With a social theory of identity, combined with blockchain bearer tokens, we might achieve a realistic improvement over PGP.

Motivation & Scope

(Basics) Any private computer system implies the existence of identities. Without identities, privacy and most commerce would be impossible, and the web would be overrun by spam, Sybil attacks, and so forth. Fortunately, authentication (usernames and passwords) was invented, allowing individuals to control, and “own” a private slice of cyberspace.

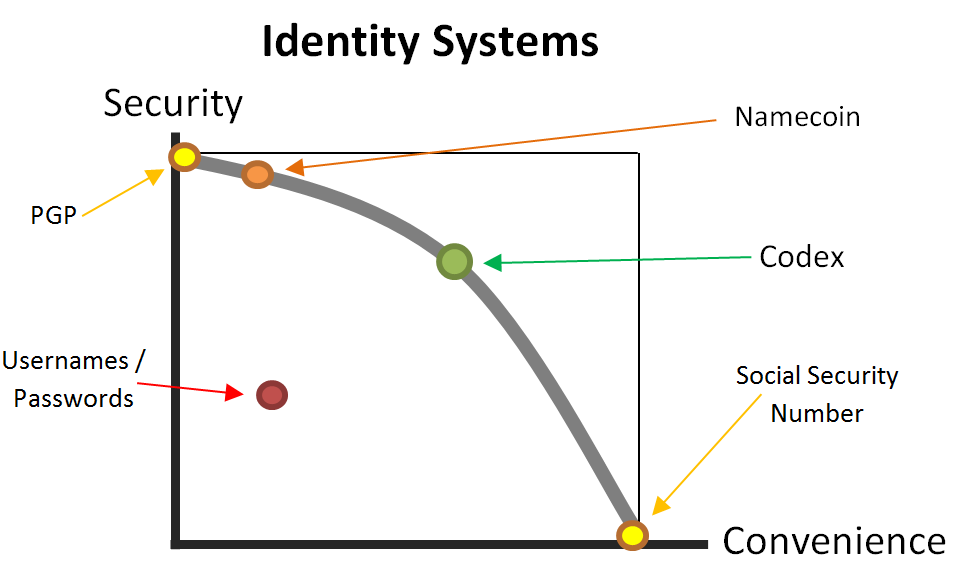

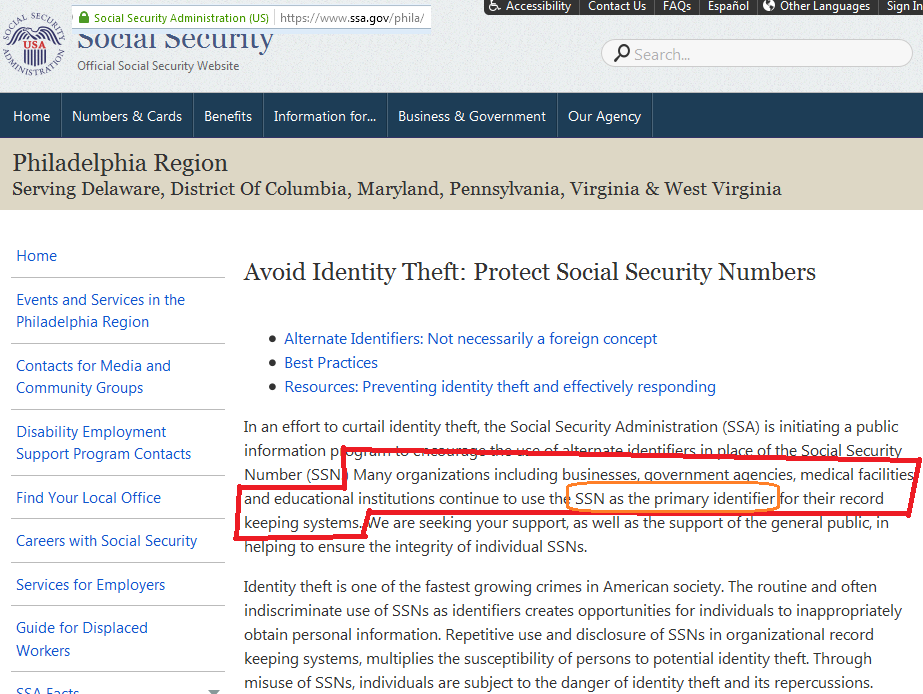

(Today) Many authentication methods are used today. They might best be arranged along a “convenience-security tradeoff”: On one extreme, Snowden used PGP, and insisted that his correspondents use it as well (despite their considerable reluctance). On the other extreme, all Americans today use their Social Security Number as an ID (and as a password) – it is used to file taxes, apply for credit, and fulfill civic obligations. The SSN is convenient because enrollment is free, automatic, and universal.

This project aims at neither extreme, and instead seeks an intelligent trade-off between convenience and security.

By the metric of “convenience”, the SSN is the most successful:

However, by the metric of “security”, PGP is the most successful. (As far as we know, the security is invincible).

Comparison Table

| Feature | PGP | SSN | Codex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forgot your password? (Reclaim lost ID). | No | Yes | Yes |

| Identities are “human readable”. | No | Yes | Yes |

| You own your identity – no administrator. | Yes | No | Yes |

| Utilizes modern cryptography (signatures). | Yes | No | Yes |

| Transfer identity to new crypto-key. | Yes | No | Yes |

This project DOES address these problems:

- Identity Namespace Collisions (Will the real “John Smith” please stand up?)

- Allowing a single identity to prove that it signed various things at various points in time (so as to facilitate reputation / credit reporting / Sybil-protection). This is superior to the “WoT strategy” of collapsing ‘reputation’ to a single dimension, because reputation is multidimensional.

- Users who pick insecure passwords.

- Security that scales with value.

- Password Reuse / The fact that passwords are used at all (when we could instead use signatures).

- Humans have powerful software in their brains already. This software has modules for (the meatspace equivalent of) ‘identity management’ and ‘identity theft’. However, this meat-software goes unused (mostly because the imposition of awkward passwords actively circumvents it).

- Competing standards (vs “something unique/inimitable about this standard, so that we can coordinate on one”).

- Corporations / Refrigerators can have their own “identity”, if you care about that kind of thing.

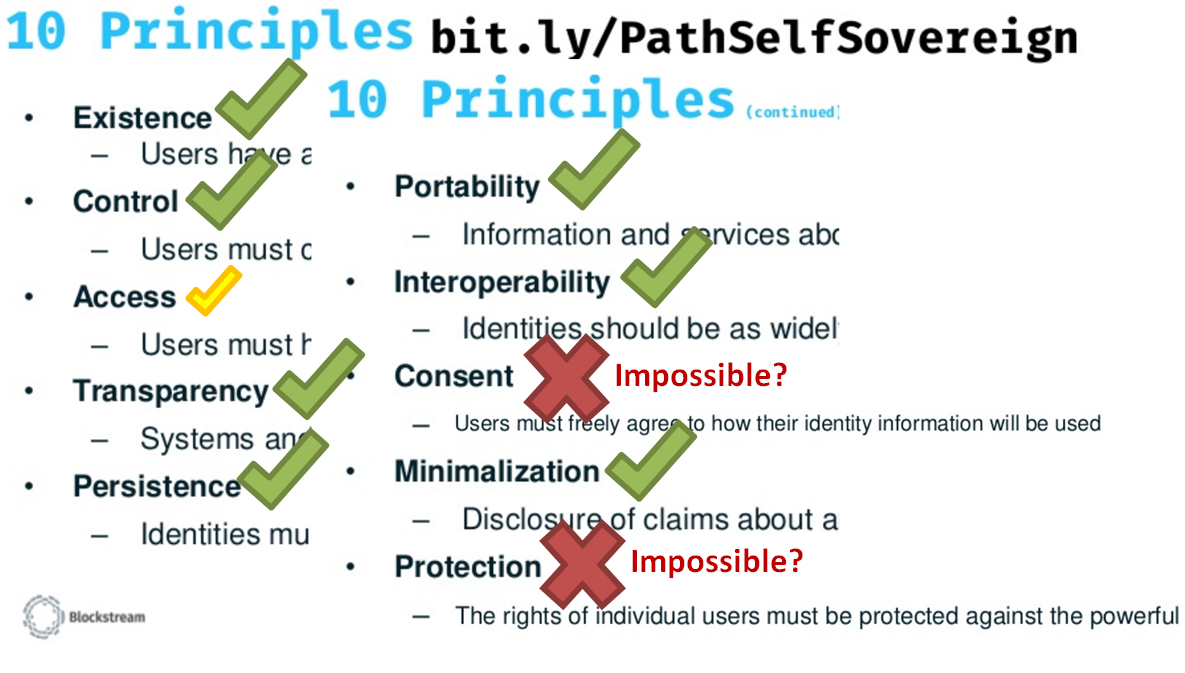

This project DOES NOT address these problems:

- Someone might learn my name, or my age or whatever…even if I don’t want them to! (This is a lost cause, thanks to Google / e-Verify / LinkedIn / Whitepages / the “database join”).

- How can we decentralize identity? (PGP already does this).

- How can we use unbreakable h4kk0r encryption to thwart The Man’s violation of our Freedoms? (Again, PGP does this already).

Design

Our design calls for a blockchain* which tracks and updates key-value pairs. Whereas, typically, blockchains are used to achieve decentralization, in this case one is used for security and uniqueness. For security: a single administrator cannot steal all of society’s most valuable identities. For uniqueness: the question of “Why should I switch to your ID standard?” (which is of immense practical importance) is met with the answer that this one is public. There are many ways of privatizing something (one per owner), but -per algorithm- only one public system.

*A merge-mined Bitcoin sidechain.

The sidechain is financed by transaction fees. The transactions are paid by users who wish to add or update entries to the database. Nodes are run by anyone who wants (or, for compliance purposes, is required) to verify identities “properly”. (Everyone else would just use Google’s node).

In general, the value proposition is that digital service providers (Facebook, YouTube, Disqus, etc) can replace several labor-intensive services with software. In particular, customer support tickets related to resetting accounts: either because the passwords are lost, or because accounts/identities were stolen. Moreover, the existence of a durable, long term, multipurpose digital identity may allow new services to be rendered (tiered Spam prevention, for example), and may improve existing services (encrypted email, accurate routing of payments, secure filing of taxes, etc).

The identities are associated with cryptographic keys, and these keys are managed in a way similar to how humans use physical keys. Namely, on television show Seinfeld, the main characters all have copies of each other’s apartment keys, for emergencies.

In this system, entries are added with the form:

add_1( hash )

add_2( add1_hash,

name=(arbitrary 100 bytes, for example First, Middle, Last),

data_commitment=H(D),

Friends=(U1, U2, ...),

Weights=(W1, W2, ...)

)

The hash-reveal strategy is a well-known technique to prevent the front-running of commercially-valuable names.

With these commands, someone joins the network. They declare their name, and a set of friends (and weights for each friend) to be the guardian of their identity. This ID is linked to a set of cryptographic identifiers (4096-bit public key, bitcoin stealth address [reusable], BitMessage address(es), .onion address). All-in-one software may automatically generate keys, display private info (to be printed out or written down), and generate the appropriate CODEX message. It’s one stop shopping for a secure, private, Web 3.0 experience.

The actual data (“D”) is stored on larger, “full” nodes. Users only need to keep the identities of themselves, and their correspondents. Correspondents can share ID-data at any time; because it totals <1 KB, it can be included ahead of each email (or each payment, etc), and easily verified by nodes.

D = {

public_key : 512 bytes,

btc_stealth_address: 102 bytes,

bitmessage_address: 32 + ? bytes,

.onion_url: 16 bytes

}

Stealth reference. Bitmessage reference. Onion reference.

Blocks have UTXO commitments, such that “thin clients” can verify any ID-data which is sent to them. Thin clients will require storage/bandwidth amounting to ~8.4 MB / year (a trivial amount). Greg Slepak has argued that, for Namecoin-like projects (of which CODEX is one), Radix Trees may be an appropriate UTXO-tree format.

The database contains the following fields:

| Field: | # | Name | Sequence | H(D) | Friends | D* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bytes): | 5 | 100 | 3 | 20 | 50 | 572* |

”#” is the unique (and permanent) row-number, “Name” is an arbitrary 100 bytes of text, “Sequence” increments with each duplicate “Name” entry, “H(D)” is the RIPEMD-160 hash of the name’s cryptographic identifiers, “Friends” is 80 bytes for identifying and weighing 8 friends (5 bytes = 40 bits for “Friend #”, and 10 bits to allocate three digits .ABC). “D” is the cryptographic identifier data itself, which does not need to be held by anyone (but which will eventually be collated and indexed by Google, MIT, NSA and so forth).

The choice of 8 friends is quite personal, but it would be advisable to use three categories: friends, family, and co-workers. Users may even make a second “conservative self” account, whose rarely-used private key is granted extra security (kept in a safety deposit box, or itself broken/distributed through the use of a secret-sharing algorithm). In this way, “ownership” of the identity can be sufficiently decentralized.

Crucially, the user can ask their friends to ‘reset their password’, with:

reset( name,

new_H(D),

friend_data= (D1, D2, ...),

signatures = (S1, S2, ...)

)

For security reasons, you can not reset your own password (of course, you can set yourself as one of your “friends”, and give yourself great weight). The reset process prompts everyone with alerts (that the process is taking place), and advice about how to check identity properly, as well as latest tips for avoiding phishing / scams. For fun, the blockchain may report each user’s “shame score”, which is a count of how frequently a given user forgets his/her password.

Notice that the blockchain does not “know” any user’s public keys, including those of the friends. Friends must therefore send their entire “D”, which is parsed for a public key. This borrows from Gregory Maxwell’s Namecoin strategy of pushing information into (larger) messages, which can then be deleted permanently. This allows a lighter UTXO load, even if it requires bulky messages (which is highly desirable, as UTXOs are a permanent externality whereas messages are mitigated by tx-fees).

To account for the ever-shifting landscape of friendship, each user can:

update( name, new_friend_#, signature, [old_friend_demote])

Which adds 5% weight to the new public key. This can only be done once per week. If 8 keys have already been defined, the one with the lowest weight is deleted (and the remaining seven are rescaled, such that they sum to .950). If new_friend_# already exists in the set of 8 friends, then old_friend_demote determines which friend loses the 5%.

Finally, for name-changing, we have:

rename( name, new_name, signature )

This can only be done once per year, and only if it survives a grace period (of one month). During this grace period, the user’s friends can cancel the name change. This is to protect identity thieves from forcing a user to adopt a false name for a year.

The “rename” function does not change the (unique, permanent) ID-#. By retaining it, users can retaining their account history. Alternatively, the user can simply create a brand new ID.

cancel_action( tx_id, friend_signatures = (s1, s2, ...) )

For commercial purposes, it may be desirable to “sell” an ID:

buy( name, new_friends=(#_1, #_2, ...), seller_btc_address, sell_price, buyer_unspent_output, buyer_signature, seller_signature )

This function transfers ownership of a name to an entirely new group of “friends”. In this way, the concept of “Walmart” can change ownership. This also requires a one-month grace period, during which the transaction can be friend-cancelled.

To be courteous, the seller may ask friends to “reset” H(D) to a value requested by the buyer. In this way, many things can be accomplished at once: the seller can notify friends of the intent to sell (and that they should not interfere), the friends can confirm the sale while updating H(D) immediately, and the buyer can “own” the identity immediately (upon confirmation from the friends).

( At this point, CODEX is functioning less like a self-sovereign identity, and more like a “PGP Market”. )

Other functionality is possible. For example, identity-theft “alerts”, which are broadcast for a fee and which alert id-checkers to be extra diligent.

Why Use a Blockchain?

The year 2016 has seen -without question- the worst blockchain designs ever presented. Given the overwhelmingly low idea-quality, I feel the need to justify my use of the blockchain in the following four ways:

1. Self-Sovereign Identity

Self-sovereignty is seen as a desirable (if not essential) property of a digital identity – each individual is the source of their identity. Blockchains faithfully execute pre-defined rules; they are inherently public and have no owner. Thus, a blockchain may be the only data structure which can meet the sovereignty requirement.

Otherwise, your identity will be “owned” by someone else (Facebook, Government, etc.).

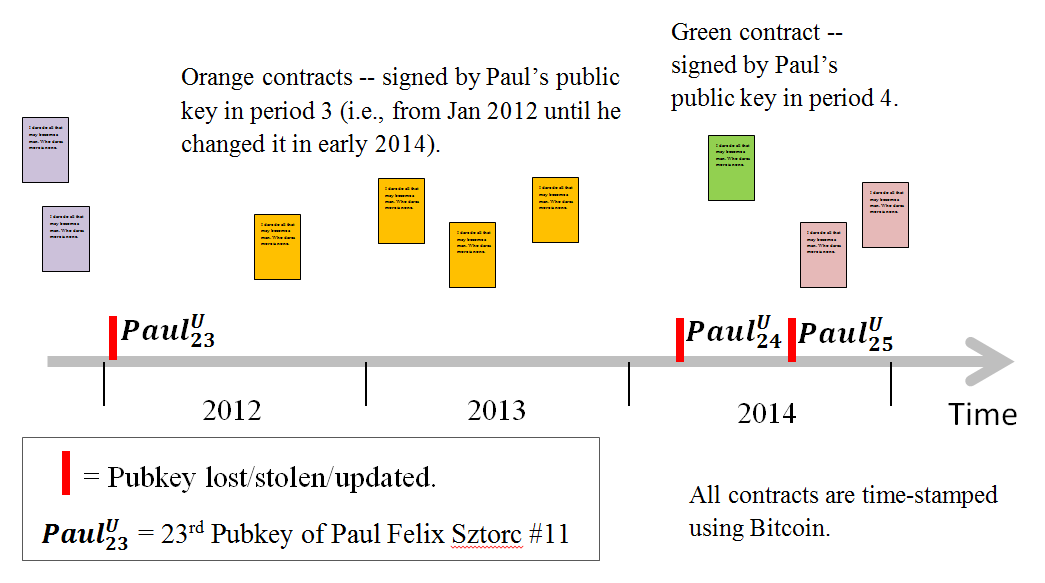

2. Historical Unity

The blockchain system tracks all messages – one hundred percent. It therefore, tracks a complete history of each “coin”, and this is potentially very useful for identity (see “Proof Diagram” below).

3. Use-Externalities

“Names” are one of the three use-cases of a blockchain I identified in 2014. These use-cases mirror the blockchain’s structure: a system where I have an inherent need to track the assets of other people.

4. Scaling Security

Blockchains prevent a situation where a few (pre-defined and locate-able) individuals have complete control over an entire system. As the system gains value, theft and/or malfeasance becomes inevitable.

Use Cases

- Unique IDs

- More private than SSNs (“we need the last four of your social”)

- Helps even with paper forms:

- Filing Taxes

- Voting

- Jury Duty

- Better Logins (Potentially, for All Websites)

- Standardized Login Process

- Use of Signatures = more secure.

- (with timestamping) Monitor every cyber-action taken by your employees.

- Positive Proofs – Ie, prove that “it was you” who signed those contracts (which were so fulfilled)

- employment contracts / sales contracts (for self-employed / contractors)

- I hired this person.

- This person terminated employment here, in a professional way.

- debt / mortgage / etc

- sales purchases (credit card purchases / bank checks)

- arrest record / background check

- employment contracts / sales contracts (for self-employed / contractors)

- Assertions

- “I claim, under penalty of perjury, that I am…<at least 21 years of age>”.

- <citizenship, residence, physical appearance, etc>

- (These attestations are not “on the blockchain”, which is ideal).

- Spam Control

- Filter accounts unless someone is using a name that was registered <more than 1 year ago>.

- (Account ages would be as long as human ages).

- Payments

- IDs could be associated with “reusable BTC addresses” (aka Stealth Addresses), giving users their own bank. If so, Bitcoin “Vaults” may assist with time-locked security.

Proof Diagram

Notice that, if a private key is stolen, the attacker cannot forge past contracts. This is because forged contracts will have the wrong date (they will not have been inserted into the Bitcoin blockchain at the appropriate time).

After IDs are reset (using the social mechanism), contracts would automatically be “retroactively unsigned”.

Conversely, if keys are misused by their current owners, then cryptographic proof of this misuse will exist permanently. For example, if “John Smith 28” signs thousands of contracts (each with different, mutually-exclusive wordings and conditions) and Tierion-timestamps all of these, he does have the option of picking-and-choosing desirable contracts -from this set- after the fact. In this way, he has the semi-power to backdate contracts. However, if these mutually-incompatible contracts are discovered (at any point in the future), blame can be cryptographically ascribed to John Smith 28.

In short, an attacker can do almost nothing with a stolen key. Contracts signed in the future will use a new (not-stolen) key. Contracts signed in the past were timestamped using the blockchain. Hence the magic: the blockchain provides a single, unique history for both the name and the key! This history is robust to a theoretically-unlimited number of changes-to/thefts-of either one’s name or one’s key. Such uniqueness, robustness, and guaranteed-longevity can only be provided by blockchain.

Full Node Costs at Scale

Total economic costs are unknown, but we can estimate one cost: storage.

Under the following assumptions:

- Three billion human users, and one billion commercial websites.

- No one forgets/sells their password, ever*.

- 5 bytes per # field.

- 100 bytes per Name field.

- 3 bytes per Sequence field

- 20 bytes per Hash Commitment**

- 50 bytes per Friend field.

We have 4 billion users * ( 5+ 100 + 3 + 20 + 50 ) bytes/user = 712 Gigabytes.

A 1,000 GB hard drive costs roughly 80 USD. According to Gallup, this amount is about 8 tenths of one percent of median household income.

*Recall that, unlike with Bitcoin, full nodes can permanently delete old messages. So message data is less relevant (vs. the size of the UTXO database).

**Bitcoin uses RIPEMD-160(SHA-256( Data )), to maximize forward-security as well as compression. The Commitment is 20 bytes.

Finally, recall anyone can verify an identity using a “thin client”. These clients have very reasonable resource-usage (can easily be run on a smartphone, etc). Identities can be shared/verified, even if both individuals are using thin mode. Anyone with a private key(s), can derive the corresponding public key(s), and RIPE(SHA()) them.

Trustless Buying of Identify-Verification, Offchain

What if Alice would like to send a message/money to Christopher, but Alice doesn’t know his Bitmessage Address? Even if Alice runs a full node, she can only learn Christopher’s H(D). Chris’ registration information is old (>6 months), and has been long since erased.

Firstly, charity may solve this problem. “Superfull nodes”, which track/remember, all raw “D” records, may provide this information, gratis. This larger database consumes a mere 3 terabytes of storage space, quite affordable to the likes of Google or MIT.

However, if no such gratis service exists, private “superfull nodes” are possible. For a known H(D), the D can be sold for BTC, and this can be done near-instantly, off-chain, and entirely without-trust. If Alice wished to buy datum D, corresponding to “Adam Smith the 3rd”, and Bob wished to sell it, one protocol would be as follows:

- Alice requests “Adam Smith - 3”.

- Bob replies with proof that the current record for “Adam Smith - 3” has H(D) = h*.

- Alice verifies the proof, and knows that Bob can, in fact, sell Alice what she is looking for.

- (Let us assume that Alice and Bob already have a LN channel open, and that it is currently paying 90 to Alice and 10 to Bob).

- Alice and Bob agree that the price of the data should be “1”.

- Alice proposes a new LN transaction, with three outputs. The first two are standard LN items. First is the refund to Alice – as always it has two possible conditions: [1] 89 to Bob immediately and [2] 89 to Alice timelocked. Second, is Bob’s refund: 10 to Bob immediately. The third is new, and it has two possible conditions: [1] 1 to Bob immediately, if D is provided such that H(D) = h*, and [2] 1 back to Alice timelocked.

- Bob signs Alice’s new LN-transaction, as it allows him the possibility of selling D for 1.

- Alice invalidates her previous LN transaction. Her situation has not worsened – precisely as before (should Bob disappear) she has 90 BTC returning to her post-timelock.

- Bob proposes a new LN transaction set on his end. It has three outputs: 10 to himself timelocked (etc), 89 to Alice immediately, and a novel third output. This output either [1] pays 1 to Alice timelocked, or [2] pays 1 to Bob immediately if D is produced such that H(D) = h*.

- Alice signs Bob’s new transaction. Bob invalidates the transaction which preceded it.

- They jointly construct yet another transaction pair, with the channel paying 89 to Alice and 11 to Bob. They each sign, but do not yet invalidate their previous transaction pair.

- Bob reveals D to Alice. To save on time, and on transaction fees, Alice and Bob invalidate the pair established in steps 6-9, and move to the tx-pair of step 10. The transaction is complete.

A more curious puzzle the monetization of step 2. At the SPV level, there is a tremendous difference between “BTC payments to you” and “ID-record proofs”. As time passes, a merkle proof of payment becomes more valid, yet an ID-record proof becomes less so. In this way, the mobile phone of “Adam Smith - 3” can NOT remember a proof of Smith’s identity.

Fortunately we can introduce an OP code, OP_HdToName, which we can substitute into the algorithm above.

OP_HdToName evaluates the top stack item, [Hd], and returns a value [Name] (which is the lookup, at the current block). Thus, one can “purchase” an identity-lookup using a script of the following form:

OP_HdToName [Name] OP_Equal

…which will evaluate to TRUE, for anyone who can supply “scriptSig” with the correct [Hd]. This script can be wrapped in the traditional OP_Checksig script (as required in steps 6 and 9).

In this way, full nodes can “sell” ID-lookups. This has the added benefit of correcting some of the “full node externality” – when the quantity of full nodes falls, payments to nodes will rise (on a per node basis).

Problems

1] Miners might just censor updates from people they don’t like.

Not really a problem, because the database doesn’t need to be realtime interactive…as long as the current database-state exists, anyone can look up a (Name, Pubkey) pair. Since they have the current pubkey (and since the pubkeys rarely change).

For the duration a 51% miner-coalition is in control, however, victims will not be able to change their Name, Public Key, or Associates. So, for them, convenience has temporarily degraded to the PGP level. Nonetheless, they retain any identities they possessed before the attack began.

2] Friendship Drama

“The whole world will know that we’re not best friends anymore!””

Yes, yes. Very tragic. Choose family, or co-workers for this reason, then.

3] “Now they know who to torture/blackmail!”

First of all, if adversaries were going through with physical capture and torture, they probably willing to put in the comparatively small effort it takes to to locate ones friends. In other words, they knew anyway.

Secondly, they need 50% of your friend-weight (and, they need them at around the same time). If you choose a large enough quantity of friends, and/or individuals who are geographically distributed, then crime against the group as a whole becomes more difficult.

4] This is putting too many eggs in one basket! Once an attack gets this key, they’ll get into all of my stuff!

Not necessarily. Even if this Identification method becomes widespread, to the point where it becomes the “single sign on” for the internet, it does not necessarily need to replace all the security features of, say, gmail. For one example, most websites today use two factor authentication. A second example: most websites track the physical devices which connect to their servers for authentication. Google will often ask you to “add a device” if your device is unfamiliar. Meanwhile, it will notify you about foreign devices which are claiming to have you behind them. These practices could (and should) persist.

5] My mean “friends” stole my identity and won’t give it back!

The individuals you “chose” are not your friends! Create a new identity and start over. Children should have their parent’s / parent’s friends as the ID-resetters. The elderly might use their own children as the resetters.

Alternatively, sue them for identity theft. (It’s not like you don’t know where to find them.)

6] I’m very unpopular and/or too paranoid to trust friends.

Use PGP. (And, don’t forget your password!) Or, use your lawyer.

Appendix

Theory

What is an identity? I argue that: Identity is social.

Identity, in a practical sense, isn’t individual – I already know who I am…and I always will. If I become someone else, through brain damage, then it won’t really matter if neo-I gets a new identity, will it?

Let’s address the problem which digital identity might solve. Imagine I get the following email:

Dear Paul,

I am "Francis Bacon". Please reply at your earliest convenience. But, beware! Lots of people are going around pretending to be me, via email! Don't trust them and don't reply to them.

Sincerely,

Francis

And further suppose that I receive a nearly identical email from someone who also claims to be Francis Bacon! Now I have two emails with contradictory claims. How would I tell which Francis Bacon is the “real” one, especially if I had never met him before?

Well, I might rely on other people who had known Francis. I might call his parents, or work colleagues, and ask them for their opinion – “Which email address is the right one?”. This is likely to be sufficient evidence.

Choosing Unique Identities

The entire point of a name is that it distinguishes “you” from “not you”. Thus, the sharing of names is undesirable.

Historically, names have achieved uniqueness in several ways:

- Leonardo “da Vinci” (place of birth)

- Adam “Smith” “(b. 1723)” (family name, year of birth)

- “King” Henry “VIII” (unique title, numeric sequence)

Most of these would appear to be discriminatory:

- Age (in most cultures, it is impolite to be compelled to reveal this – for women in particular)

- Place of Birth (may be a basis for discrimination)

- Job Title (titles of nobility are inherently anti-egalitarian)

In fictional world of “Game of Thrones”, identities and names (particularly family names) are of preeminent geopolitical significance (even, mortal significance). A character introduces herself as “Daenerys Stormborn, of House Targaryren, First of Her Name, Queen of Meereen, Queen of the An…Breaker of Chains, Mother of Dragons”. This introduction uses, in order: “given name”, “weather conditions at birth”, “title of nobility”, “family name”, “numeric sequence”, and “job titles / resume”.

Since job titles are transient and transferable (as are titles of nobility), it would seem appropriate to establish the identity first, and only later link the identity to titles and achievements.

It would seem that:

<First> <Middle> <Last> <Sequence>

…is the most appropriate naming syntax. With geographical partitioning automatically occurring (as an consequence of names in different languages). Some cultures, like the Chinese, have no middle name, However, new traditions are emerging (where Chinese adopt an additional Western given name, so that they have three total). On the other hand, some cultures have more than three total names. These can be all ascribed to the “middle name” slot, subject to a character limit.

The use of three names makes it less likely that the ‘Sequence’ field will leak information about the individual’s age. The

The proper encoding of names is, to me, unknown. Capital letters may be unnecessary (the convention being universally known), yet international characters (for example, the Spanish tilde) would certainly be required.

For the sequence field, two bytes (up to 65,536) may not be sufficient. The current most-popular US name has a frequency of nearly 40,000, and the (first) name “Muhammad” is apparently shared by 150 million individuals worldwide. Three bytes should be sufficient.

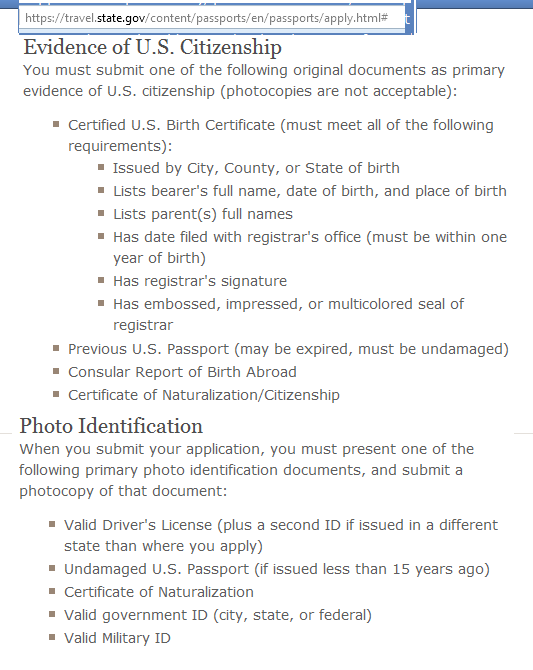

Establishing Identity in the Real World

To get a passport, one must bring other identification documents (from a predefined list). There is, hence, a principle of “redundancy” as well as one of “circularity”.

In addition, there are still penalties for attempting to subvert the document-issuance process. Those who sell fake ID may spent a considerable time in prison.

We have three principles: redundancy, circularity, and punishment. Redundancy and Circularity have simple software-parallels (multiple ways to reset or reclaim an identity, all of which are distinct but related to each other). Punishment is more difficult.

Getting There From Here

Often, switching costs can prevent a good idea from being used.

Some factors which may provide a “ramp” to adoption include:

1) Import PGP

PGP is useful, and used in the real world. We can start the Codex ‘Genesis Block’ as one which includes all PGP keys (on the MIT keyserver, for instance). These users can then start “adding friends”, 5% at at time.

2) Large Profile Hacks

As time goes on, a new generation of children will mature. These will be sophisticated tech-users, and will be cognizant of the adversarial security environment as well as government spying, schoolyard pranks / peer-competition, etc.

comments powered by Disqus