If anything, firms (not users) might use “private blockchains” to communicate with their competitor firms.

Intro

Interest in blockchain technology enjoyed a meteoric rise in the year 2015. Unfortunately, due in part to the secretive and informal nature of blockchain expertise, most interest has been misplaced or poorly-executed. If investments in ‘private blockchain’ technology are going to be made at all (which is dubious), they should at least be done right. I propose a new blockchain design: the “peer database”.

Caveats

It is easy to imagine a world where Private Blockchains are never used by anyone. Indeed, the whole affair could easily be a grave misunderstanding, and the concept itself might even be a walking contradiction.

But if they’re going to be done, they might as well be done right. In this post I will describe a “private blockchain”, as well as –and this is the real show-stopper, folks– some applications.

( I challenge you to find me anywhere else, on the whole internet, where someone advocates a “private blockchain” or “permissioned ledger” [or whatever abstraction-circus term du jour], and they also provide a concrete example of a use-case or application. Not some far-construal empty-suit buzzword like “settlement”, and actual guy today who has a problem. )

Attributes

- Private: Members can create/enforce rules for excluding the general public / specific people.

- (Optionally) Encrypted: This database technology can support data encryption, unlike Bitcoin (which does not).

- “Decentralized” / Peer-to-Peer (conditional on legal): With the exception of law enforcement (authorities, who can punish criminals and prevent tools from being used), no one has any more control over the shared database than anyone else.

- Immutability / Automatic Data Integrity: This database is as permanent as Bitcoin’s.

- Flexibility: Add whatever rules you want, change who can read/write/edit which parts of the database.

If you wanted a “private blockchain”, this is it. This is, probably, the only thing it could be.

Design Background

Since no private blockchain yet exists, we’ll have to just guess: what on Earth do these people think they want?

Expertise Vacuum

( I mean, who’s supposed to be the authority in this area? This guy? It would be nice if his well-researched posts synthesized into an actual conclusion somewhere [instead of R3 supper-song]. These two aren’t exactly brimming with confidence, are they? )

No offense, but we’re starting over, from scratch.

Privatization

When people say “this is a private event”, they usually mean that some people aren’t allowed. This implies the existence of identities, and excludability.

So, basically, we want to make it so that only a pre-selected few can read/edit the blockchain.

Blockchain Basics

The blockchain performs two operations on data: timestamping and verification. We will be hitching a ride on the timestamping part – its free.

Validation is harder.

Two Kinds of Validation

Trivially, data can be validated in two ways:

- By virtue of its uniqueness and/or context, it can validate itself. This works for high-entropy data, because it is impractical to create an exhaustive set of copies. Photos would work well, but a TRUE / FALSE boolean would not.

- A specific individual can attest to its validity.

( Bitcoin mining does a very clever version of the second: a “distributed membership multi-party signature” where there is an external cost to signing. )

With the first, the “private blockchain” problem can be dramatically simplified.

1. Using Half-a-Blockchain

It is possible to “use the blockchain” without creating your own blockchain. This is often the way to go.

Self-Validating Data: Anchoring

For ~free, anyone can use the blockchain to create an unforgeable timestamp.

There are firms which provide this service for you, for free. If the word “Bitcoin” skeeves you out, well, there are firms for that, too.

Data-validation can improve if everyone adds their signature to a block, whenever they can.

Anchoring Applications

- Legal Compliance

- Firm ABC is required to hold a certain amount of cash-on-hand at all times. This amount is a certain % of some other calculable value.

- Firm ABC anchors his accounting books at every opportunity, and publishes these anchors (either publicly –using twitter or Wayback or something, or privately, using the help of professional auditors).

- Firm ABC gets randomly audited by a an auditor / the government / a prospective investor. The auditor checks that the current books are valid. ABC gets a copy of the audit record.

- ABC has now placed itself in a position where all of their accounting books are likely to always be accurate. Books can be audited at any time, yet, the book-state is immutable.

- Now, Firm ABC cannot be accused of keeping two sets of books.

- Semi-Trusted Users

- Firm XYZ needs to rely on users for something – authentication, photos of a specific car accident. However, XYZ is concerned that their users will conspire to defraud them.

- Therefore, Firm XYZ requires users to timestamp self-validating data into the blockchain.

- Now, Firm XYZ can allow users to opt-in to great levels of data-proof.

Of course, on small scales this isn’t necessary. For example, consider a high school “young democrats” meeting where Jim thinks that Jane will edit the meeting minutes, after the fact (for whatever reason). These people can just use txt files in a free GitHub account.

Nonetheless, you could call this a blockchain. You could create a chain of blocks with this information and it might be useful to someone.

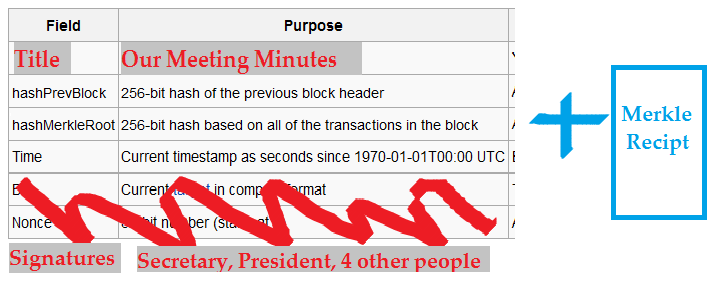

Above: Something that looks like a blockchain. Software can send around the these headers, and the data which comprise the chain’s blocks.

2. Peer-Validated – “The Peer Database”

When competitors need to work together, the may benefit from using a blockchain.

Now, we switch to peer-validated data. Here, I am going to combine the properties of “blockchain” and “private” as best I can.

Basics

As with Bitcoin, [1] database updates are placed into blocks, [2] those blocks are identified by unique hashes, [3] each block contains the hash of its single previous block, such that the “chain of blocks” has a deterministic history.

All blocks are anchored in the Bitcoin blockchain at every opportunity.

New Stuff

In a public blockchain, there is no concept of identity. Any dispute over “why database state is the most recent” is settled with proof of work (ie, the common signal of the “heaviest chain rule”).

Instead, we won’t be bothering the miners, because [1] they aren’t in our private club and we don’t trust them, and [2] we have no clear way of contacting them, keeping track of who they are, or motivating them effectively.

Instead, as before, we will just have everyone sign the database. The authentication is sequential (round-robin style), each person has a turn to propose a state, which he signs first and then sends around for the others to sign.

Or you can use PAXOS for all I care.

Protocol

The blockchain protocol is as follows:

- If everyone signed, including you, and the block was anchored, then you have achieved consensus. This is called a “unanimous block”.

- If >50% signed, but you didn’t get the chance to sign, your competitors may be cheating you, or it might be nothing. Follow these steps, in order:

- Wait for the problem to go away.

- Call your rival’s IT departments to ask them what’s up.

- Angrily renegotiate the bandwidth parameters of the database.

- Finally, if you continue to have problems, back out of this arrangement (and/or sue your trading partners for breach of contract).

- Equivalently, if only <50% have signed a chain with your signatures on it, the network may have forked and you might be on the losing side.

- Disputes over “which chain is longest” are settled by the following rule: whichever chain has the highest quantity of signatures, excluding any signatures from someone who has ever double-signed.

- Therefore, until you reach a “unanimous block”, you should consider the database not-up-to-date.

- Follow the steps above [2.1 through 2.4] if there are problems.

- Ignore any blocks that aren’t anchored.

There. That is as close to “private blockchain” as it is probably possible to get.

Since identities are pre-established, all of the latency/storage problems of the P2P network go away. Moreover, it is easy to implement arbitrarily complex business logic (including automatic-negotiations and other fancy stuff), including encryption (data privacy). It is even possible, since signatures are pre-defined, to ascribe blame to a particular individual (who “screws up” and signs something twice).

Since CEOs already need to sign their accounting statements, it is possible, in principle, to put someone in charge of signing a ledger (under threat of lawsuit).

This design mirrors Bitcoin’s (individual users would like to cooperate, but can’t trust each other to comply with rules).

Applications (!)

Warning

First of all, it is entirely possible that there a no applications. Blockchains might only be useful for digital bearer assets. After all, Bitcoin was a mechanism, and all mechanisms need money to fuel the mechanism. In the real world, the money is opportunity costs inherent to jail-time; in Bitcoin, the system prints actual Bitcoins for miners to use.

If disputes over database-state are to be resolved by proof-of-work, and not by courts/police/lawyers, what is gained?

Here are few guesses:

Specialization in Settlement

“Settlement” is a popular word, but few people explain where the value is created. Here is my attempt:

When a company exists to facilitate trust (exchange, settlement, escrow, dispute resolution), we might expect a Peer Database to help. The “data” pieces can happen in blockchain world, and the “physical” pieces are, then, freed up to become very “dumb”, and can blindly obey the database.

This enables specialization, and specialization usually adds-value.

For example: currently, the purchase of a train ticket can involve sophisticated software (databases, internet/cellular infrastructure, payment processing), but the train conductor only has to perform the single specialized task of “taking” the tickets.

In general, a great deal of exchange never even needs to settle physically – financial markets, travelers exchanging currency, or gift cards, or airline miles.

However, the obvious question is: won’t counter-parties still be able to take each other to court? Surely, the answer is “yes”; therefore, proof-of-work is not really “competing” and it is unclear if this will work.

Semi-Cooperation

Based on the structure of a blockchain, we would expect them to be used where “someone else’s data affects you”, but you don’t trust anyone to be in charge of a database.

So here are the only private use cases I’ve found so far:

A. Balance Sheet Externalities

Image that Bank A and Bank B compete against each other, and hate each other. However, they both work with Bank C. If Bank C (“Lehman Brothers”) were to disappear, it would be quite a job to figure out what exactly they owned, and who owed what to whom.

Perhaps, it would be better for a banking consortium to, selectively, keep track of some of that information. Perhaps, “too big to fail” banks might also ‘peer’ with regulators, or the bankruptcy court.

B. Supply Chain Efficiency

Gains in efficiency are possible with greater information sharing, but firms are often punished for the info they share.

A peer database can implement arbitrarily complex business logic and cryptography, and might therefore have a unique advantage as a data “cleanroom”.

Conclusion

I have proposed a “private blockchain” design which I call “the Peer Database” (although, in truth it is not dissimilar from Peter Todd’s tree-chains, proposed in early 2014).

It may be useful when competitors would like to work together.

comments powered by Disqus