than twice as many votes were cast away from this party, than for it). And yet here, it has been elevated to king-maker. On a whim, it can select either party #1 or party #2. This is no democracy at all: it is a dictatorship. Whoever is running the 3rd largest party, has the only vote that matters.

The Party Boss, of party #3 may not even be a politician. He may never have been elected. He may never have campaigned. Yet, in a PR “democracy”, he has become the #1 most powerful person in the government (and in the country).

As Deutsch continues:

In Germany (former West Germany) between 1949 and 1998,

the Free Democratic Party (FDP) was the third largest.

Though it never received more than 12.8 per cent of the

vote, and usually much less, the country's proportional

representation system gave it power that was insensitive

to changes in the voter's opinions. On several occasions

it chose which of the two largest parties would govern,

twice changing sides and three times choosing to put the

less popular of the two (as measured by votes) into

power. The FDP's leader was usually made a cabinet minis-

ter as part of the coalition deal, with the result that

for the last twenty-nine years of that period Germany

had only two weeks without an FDP foreign minister. In

1998, when the FDP was pushed into fourth place by the

Green Party, it was immediately ousted from government,

and the Greens assumed the mantle of kingmakers. And

they took charge of the Foreign Ministry as well. This

disproportionate power that proportional representation

gives the third-largest party is an embarrassing

feature of a system whose whole raison d'etre, and sup-

posed moral justification, is to allocate political

influence proportionally.

This is only the tip of the iceberg.

In PR, the coalition can sometimes dissolve, or reform, even if the voters were happy with the status quo. After all: the Party Boss #3 can change his mind.

Worse, when voters cast their ballot on election day, they do so, without knowing which coalition(s) will form. That’s right: they don’t know what government they are voting for!

But this means there is no connection between “the will of the people” and the government’s behavior. The government’s future behavior is known to be unrelated to the way that people just voted. No politician has any particular reason to care about obtaining more votes (they work for the party, not the voter). Thus, the whole thing is a sham. The voter has no particular reason to care how he himself votes. He (or she) has no reason to research the issues (and modify his vote based on new information). In turn, the local newspapers have no reason to bring truthful, relevant information to citizens. Nothing matters, nothing can be fixed, nothing is ever learned, and no one knows how to change anything.

So – if this system is so bad, then why is it so widely used?

F. Representation vs Accountability

PR systems are supposedly better, because they “represent” more groups.

But – this whole “representation” business is way overrated.

First of all, it is fundamentally incoherent, since (as I’ve explained) the government will ultimately only do 1 thing. Only one government action is “represented” in our physical reality. What difference does it make, if there are XYZ number of black people, or QRS number of women, ZYX number of gays, standing in the Congress building when it happens? They might as well be standing in their homes.

Second, it is a complete ad hominem fallacy. No one cares how we got to our result; what matters is the result. We want good results. Imagine that Policy Q is what is best for black people. Then, does it matter who came up with Policy Q, or if a black president is the one who signed it into law? No – it does not. A doctor does not need to himself have cancer, in order to treat a patient’s cancer. An electrician does not need to be a woman, in order to fix a woman’s power lines. The politician’s job –to rightly govern the people– is a job like any other. It has its own objective rules, that anyone can master. To insist that the Congress “resemble” the electorate, is superficial at best, and insulting at worst.

Third, “representation” inherently targets mediocrity – and it rejects greatness. The average citizen has average intelligence – not high intelligence. They have average knowledge of geopolitics, average knowledge of economics, law, culture, diplomacy, conflict-resolution, compromise. What if your plumber only had average knowledge of plumbing (ie, almost none)? What if your heart surgeon had only average knowledge of anatomy, or of medicine? The “resemblance” concept is a lost cause, anyway – a politician will differentiate automatically. Merely by winning the election, and becoming an elected politician, they will become different – they will get security clearance, they will be briefed on important matters of national security, they will have their own bodyguards and staff. To become an elected politician, is to become different than the citizen. Everyone is a specialist at something.

What people hate, about politicians, is [1] when they give us bad results, and [2] we are powerless to change the situation. This is how representation takes hold, in people’s minds. A politician lets us down – the job doesn’t get done. People get annoyed. They poke their head in. They think: “I need to look into this, because these idiots are screwing it up”. That is when temptation strikes: “We need more people like me, to fix this organization.” Or – (if this organization is going to be corrupt anyway), then I at least want my people to grab some corruption, for me.

Thus, “accountability” is more important than representation. Politicians are skilled at evading blame, and so our institutions must be correspondingly skilled – at nailing the blame back to them. Blame must “stick”.

G. You’re Fired

In PR, elections don’t really matter.

Admittedly, a few seats might change in Congress – but no one actually suffers. (Some politicians lose their seat, but their party can find them a job elsewhere.) The Boss of the 3rd-largest party, is unaffected – even if most voters hate him. His coalition can continue as before.

Contrast that, with our two-party system. In a two-party system, the Ruling Party is truly fired. They go from total control of Congress, to zero control. They go from total control over the military, to zero control. The $7 trillion budget (some of which they [assuredly] funnel to their friends)? It goes from 100% control to 0% control. Their influence goes from everything… to nothing.

It is misleading to call “majority rule” a “winner take all” system. Instead, it should be called a “loser-lose-all” system. The Ruling Party will lose everything – unless they can outscore the Opposition Party (in votes), time and time again, forever.

The more they have to lose, the more motivated they will be, to win over our vote. This is true accountability, because it connects failure with suffering. If the Ruling Party makes us suffer, then we reflect this misery back at them. It’s forced empathy. Our problems become their problem.

H. The Anti-Vote

It may be easier to appreciate the two-party system, if we consider the “anti-vote”.

By “anti-vote”, I mean: how many people voted against you. How many people blame you, for your bad ideas. And want to fire you.

In a two-party system, this distinction does not matter. Votes and anti-votes are redundant – mirror images of each other. If there are 100 voters, and you get 60 votes, then both of these sentences are true: [1] you are winning the vote 60-40; and [2] you are losing the anti-vote 40-60.

Furthermore, in a two-party system, these sentences have the same meaning: [1] “if the Opposition Party gets more votes, then they win, and are put into power”; [2] “if most of the votes are cast against the Ruling party, then they are fired, and removed from power”. In a two-party system, every anti-vote a Party receives, the more likely they are to be fired – and the more nervous, and frantic they will become.

Multi-party systems lack this feature. If we have 5 parties total, and party #3 loses votes to party #4, then who is punished? Without knowing its effect on the coalition, we have no idea. There may be no effect.

Or there may be a reverse effect. Voters could move to the far-right, forming a completely new far-right party. Are left-party Boss(es) punished for this? Not at all. Their vote total (and anti-vote total) remains the same. In fact – they now have more right-party Boss(es) to potentially form a coalition with. These right-party Bosses must now compete with each other – decimating their individual negotiating leverage. Although we did not “split the vote”, literally (as would have happened under Majority Rule), the result is the same: it is the strategic voting / split-the-vote problem all over again. This is the very problem that PR was created to solve - but when viewed through the lens of anti-votes, we see that it does not solve this problem at all.

I. Comparisons, Elections, and Legitimacy

The ideal quantity of parties is two, (in part) because the ideal quantity of comparisons is one.

With just two parties, (A,B), only one comparison (A>B) is needed. In contrast, four parties (A,B,C,D), would require six comparisons (A>B,A>C,A>D,B>C,B>D,C>D); and five parties would require ten comparisons. (By the formula n*(n-1)/2 .)

But we can only afford one comparison. Each comparison is essentially its own election. With one election, we have finality and closure – we all know what happened, and why. We knew to put 100% of our effort, into this single event – that we all pre-agreed was the legitimate one (and which has no rival). In contrast, two elections (or more), means that each de-legitimizes the other(s). Which election should we pay attention to, and why? Which comparison was the real one (and which one was rigged, or had irregularities).

Multiple elections is like wearing multiple eyeglasses – not helping; and instead all interfering with each other. Our core task (Section B, above) to eliminate options, (and disqualify policies), narrowing it down to just one policy (which the government then implements).

J. One-Party “Democracies”

( By the way, I hope it is now clear, why the “one-party” democracies [Russia, China, North Korea, etc] are all total shams. If it isn’t clear by now, I daresay that it will be, by the time the essay is over. “One-party” means: no competition, no anti-vote, no threat to the Ruling Party, no recovering from mistakes. )

K. Conclusion of Part 3

In economics, the phrase barriers to entry refers to how easy it is to start a new competitor. When barriers are low, businesses treat their customers (and employees) well – they have no choice. Even in a superficial monopoly (when one firm is the only game in town), rivals are champing at the bit, waiting in the wings, ready to move in and quickly take marketshare, at the first opportunity.

With voting, the barriers to entry (for the 3rd-party and beyond) are, regrettably: infinite. We are stuck with just two options.

Political competition cannot be improved via adding a 3rd option. (We will have to improve it a different way – and we shall.) It is impossible to start a new party – in the sense that nothing politically useful can be achieved that way. The UK/US-style voting (aka “majority rule”, aka first-past-the-post), explicitly discourages 3rd parties (and rightly so). European-style “proportional representation” attempts to encourage multiple parties, but in practice achieves only [1] the disenfranchisement of all citizens, and [2] titanic-scale jerrymandering – aka a disaster. (Adding insult to injury, it also fails to achieve anything remotely close to “proportional representation”.)

Multi-party systems reduce the government’s motivation to obtain/keep our vote, making a mockery of democracy and turning Election Day into a straw poll (ie, a pointless event with no consequences).

For these reasons, multi-party systems are inferior to two-party systems (see Part 10 for more).

It takes a thief,

to catch a thief.

-Idiom

A political party is a frightening thing, and it can only be kept in line by a second political party. Let us not weaken our lone defender.

Part 4: Bad Nominees

We now return to our key question: on Election Day, why are the two choices so bad?

A. Recap

We have two clues, so far:

- [Part 2] No one “takes responsibility” for the Pre-Campaign. When the Pre-Campaign sucks, no one is blamed. The job –of “baseball scout”– is not being done. And we don’t know who is screwing it up, or how to fire them.

- [Part 3] A two-party system is optimal – so we are always stuck with two options. A new high-quality candidate, cannot start his own party. He must rise through one of the two existing parties.

We will now discuss the process by which a candidate “rises” in a party.

B. Two Types of Motive

In Goldeneye (1995), James Bond selflessly puts himself in harm’s way, for the good of his country [England]:

Alec: James, for England.

Bond: For England, Alec.

Imagine two types of party-member:

- Selfless – Dedicated completely to what is best for the party. They will make any sacrifice needed, to increase the Party’s odds of winning on Election Day.

- Selfish – Dedicated completely to what is best for themselves. Will only help the Party, if the party reciprocates by advancing their political career.

In practice, each politician is (probably) some mixture of the two.

Also – keep in mind: after you are chosen, as Presidential Candidate – then there is near-perfect overlap. From the nominee’s point of view, “winning the general election” is what’s best for them, and their party.

But – what about before? What about during the Pre-Campaign?

C. Two Types of Competitive Venue

Of the two types (selfless and selfish), who is more likely to rise to the top of the party?

(By “rise”, I mean: [1] more likely to be chosen as Candidate themselves, or: [2] more able to influence the Candidate-selection process – for example, by helping to “narrow” the shortlist down to just 16 primary candidates.)

Well, the Selfish people have a clear edge – they are constantly moving up. They use every ounce of cunning they posses, to advance themselves within the party. In contrast, the Selfless people have a standing disadvantage – they are constantly sliding down the ladder, in order to help The Party defeat its rival.

Thus, each party has two competitive venues. On one hand, is the external venue: the epic battle on Election Day, between Ruling and Opposition parties. On the other hand, each party has its own internal venue: the current party leaders, vs the aspiring leaders who rise up to challenge and replace them.

[Nancy Pelosi] won an eighth term as leader in November 2016 at

the age of seventy-six, despite having led House Democrats to

four successive electoral defeats. That would be unimaginable

in a parliamentary system, where backbenchers do not long tol-

erate leaders who cannot deliver victories.

-Responsible Parties, p114

It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way

of making decisions than by putting those decisions in

the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.

-Thomas Sowell

D. The Corrupting Incentive

Ideally, the most qualified person would get the job.

At the tip-top of each party –ie, the Douche and Turd that end up on the ballot– are the two best at climbing the internal venue. At internal-climbing, they are the best of the best.

But are they the most qualified to win the election – (let alone run the country)?

On one hand, “you can only serve one God” – so there is an inherent tension between the two. On the other hand, presumably if you are highly “electable”, then this will help you rise in the party (since parties do want winners). So, it must be a mix. The top of the party will be A+ internal-climbers, but perhaps only B- general-election-winners. (Of course, they might be F-grade general-election-winners, for all we know.)

Unfortunately, “electability” is hard to measure, before an election. (And, after the election, it is obviously too late to go back and pick someone else – ie, someone more electable [who would have won].)

Furthermore, the low-electability candidates would want to cover up that information. By concealing their un-elect-ability, they increase their odds of being named candidate. This harms the party, but helps them. (Notably, prediction markets [on candidate electability], have faced an uphill legal battle for decades.)

This temptation to conceal known flaws, is what I call the corrupting incentive. At the end of the day, I bet Hillary Clinton would admit to herself (secretly): “Out of everyone the party could possibly run, I am probably not the best candidate. In other words, I am not the single candidate with the highest likelihood of delivering a victory for this party”. (I think even Trump would admit that.) Of course, Hillary and Trump are the best [the best in the world] at something else: climbing the internal venue. They are the best, at fighting to the top of their party – and boxing out their rivals. We all admit that – even the two optimal Candidates (wherever they are – ie, the Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister, who are never nominated), would admit that.

Thus, the paradox: Clinton-2016 (and Biden-2024) intentionally make a mistake. They choose themselves, as Candidate, even though they know that they are not A+ players (in the external venue). Their choice harms their party – and they know it will harm their own party – but they do it anyway. Out of selfishness.

E. The Long Leash

In a two-party system, there are only two choices. So, the only source of competitive pressure, is the other party.

If one party starts making mistakes – (ie, acting corrupt, nominating bad candidates, etc) – then this unilaterally puts the other party on a longer leash.

It is akin to a love triangle – between two men and one woman. (We the voters, are the woman – the candidates, are the two men, vying for our affection.) We are required to pick one of these two [as our romantic partner] for 4 years.

Imagine we choose the Democrat. How much leverage do we have, over this person? Can we get them to clean up around the house? Can we get them to hit the gym? Or put in more hours at work? The answer is… it depends.

It depends on how awful the Republican alternative is. If the Republican is a boorish slob imbecile who is constantly drinking and getting himself arrested, then our Democrat-boyfriend will feel very smug, and very comfortable. He will say: “Hey – I’m not so bad, am I?”, with a grin, as he leans in for a kiss (etc etc). In contrast, it will be quite a different story, if the Republican is a jacked, wealthy, church-attending courteous family-man who buys flowers every Valentine’s Day. Then, our Democrat-boyfriend is on a much shorter leash. Suddenly he feels a lot less entitled – and will tend to be on his best behavior.

In other words, it is precisely because Colgate is so good, that Crest has no choice but to step-up its game. And it is precisely because the Douche is so flawed, that the Turd-party does not mutiny when the Turd (also flawed) is chosen.

F. Mutiny

By “mutiny”, I mean: “upgrade the candidate to a better one”.

(Ie, a “mutiny” is when a party takes responsibility for its defective internal venue, and performs error-correction on it.)

Biden suffered a mutiny, after his 1st debate – Democratic leadership knew that Biden would lose the general election. They had no choice but to “fire” Biden. Their current effort-level was too low – so they stepped it up.

But… why wait?? Didn’t they foresee that Biden would lose the debate? Why not step up their game earlier?

In fact – why not step it up… all the way? Ie, enough to win. Just keep mutinying, [over and over] until the Perfect Candidate is chosen. Refuse to accept any candidate, except a near-perfect one.

And do that – every election. Why not?

If parties refused to accept less-than-perfect candidates, then this essay would not need to be written. We would not live in the Douche vs Turd world – we would live in the Crest vs Colgate political world.

So – why are mutinies so rare? Well…

First, remember the timing. During the Ruling and Campaign phases, there is already a president/candidate leading the party. At those times, all other party members are subordinates. They must support their boss. (In fact, if they don’t do as they are told, then the boss can [and should] fire them). This leaves only the Pre-Campaign. Early on (in the Pre-Campaign), we have yet to select our candidate. Prospects [in the internal venue] don’t know [1] who will win, so they don’t know [2] if a mutiny is needed, nor [3] if they want to participate, or not. Only very late (in the Pre-Campaign) is the Candidate actually chosen (at the very end). So – a mutiny can only take place once: at the very end of the Pre-Campaign.

Second, criticizing any prominent party member, ever, is risky! If they go on to win the nomination, then they’re your boss. If instead they lose, (or are not chosen), then it was a moot point! What did you get? Nothing. The party lost (and is out of power), so… nothing was in it for you. How did you uniquely benefit, from speaking out? (You didn’t.) Therefore, if you hate the front-runner, then the smart thing is to criticize anonymously. Or – just hope that other people do the criticizing. Why lead the charge, against the front-runner? Criticizing a partly leader, is the ultimate Selfless act – helping the party win, but harming your internal career.

That is why mutinies are so rare. Almost always it is a replacement Candidates who initiates a mutiny. For example, Dean Phillips first criticized Biden (hoping to replace Biden as party leader) – but too early. His mutiny failed, harming his career1. In contrast, Kamala remained loyal to Biden, so –as Biden was getting kicked off the 2024 ticket– he handpicked Kamala as his replacement (rewarding her, and harming all the others). (More on this later.)

G. Summary So Far

Let us review the facts we have gathered so far.

- On election day, the voter has only two choices – the 2nd choice is his only recourse, should the 1st prove deficient. So, whenever a party makes a mistake, it harms itself (of course) – but it also harms us all. It unilaterally puts the rival party on a longer leash – thus allowing them more transgressions. It diminishes the professionalism of the entire competition. It increases the “corrupting influence”, because now a terrible rival candidate [who fights their way to the top], may actually win the general election – despite being terrible.

- Only during the Pre-Campaign, can we optimize our candidate. Once someone is chosen as Candidate, it is too late to replace them. Once both Candidates have been chosen, criticism can only take the form of Electoral Defeat. No sane party member would ever criticize their own Candidate – they would never contribute to their own party’s defeat.

- During the Pre-Campaign, we cannot expect senior party members, to be criticized appropriately – by anyone. First, they will not criticize themselves. Second, their subordinates will not criticize them, either (which is a shame, because subordinates probably know more about the candidate’s shortcomings than anyone). Third, the rival party has backwards incentives: they are hoping that the worst candidate is picked – since they do not want to face off against a strong competitor. (Thus, the rival party will be actively sabotaging our Pre-Campaign, hoping to trick us into choosing a terrible candidate.) Therefore, the senior party members will have their known flaws concealed, by almost everyone – an example of the corrupting influence.

- [As Boss Tweed implied] – winning the Candidacy is probably much harder than winning the General Election. After all – in the general, one of the two candidates is guaranteed to win (so the baseline is 50% likelihood). To win the Candidacy, you must defeat many competitors. Furthermore, the general election is complex and unpredictable – and affected by many people, including donors, and the base. It therefore absolves you of [some of] your mistakes. Not so in the nomination race – when you are expendable. If you lose the general election, you still have influence and name-recognition. So – the Candidacy is actually the Big Prize, and politicians adjust their effort accordingly: desperately cutting deals, to secure the candidacy for themselves, even if it makes their administration (or campaign) worse.

The good news, is: in order to reach our goal (that being: two good choices on election day), we really only need to fix one party. As soon as one party steps up its game, the rival party will have no choice but to follow suit.

The bad news, is: the parties have a natural tendency to feed off each other’s malice. Any errors made by a party – any corruption or incompetence – even if introduced accidentally, or from bad luck, or the mere passage of time – these deficiencies will corrupt the rival party. A weak competitor, (a “safe” district2), shifts politician’s concentration from the external venue (general election) to the internal venue (candidacy/primaries).

Our worst case scenario, is: when politicians pour all their effort into the nomination. In that case, we will always end up with two awful candidates, battling it out in the general election. Both bad candidates sleep soundly, knowing that –since they are both awful– they both have a solid chance at winning, and their awfulness does not disqualify them. On election day, we voters, begrudgingly, pick the better of the two – and then we repeat this meaningless process, in four years.

Now… back to our original question: who’s responsible for this mess?

Why are the two choices on election day so bad?

H. Crossing Over

Paradoxically, one party’s awfulness will “cross over”, and infect the other party’s candidate-quality.

My rival should be strong to keep me sharp!

-Gary/RIVAL, Pokemon Red/Blue, 1996

A lazy candidate-selection-process –ie, the low-quality Pre-Campaign– is harming not only that one party, but also all citizens of the country. One weak competitor, means that both candidates are put on a longer leash – both can be more corrupt – both parties can enrich themselves, whilst fleecing the common citizen.

After all, the population can be first divided [“left” vs “right”] (of course, as we all know), and then second, divided again: “party elites” vs “common citizens”.

. | Left | Right |

Party Elites | | |

Common Citizens | | |

In one sense, separation is healthy. “Registered Republicans” should go off, and form their own club – [ie, their own party]. It should have its own structure, and hierarchy, and membership-criteria. Adversaries (ie, the Democrats) should not be allowed in – and they definitely should not be allowed to tamper with the Republican candidate-selection process. (That would only invite sabotage.) So, in that sense, the parties must separate.

But, in a different sense, they are inseparable. All common citizens —left and right alike— have an inalienable right, to two high-quality choices on election day. If deprived of that, then “the people” –aka the commoners [of both parties]– are harmed. Thus, the commoners have a right to lash out – to vindictively destroy something. Retribution is not only fair game – it is in fact an ethical imperative. We must balance the scales of justice. “Mercy to the guilty, is cruelty to the innocent” [Adam Smith].

Today, we get no such justice. And that is why the two options are so bad. The bad candidate-chooser, does not feel enough suffering.

Paradoxically, the candidate-chooser of the losing party, is to blame, for all uncorrected imperfections in the whole government. After an embarrassing defeat [on Election Day], we citizens (correctly) blame the losing party for having lost. But we don’t blame them enough. We don’t blame the losing candidate-selection process, for how bad the winning party’s candidate was. We don’t blame them for lengthening the leash!

If a party is run poorly, then their own leadership is bad. But – if a party is run poorly and wins – then the other party’s leadership must be even worse! After all, it is their job to exploit the other’s mistakes.

Thus, errors can be handled in two opposite ways. The first way, is healthy: a party [1] notices that its opponent-party has screwed up, [2] takes this information to the voter, and [3] converts it into an increased chance of winning, and [4] wins the election. The second way, is unhealthy: a party [1] notices that its opponent-party has screwed up, [2] converts this to an increased chance of winning, and [3] trades away these surplus percentage points, for some selfish and/or corrupt gain, [4] thus re-harming their own party, resulting in [5] an election that is closer to 50-50.

That second way I call crossing over. One rotten apple, corrupting the other. On and on in a big spiral.

I. Outcomes

After all, voters want outcomes – not candidates.

The candidates, (and the parties, elections, slogans, SuperPACs, etc), are all just by-products (necessary ones) of the citizen’s struggle to persuade the government to work toward certain outcomes.

For example, the closing of Guantanamo Bay, was an outcome that Obama-2008 promised to bring about, during his campaign. Obama won, but reneged on this promise – outcome NOT achieved. Who is the victim? The people. After all, “the people” voted for it to close.

Candidates mean nothing, outcomes mean everything. For example, imagine that [back in 2017] Obama and McCain both revealed – that (!) each was actually the other, in disguise, the whole time. We thought that Obama was in the White House 2008-2016, but it was actually McCain. McCain had craftily dressed up as Obama, appeared on TV as “Obama”, and implemented Obama’s political agenda. I ask: what difference would this make, to the residents of Guantanamo Bay? They are still stuck there! What matters is if Gitmo stays open or not – everything else is a pure ad hominem fallacy.

Back in our real world, in 2012, Obama won reelection. On the Gitmo issue, Romney failed to hold Obama’s feet to the fire. After all, if Obama broke a campaign promise already [even a single one], after winning a super-majority in the Senate and House – then why would anyone believe any of his campaign promises in 2012? This lack of credibility, is quite a gift to Romney – but Obama needent have worried. Obama-2012 won anyway. (And [for better or worse] Gitmo is still open, to this day.)

Could things have gone otherwise?

Well, what if the 2012-Republicans had run a hyper-optimized Pre-Campaign and Campaign? They would then field a Perfect Candidate – who would (among other things) criticize Obama for breaking his Gitmo promise. Perhaps, Obama could have lost, in this world. (After all, it is tough to beat a perfect candidate.)

But that only scratches the surface, of the logic that I wish to explore.

J. Time Travel

Let us now ask: would Obama have behaved differently, if Obama knew that –from this moment on– Republicans will always run hyper-optimized campaigns only?

Back in 2009 [his first day in office], Obama might try harder to fulfill all his campaign promises. After all, to fail would give the Republican party ammo against him. So – Obama might have closed Gitmo after all! Obama would achieve the outcome purely out of fear [his own selfish fear] of losing the 2012 election (in four years).

So far, so good.

More interestingly, we might ask: during the 2008 campaign [before Obama was even in office], would Obama have still promised to close Guantanamo Bay, in the first place? Maybe Obama would have thought harder, about if it was a promise he could keep. He would have to weigh the [1] “easily duped” voters he could get today, against [2] all of the “long memory” voters he would lose in four years. Furthermore, right now, the hyper-optimized Republican campaign, might call him out on making such un-keepable promises. So, Obama would tend to become more truthful – from the first moment of his campaign.

Thus, as the losing candidate becomes stronger, they radiate honesty and virtue, into the winning candidate, both forwards and backwards in time. (An example of the long leash.)

K. The Cross-Party Blame Game

Thus, a voter who was swindled out of an outcome they voted for (ie, to close Gitmo), could blame:

- Obama –obviously– for not living up to his promise.

- The Republican Party, for being so inept at running campaigns – thus decreasing Obama’s fear. Ie, decreasing Obama’s motivation to proactively shield himself from criticism. In other words, decreasing Obama’s motivation to do a good job.

So – we are making some progress. However, what does it mean to say: “in 2012 the Republican Party was inept at running campaigns”?

It means: the candidate-chooser knowingly failed to optimize their choice. They were negligent in their research [of the prospective candidate’s flaws]. So I will now discuss the problem of maximizing our knowledge of each candidate’s flaws. Maximizing our search for the Optimal Candidate (ie, the one with the fewest flaws).

L. Internal Motivation <– External Discipline

Imagine I know that I’m doing something wrong. My wrongdoing can end in two ways:

- internal – I can decide to stop; or

- external – I can continue to do evil things, thus having a negative affect on the people around me – they will eventually [1] stop trusting me, [2] seek revenge, [3] gossip about me, [4] report me to the police, [5] declare war, etc.

The first kind is better. I know the most about my situation – in that sense, I am the best judge of it. (Adam Smith called this the “internal witness” or “impartial spectator”.) Self-criticism is the most accurate kind – but it has an obvious principal-agent problem. Why would I ever punish myself?

And so – what is the best way of achieving self-criticism?

Jeff Bezos tells a story about his determination to provide fast customer service. Internally, it seemed as though service was adequately fast – but this was an illusion. Bezos broke through the illusion, by picking up a phone, and calling Amazon’s customer service number himself – exactly as an external (customer) would.

This external discipline, is the best way to reward people for being proactively self-critical. Bezos knows, that customers can take their business elsewhere – this is external discipline. Similarly, he knows that Amazon shareholders can dump the stock on a whim. This is the paradigm Exit-Voice-Loyalty which emphasizes this fact: the cost of exit imposes external discipline, and thus inspires proactive self-criticism.

Bezos could instead be lazy – and Amazon would fail, eventually. After Amazon failed, Bezos could lie, declaring: “It was just bad luck! I did everything I could to save Amazon!”. This would be untrue – but how could we prove it? On what grounds could we contradict Jeff Bezos? After all, he worked there full time – he was the CEO and knew all the key issues. How do we know, whether or not Bezos “did everything [he] could”?

M. Strict Liability

Legal theory has different “categories of harm” – including one called “strict liability”.

Statutory Rape is a member of this category. You are not permitted to say (for example): “I had no idea – she told me she was 18!”, etc. The reasoning, is that this gives citizens a strong incentive to investigate the truth beforehand. It makes citizens more responsible. They are held accountable to the outcome. If any sex-with-minors occurs, then the adult knows that blame is going to be nailed back, onto them.

We cannot expect perfection from either party – just as we cannot expect perfection in toothpaste. But we can insist on self-criticism. We can insist that parties investigate the truth, and root out all known flaws, [in their candidate and platform], during the Pre-Campaign.

In other words, we must treat Pre-Campaign failure as statutory rape. Although the two phases (Pre-Campaign and Campaign) are different (as I explained in Part 2), they hinge on the same outcome: losing the general election. In the same way, toothpaste-makers are punished for losing the sale. It doesn’t matter if the product is bad (pre-campaign), or the marketing is bad (campaign) – both are punished – both are held accountable to the outcome.

This may seem harsh. After all, even in a perfect world [where both political parties try their very best], one party must lose. It seems wrong to punish perfection. But it is not as harsh as it may seem – after all, it is the same harsh reality faced by Crest and Colgate every day. Everyone who ever competed for anything, runs the risk of losing. In a world with two optimal toothpastes, the customer will only walk out of CVS with a single tube. We want a ruthless sorting operation, an Olympic Gold Medal, taking only the very best – that is how we get continual improvement. That is what we demand from every person, at every job. The state-of-the-art is always improving – NFL Players, toothpaste, TV shows, software, golf simulators – expectations are rising every day. That is how societies progress. Parties should be held to the same standard as everyone else.

Fear of losing, is what keeps people motivated. If the Pre-Campaign is failing us, then we need to up the fear. And we need to focus it on the right people. This is our North Star: punish the Pre-Campaign process, if it fails to win the election.

But – what does that mean? Who should be afraid – of what? What would they lose? And who would take it from them?

I will answer all that in Part 7.

But first…

Continue Reading: Part 5: Districts // Part 6: Independent Agencies

Footnotes

-

The DNC basically sabotaged this attempt, torpedoing his career. According to Andrew Yang, someone who merely did a favor for Dean Phillips was subsequently blacklisted by the DNC. A few others who were formers skeptics, later regretted it – citing the failure of the primary system, in fact (see part 8). ↩

-

Tangentially, see 2:04:10 of this video – “everyone in a leadership position, is in a safe district”. ↩