[Within a given protocol,] miners don’t really control anything.

I used to say that miners could only do a few bad things:

- Censorship

- Reorganizations (51% Attack)

But now I doubt even the first of those. If we stay within a given protocol, at any rate.

In contrast, since the soft fork asks miners and users to change protocols, there may be “censorship” of transactions. But this is what blockchains are designed for! Satoshi’s Bitcoin “censors” double-spends and invalid txns. Information cannot become knowledge unless it covaries with some other pattern (which implies the compliant info needs to be “promoted” and non-compliant info needs to be “demoted”).

Blocksize Economics

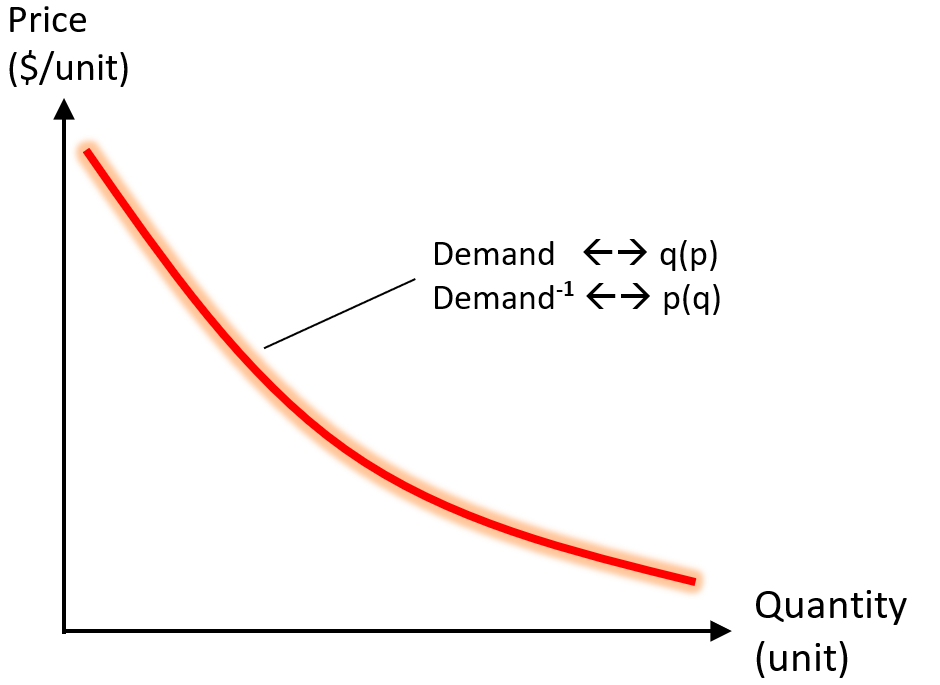

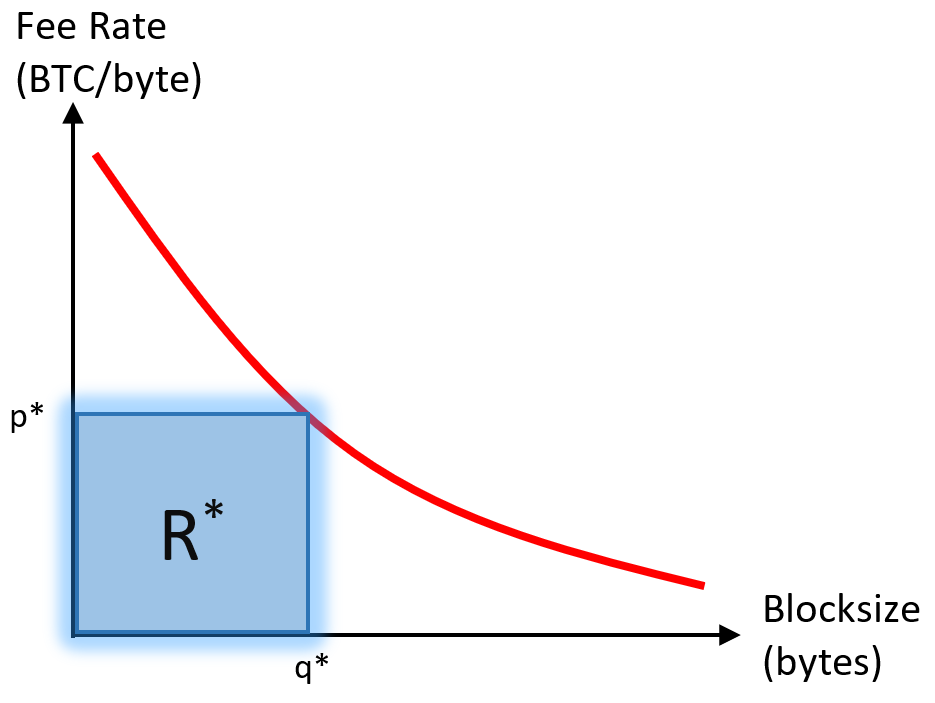

For a given demand curve (p(q))…

…there exists some Q that maximizes R(q) = q * p(q).

q* = argmax_q (r)

As I have presented before, miners should be able to estimate q* and enforce it on other miners. While miners may not know the shape of the Demand Curve (aka p(q)), they should be able to estimate it accurately. From p(q) they can calculate R(q) and therefore q*.

Once we know the q* for each block, we also know each R.

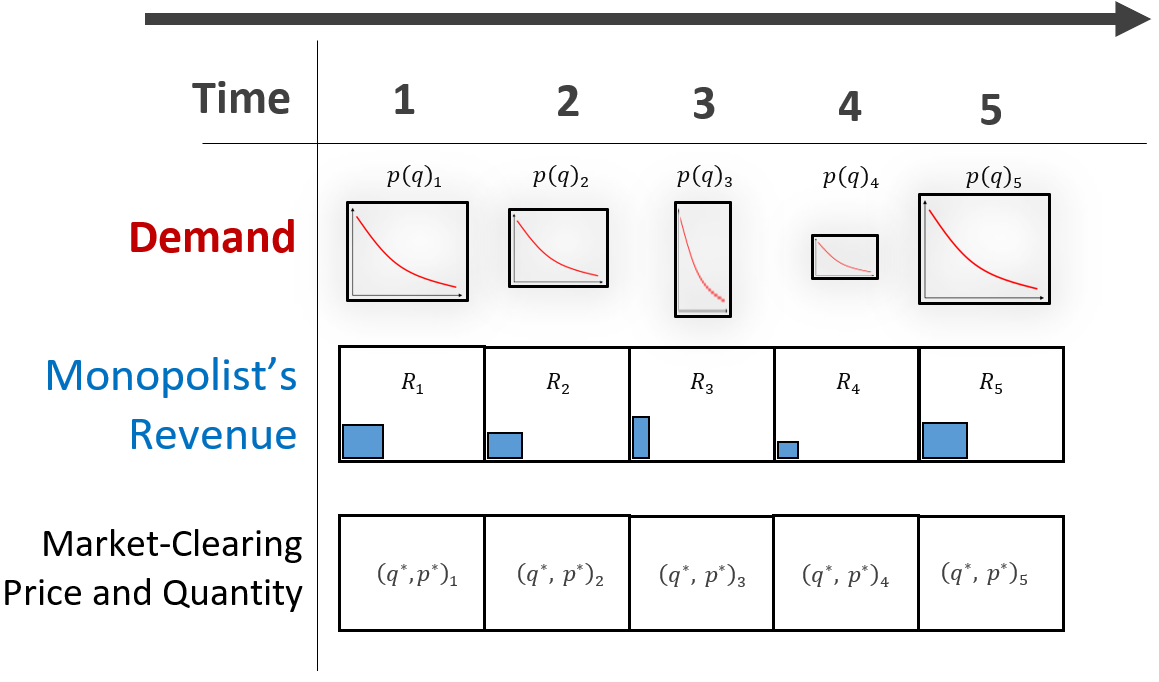

For a given history of demand curves (ie, for a given history of mankind), this is all objective information.

Altering History (And Therefore Demand)

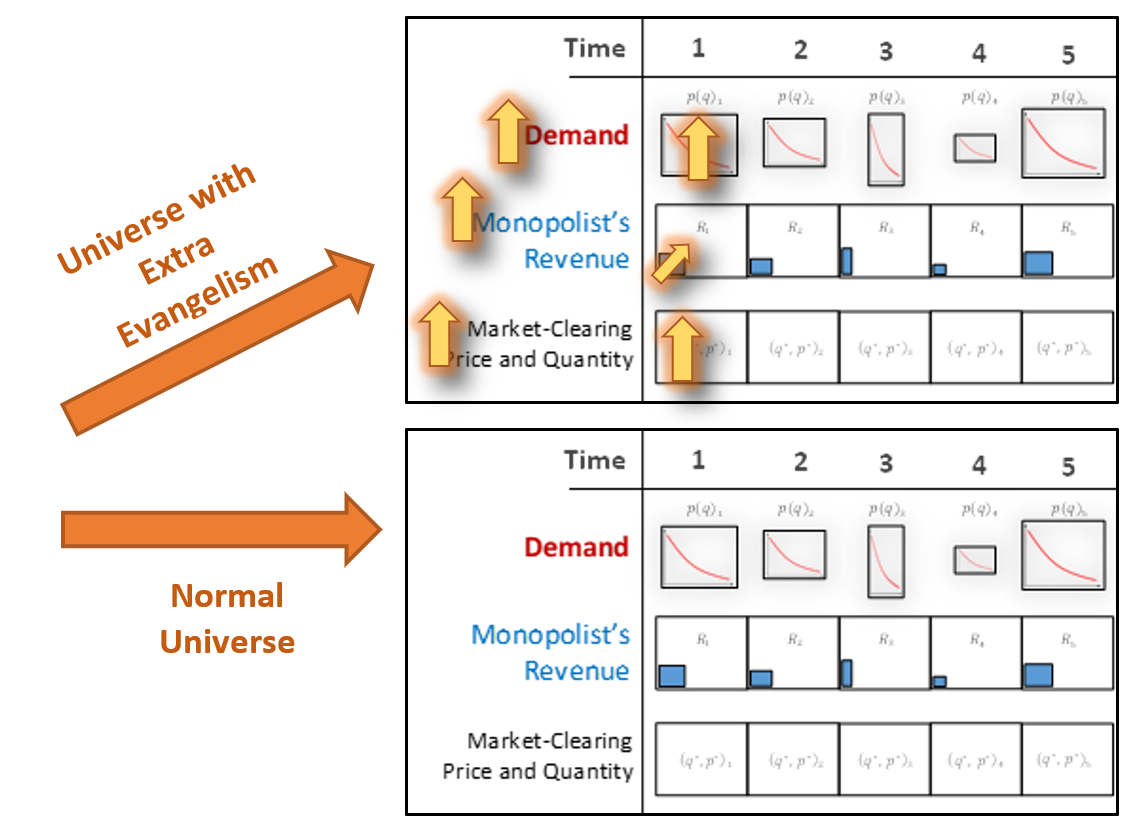

If someone, say Roger Ver, evangelizes for Bitcoin and therefore makes more people want more Bitcoin sooner, then the D’s will all increase, and in turn the q*s and R*’s will increase.

The reverse would be true if the history of mankind changed to disfavor Bitcoin. Perhaps, this would be because governments allowed the traditional banking sector to become more private or more FinTech-innovative.

The miners themselves may play a role in altering demand. For example, they may place us all into a history with bad events (such as extreme censorship of txns, or large block-reorganizations).

But notice that, so far, tx-selection is not in our story.

TX Selection

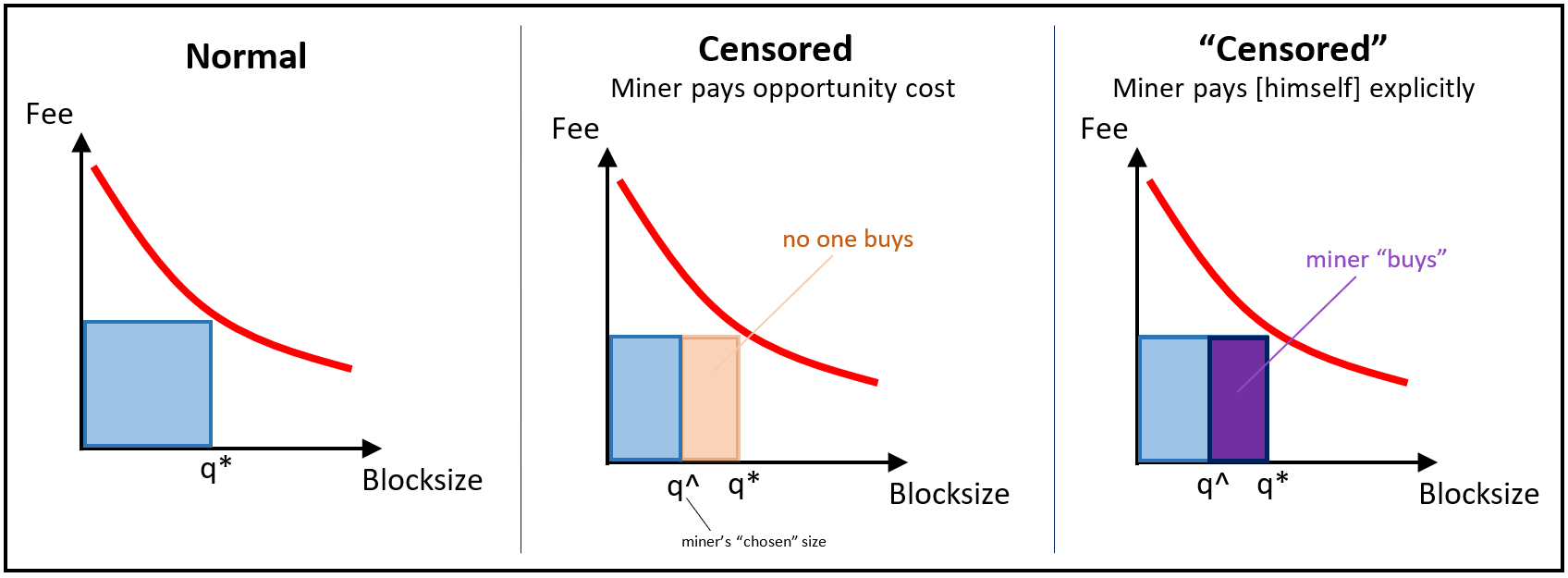

This is because, for a user who wishes to enter a block, there is no real difference between being outbid by another user, and being outbid by a miner. Within the context of allocating a particular unit of block space, a miner might as well be a user – they are fungible.

In the case of miner-censorship of txns, just replace the idea of a censored R* block, which a normal R* block in which the miner has paid himself for that blockspace.

And here is the crucial point: the “censorship” that miners do, can in fact be done by anyone. Anyone who pays for part of the R region owns it. It makes no difference if this person is a miner (paying an opportunity cost) or a regular user (paying an explicit txn fee).

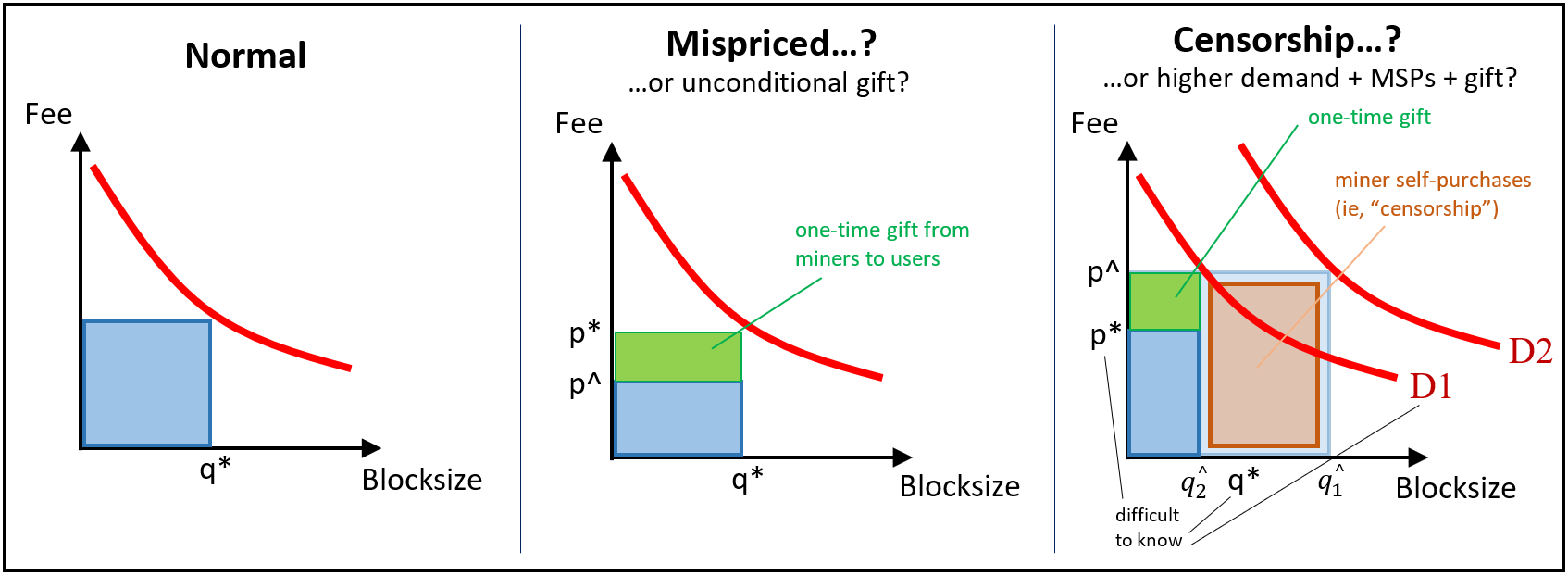

And this concept is not limited to the reduction of q at some arbitrarily-constant p. It extends to all combinations of p and q. This is because there are three things we don’t know (or rather, “can’t” know:

- The proportion of transactions that are made by users who are also miners (ie, the “miner self-purchases (MSPs)”).

- The true demand-level for blockspace, which may be moving upward. For example, it would if miners themselves suddenly were overwhelmed with a desire to transact.

- The extent to which miners are charitably keeping the current block’s transaction fees low, for some farsighted purpose (for example, to boost adoption or long-term growth), or alternatively for no purpose at all.

This concept even extends to cases where miners use suboptimal q* estimations (ie, where the {argmax_q R(q)} process is faulty).

We typically would say that the user is free want to use Bitcoin as much as possible. And, provided he or she is willing to pay, the user is free to transact as much as possible. But if miners are also users (which of course they must be allowed to be, in practice), then the idea that “miners control the content of blocks” must be discarded. They control the content no more than any other user.

More On Miner Control

Therefore, (within a given protocol) miners only control two things:

- Their local “parochial” features, such as their name, their location, their power costs, their capital costs.

- Their “broadcast strategy”

(Drivechain does add a third thing, but we will not discuss it here because it is discussed at length in the spec.)

The factors of the first group are, by definition, not part of a universal description of mining, and so they cannot be relevant to any claim about “mining” writ large.

The long-range 51% attack is a special case of the broadcast strategy known today as ‘selfish mining’ (originally known as “block withholding”). As far as I can tell, of all brodcast strategies this is the only one which affects users – the other broadcast strategies only affect other miners [at which point they immediately become uninteresting]. A user who follows the whitepaper’s advice (waiting for 6 confirmations; or fewer if txn is small or more if it is large), will only be affected by a >6 block reorganization.

Large Reorganizations

Thus, it seems that there is only one decision that a miner can make (other than his narrow, parochial profit-maximizing activities). And this decision is whether or not to engage in a long-range reorganization attack, using a very large portion of the hashrate (in order to engage in double-spending).

Such a reorg would be a kind of “nuclear option” of mining, and it is matched by the user’s nuclear option of changing the PoW algorithm. Because the miner’s option makes the network so unusable for users, users in turn have almost nothing to lose by changing the PoW. At least a PoW-change has a small chance of salvaging the network’s transaction-processing features.

Because of that, the miner’s decision is really between [1] operating normally, and [2] creating one double spend opportunity while destroying all of their hardware.

The question then becomes: is the double spend opportunity more valuable than the destruction of their hardware? The answer is overwhelmingly likely to be “no”. In fact, the double-spend opportunity is likely to be worth nothing at all, because the new spinoff will likely aim to extend the pre-reorganization longest chain (in which the double-spend did not take place).

Pre-Coordination

This decision could even be said to be “decentralized”, since it is plausible that every Bitcoin user who gave the large-reorganization scenario some thought would independently come to the conclusion that the PoW-algorithm must be changed. The only potential for confusion is [1] which PoW algorithm to switch to, and [2] which block should be the forking point. For these reasons, we should try to arrange things so that, upon the user’s signal, both decisions are made as automatic as possible. A predetermined list of hashing algorithms [perhaps even one of infinite length] would solve the first, and perhaps one parameter or a GUI window could solve the second.

Professional Misconduct

A final interesting fact to note, is that miners are (and should be) heavily policed by other miners. This is because the PoW Change dooms them all.

In fact, the block maturity period (one of my favorite parts of Bitcoin’s design) ensures that some representative set of miners will definitely suffer at least some damage as the result of any 51% attack or PoW change.

Conclusion

Any user is free to fill up a given Bitcoin block at any time. Non-miner-users pay an explicit cost; miner-users pay an opportunity cost. Blockspace is allocated to whoever wants the space the most; in practice it does not matter if users want it for a “normal” purpose or if miners want it for a “censorship” purpose.

comments powered by Disqus