Abstract

A pair of chains has “Imposed Mutual-Exclusivity” (IMEX) for a feature, if (and only if) only one chain can have that feature at a time. IMEX allows users to make investments in a feature, that pay off if that feature is better. Some keys to IMEX include: GARP, using the same PoW-algo for both chains, and launching one chain with an extremely low initial difficulty.

Part One – Problem

Crypto-communities have a curious property, that probably discourages innovation. In fact it may be the root cause of most of the “toxicity” and frustration within blockchain communities.

The property stems from a core feature of blockchains: the public UTXO-set. The blockchain knows who owns the coins; and the blockchain and all of its source code are known to the public. Therefore, we all know who owns every coin as well. (There is no possible way to build a blockchain otherwise – even exotic coins like Zcash have [by definition] a way of telling an invalid spend from a valid one.)

Armed with their own UTXO-set, and a rival’s open source software, crypto-communities can use ‘air-drops’ to transform themselves from one blockchain to another. The BTC-community could just import its UTXO set into Monero. Or the Litecoin community could import its UTXO set into Zcash. There is no inherent relationship between a crypto-community and its software!! Communities can change blockchain-protocols just as easily as you or I could change clothes.

Why is this a problem?

Well, the problem is: a crypto-community can reject an idea at first, and later (after the idea has been proven its merit elsewhere) profit by taking advantage of it.

This is wonderful for the hegemony of the original chain; but it is disastrous for the new, upstart chain. And it wrecks havoc on the incentives for innovation. While obstructing, the original community halts progress. And when they eventually adopt the now-derisked idea, they bankrupt anyone who invested in it back when it was controversial.

So, the skeptics are rewarded for being wrong, and the trailblazers are punished for being right. This is unjust, of course!

But, more importantly, it destroys the incentives for trailblazing. The upstart chain can never attract investors – if the upstart is wildly successful, then it will simply be copied and replaced. (And if the upstart is a failure, then it will fail to provide a return in the usual way.) Without investors, the upstart network has a nearly-insurmountable disadvantage. On top of that, it would likely have poor on-boarding (and poor infrastructure generally), and unreliable mining.

Above: Barriers to progress, represented metaphorically. From this page.

What we need instead is the reverse: for the risk-seeking, entrepreneurial trailblazers to be rewarded if they are right. And for the obstructionist skeptics to be punished if they are wrong.

Patents / Copyrights

To do that, we’d need something to that simulates the function of a “patent” or “copyright”.

Literal patents or copyrights probably won’t work. They are clumsy to enforce, expensive to obtain, and interfacing with the state’s monopoly on violence is just more trouble than it is worth. Especially in the blockchain world – blockchains are like a competing government.

Passive Mutual Exclusivity

If the upstart chain is substantially different from the original chain, then the upstart need not worry about imitation. Imitation would just be surrender – it would be deleting the aspects of the old chain that made it unique.

This gives us our first clue to imposing mutual exclusivity (in a case where the old and new chains are NOT substantially different, and where we therefore cannot rely on passive mutual exclusivity).

Part Two – Imposed Mutual Exclusivity

This section asks: What can the creators of the new chain intentionally do, in order to stop the old chain from stealing their good ideas?

I will call the feature in question “Feature X”, and the original chain “Old Chain”. I will use “New Chain” to refer to the upstart chain that takes a chance on Feature X. I will call users of each chain “Olds” and “News”, respectfully.

(I will also assume that Feature X is objectively net valuable, as otherwise there is no point to any of this.)

1. Deleting the Adversary’s Willpower

It would be ideal to placate the Olds – if placated, they will have less of a desire for revolution.

The obvious way to do this is…well, the hard fork already does this! Since the hard fork awards free UTXOs to all Olds, it ensures that Olds cannot become any poorer as a result of the fork’s success.

A GARP hard fork does even better, by ensuring that net worth is only affected by intentional speculative actions. GARP delays (as much as possible) the inevitable “unraveling” of the two UTXO-sets. The less-unravled they are, the less “pain” the OldCoin-community will feel, and the less likely they are to respond to NewCoin’s success by copying it.

With the Olds placated via hard fork, they have no reason to complain about “not having” a certain feature on Old. They do have it – just one New.

Because of this fact, any campaigning that Olds do (eg “we should copy the previously-contentious Feature X”) will probably be interpreted as mere greed – just special pleading from those who speculated poorly. And it will probably appear that way, because it is that way – users who genuinely want the new feature don’t need to campaign for a change, they just need to start using New. And New has already been provided, and Olds already have all of their coins there, waiting for them.

So our first IMEX principle is: use a hard fork, and use GARP.

2. Getting the Miners to Help

No matter what, New faces a best-case future scenario where speculators on Old experience regret. They will realize that they made a mistake in rejecting Feature X. They will then try to obtain Feature X. If they can do so, then IMEX is lost.

How can we disable something against the users’ will?

The only way is with the help of the miners. This is the second principle of IMEX: a mining “attack” plays the critical role.

Under normal circumstances, of course, a miner-attack is mostly a self-attack – once the crypto network is destroyed (relative to its rivals), the ASIC-equipment associated with it will be worthless. So we need to change the circumstance substantially, such that ASIC-equipment is still just as valuable after a successful attack.

That brings us to our next guideline of IMEX: New should retain the PoW-algorithm of Old.

Existing ASIC-owners will then be indifferent between Old and New. Their chip-investments should be worth the same, even if one of the two networks is completely destroyed by the other.

In fact, ASIC-owners should be indifferent to the location of the value-add of Feature X. The value-add could be on Old (in which case IMEX has failed), or it could be on New (in which case IMEX has succeeded). But either way, ASIC-owners will eventually capture this value-add. This is important, because otherwise we would dread the inevitable arrival of the time when it is widely known that Old’s price could be improved if Feature X were activated on it. But now we can ignore it, because New’s price can already be improved by at least exactly that much.

Below I place the market price of each coin on a vertical line. At the time of the fork, New (the upstart network) will be less-proven and therefore cheaper. I also sketch out “p3”: the (theoretical) price of a coin in the future (a future where Feature X is properly understood, and the “coin war” between New and Old is over).

---------------------------------------------------

p3 <--- Price of one single winner-take-all

| network, inclusive of the value-add

| of Feature X.

|

| <-- "delta 3"

|

p2 <--- OldNet price ($/coin).

|

|

|

| <-- "delta 2"

|

|

p1 <--- NewNet price ($/coin).

|

| <-- "delta 1"

|

0

---------------------------------------------------

Above, since I have assumed that Feature X is valuable, we see that Miners have some incentive to activate Feature X on Old. This incentive is labeled “delta 3”. However, if they can instead activate Feature X on New, and shepherd New to victory (over Old), then they stand to gain not only “delta 3”, but also “delta 2”.

I have shown that miners would prefer to win with New (vs Old). And I have previously shown that majority hashrate can block new features from being implemented. Thus, the hashrate on Old can create IMEX between New and Old, after which New will win, rewarding the miners. Have we succeeded?

No. There is a final difficulty, in the form of a free-rider problem: the miners who profit [on New], are different miners from the miners who block [ie, who will mine Old and prevent Feature X from occurring there]. The value-add is distributed unevenly, and actually requires sacrifice from some miners.

So, we need a solution to free-riding.

By way of illustration, notice that the problem would be solved if all miners were actually the same person. When you own the entire bus, paying for an individual bus ticket is really just some superfluous accounting. You are just paying yourself – you already own all of the tickets.

Similarly, there would be no problem if all of the coins were owned by one person. That person would find it most valuable to differentiate the networks, such that one had Feature X and one did not. Then, anything they learn about Feature X just affects the relative value of each network – it does not give the sole owner any new incentive to change either network.

Of course, we cannot achieve either of these extremes, in practice. But perhaps we can approximate both of them by encouraging miners to accumulate large concentrations of NewCoin. This can be easily achieved by setting the initial difficulty of New to be very low, which will allow vast quantities of coins to be mined by the earliest few miners. These individuals will then have a lot to gain, individually, by blocking Feature X. And so they might then turn their hardware toward the Old network and the blocking of Feature X. It is true that other, smaller owners would free-ride off of this blocking activity, but for our purposes we only require that someone with ASIC-equipment find the act of blocking to be more-profitable-than-not.

Setting the difficulty low brings to mind another IMEX source.

3. Killing The Old Chain Outright via Hashing Death Spiral

If New has a difficulty that is much lower than its expected equilibrium price, then all miners should turn their hashpower to it.

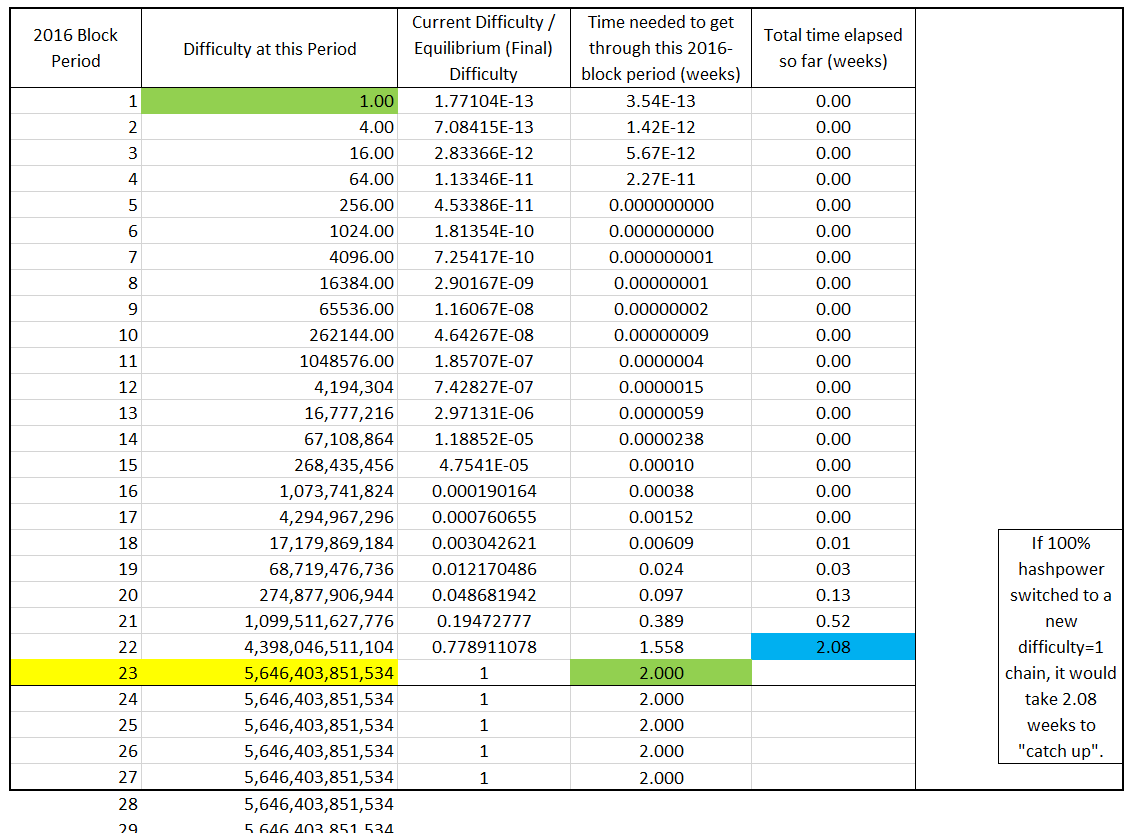

If the difficulty is much lower than the expected eq. price, then it should take very many difficulty adjustments to reach equilibrium. This is because difficulty can only increase by a factor of 4 each 2016-block period.

As a thought experiment, imagine that 100% of BTC’s current hashrate switched from the current network (difficulty=5.6 trillion) to a brand new network (difficulty=1). The new network would take 44,352 blocks (22 adjustment periods) to adjust the difficulty back up to an equal value (ie, to 5.6 trillion). In total, these adjustments would take ~2.08 weeks of calendar time. (It would take about 0.52 weeks to get roughly 78% of the way [to 5.6 trillion].)

During these ~2.08 weeks, the Old network would –theoretically– find zero blocks. So it would be disabled, and possibly killed outright.

Of course, this is an extreme oversimplification. This sort of doomsday scenario is talked about from time to time, and it never seems to pan out in the slightest.

But previous “death spiral” scenarios did not have good outcomes for ASIC-equipment. In contrast, this scenario sees ASIC-equipment actually increasing in value. (It has an immediate alternative use, in the form of the New network.) So perhaps it is different this time.

At any rate, it corroborates the advice of the previous section: the initial difficulty of New should be very low.

A more extreme variant of this advice, would suggest that New have a block subsidy that temporarily skyrockets during the critical “chain war” period. In other words, New might suddenly begin releasing a ton of new coins, roughly during the time when the Old and New networks start to have similar difficulty-levels as each other.

4. Defection-Rate > Learning-Rate

i. Intro

Ideally (for IMEX), by the time most Olds are interested in adopting Feature X, it would somehow be “too late”.

How could this be?

One way would be for a few Olds to become interested in X at a time. Each of them is in a frustratingly small minority, and so each is forced to defect. By the time new Olds learn of Feature X, the previous learners have long since moved on, to New. Over on New, various products and services have been created, each with their own new network effects.

ii. Triangular Logic

Let me begin by pointing out a “tangle” of three interrelated thought experiments:

- First, let us temporarily make the unrealistic assumption that each network magically has an equal shot at victory – ie, an equal shot at achieving p3 (above). It follows that the cheaper network is a better investment. So, paradoxically, being cheaper tends to give a network an edge with investors.

- Second, let us make a new unrealistic assumption: that the hard fork ‘New’ has already been somehow imbued with perfect IMEX. Then, the following property would seem to now hold: the New network will remain cheaper for exactly as long as Feature X is misunderstood by most people. Once Feature X is understood properly, the New network will be more expensive. So, if there’s IMEX, then being misunderstood goes hand-in-hand with being cheaper.

- Third, remember that ignorance of Feature X is itself a form of IMEX. Olds can NOT copy Feature X into their project until after they figure out what it is [that they should be copying]! If no one ever understands X, then Old will never be able to want it, or even think about it – only after X is learned can it be copied. So, being misunderstood grants IMEX temporarily (we need it permanently).

These three facts form a kind of triangular, rock-paper-scissors-style tangle of interrelated ideas.

Misunderstanding --> IMEX

^ \ \

| ----------> Cheaper ---> A Better Investment ------

| |

| |

| |

| |

----------------------------(negative)--------------------------

The lower arrow represents the fact that, as something becomes more popular (as an investment), it will become better and better understood.

We would need to make progress on the “upper part” (the positive feedback cycle of success), while somehow obstructing progress on the “lower part”.

iii. Heterogeneous Learning

I think this progress might take the form of learning heterogeneity – ie, if some users learn Feature X faster than others.

For example, imagine that a hard fork occurs on Sunday.

- On Monday, some users (call them “the Mondays”) intentionally split some of their funds off, to invest in New at the expense of Old (and to make use of the new Feature X)1. They are certain that Feature X is the way to go. Plus, at this early stage, the new chain is much cheaper (than the old chain). Cheaper means: more upside for them.

- On Tuesday, a few users –who were previously skeptical– now start to see the merits of Feature X. They may try to persuade other Old Users of their newfound discovery. But recall that I assumed that some people are faster learners than others. So their efforts to achieve persuasion will be minimally effective. Most people just aren’t as fast learners as the Tuesday-learners (or Monday-learners). So the Tuesdays move some of their funds from Old to New. Mondays notice this, and move some MORE of their funds from Old to New.

- On Wednesday, a few more users –who were previously skeptical– will, for the first time, clearly see the merits of Feature X. They will face the same dilemma as the Tuesdays: that persuasion is difficult. Let us imagine that, again, everyone invests just a little more.

- On Thursday, let us imagine that the left-midsection of the bell curve learns, for the first time, of the Merits of Feature X.

These Thursdays are now in an interesting position. The new chain is “better” (it has Feature X), and cheaper. The Thursdays can expect that, by tomorrow, they will be joined by the right-midsection of the bell curve, and constitute a large majority.

If Thursdays and Fridays team up, they can do whatever they want.

But what do they want? How will the Fridays behave?

Now, the degree of heterogeneity will matter tremendously for this next part. So watch for it.

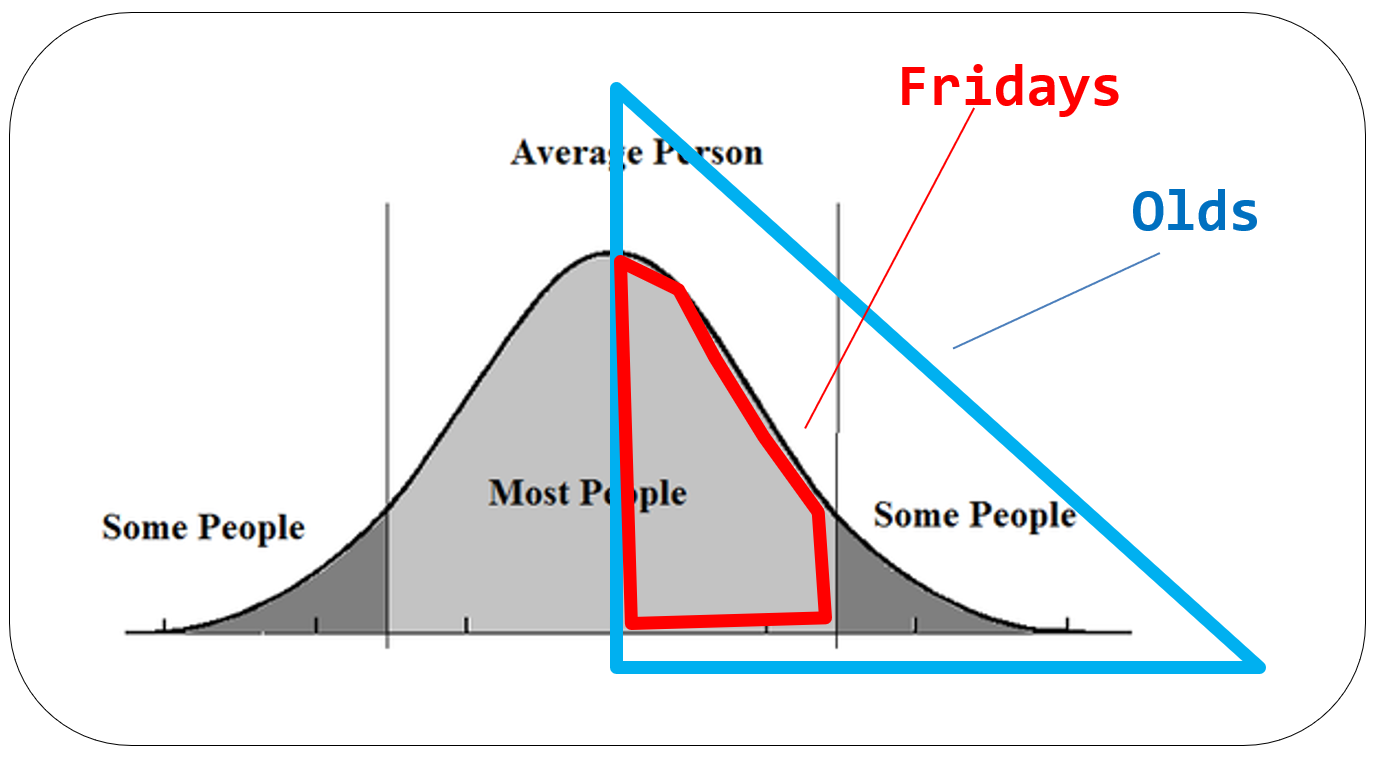

First, we’ll imagine that the degree of heterogeneity is low; such that “large groups learn all at once, in big bulky ensembles”. Tomorrow, on Friday, the next big group of Fridays will learn of X. At that point, they will discover that they are a majority of the remaining “Olds” (but not a majority of both “New + Old” networks simultaneously).

Above: Distribution of ‘how long it takes for people to appreciate Feature X’. The fast-learners are on the left, and slow-learners are on the right. Most people are medium-speed-learners, in the center.

Since they are a majority, they might be able to get Feature X merged into Old. If they do, IMEX has failed.

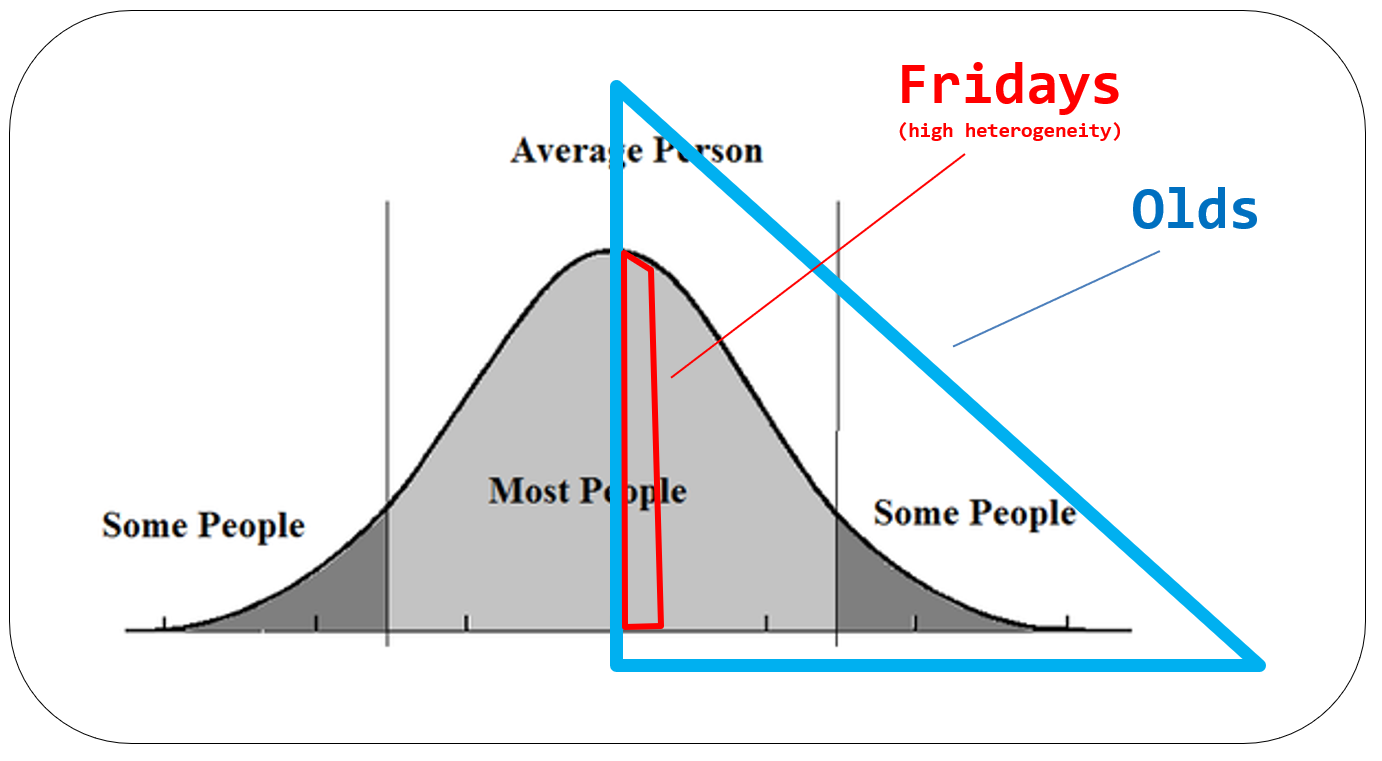

But instead, however, let’s imagine that the degree of heterogeneity is high. Then the Fridays will still be in a minority (shown below).

If all Fridays wait patiently, of course, they will eventually be part of a majority coalition. But if some Fridays jump ship (from Old to New, ie take advantage of the opportunity to increase their hodlings of New-BTC), then this majority coalition will be slower to arrive. And if all of the new converts jump ship (at a fast enough rate), then the majority coalition will never arrive. And so IMEX will be achieved.

iv. How to make use of this?

Above I have discussed “learning heterogeneity”. As a concept, it is hard to measure and/or manipulate.

Instead, we might manipulate the “defection rate”. By doing this, we shorten the “periods” – ie, instead of Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, we would have Monday 8 AM - 9 AM, Monday 9 AM - 10 AM, Monday 10 AM - 11 AM.

We could do this if everyone decided to defect, as soon as they learned of the merit of Feature X.

If everyone defects quickly, then, in general, everyone will profit at the expense of the obstructionists (who will suffer) – which is exactly what we want.

So the advice, rather clumsy though it is, would be: make sure that investors know that they can profit more if Olds remain ignorant.

(Added 9/2020)

i. “Don’t Buy Monero” – MarketCap as a Media Monopoly

Ideally, it would be impossible for Olds to ever understand Feature X – or else, they must always regard it as something inherently evil.

Therefore it is ideal for supporters of NewCoin to all pretend to be OldCoin-maximalists, and pretend to be haters of Feature-X. When people convert from Old to New, this must be kept completely secret. NewCoin-supporters must go about their former “Old-shaped” lives, pretending to be loud OldCoin-supporters, and pretending New doesn’t exist. Hatred for New must be seemingly unanimous.

It must be a known part of the NewCoin conspiracy, that it has no official supporters at all. Therefore, the only way of gauging NewCoin-support would be to look at New’s marketcap. This is ideal for IMEX, as the marketcap itself is a measure of likelihood of sustaining IMEX (if IMEX cannot succeed, then the marketcap will stay low). Thus it keeps everyone –supporters and detractors– on the same page: everyone knows only the tautology that that “NewCoin has not succeeded yet”. And, as previously mentioned, a low marketcap attracts supporters, because of the additional profit opportunities.

ii. Aggressive Branding

One straightforward way of achieving IMEX would be to label the two coins in relation to Feature X. So, for example, the BCH-ers could have called BTC “Bitcoin 1-Meg” or “Smallblock Bitcoin” (instead of “Bitcoin Segwit” or “Bitcoin Core”).

This would create an expectation that the two networks would always be different in exactly this single pre-specified way. Better still, this expectation would tend to grow stronger over time.

iii. Those Entering the Game Mid-War

The time of the coexistence of the two coins, will be inconvenient for new investors, who will prefer to invest in just one coin – generally: the larger coin, aka OldCoin. Obviously they then become natural enemies of NewCoin and of IMEX.

The ranks of such people, must be depleted as much as possible. Culturally, this might be done by promoting the idea of “owning both sides” of the fork (which should initially be cheap). Unfortunately, this requires a strong media campaign from NewCoin. But investors are familiar with the concept of “schmuck insurance”, and of hedging. And they all understand “no free lunch”, “risk and reward”, etc. Plus, GARP will be making the two coins appear equally popular. So, the crucial thing is that newcomers know that NewCoin exists.

Best for New, of course, is to prevail as quickly as possible. The longer the “war” goes on, the steeper New’s disadvantage. Of course, opponents of Feature X will make it their mission to delay New’s victory as long as possible. The best way to counter that is for Feature X to be very user-friendly, easy to understand, and to have lots of happy users. However, that may not be possible until NewCoin actually launches! So: NewCoiners will have to move fast – the first 30 days will be critical. The 90 days before that, even more so! In general, anything that helps people learn about New will be helpful to New – memes, subreddits, long delay before activation, and so forth.

If the war is long, and these OldCoin-newcomers do arrive in sufficient numbers, then they must be discredited as much as possible. One way, would be to suggest that OldCoin-only-newcomers were negligent in their research, and are now asking for a handout. Like the “SFYL” meme. A second way, would be to suggest that Oldcoin-only-newcomers are actually ardent NewCoin supporters who are just pretending. Thus, each True newcomer would think that they were the only person not ‘in on the joke’, and each would thus become somewhat marginalized.

Conclusion

Competition improves all things. But one paradox of competing with Bitcoin is that a new valuable idea must be: [1] very similar, and [2] unique. If it is not similar, it will imperil the developer network effects. If it is not unique, then it can be copied into Bitcoin (and so it can never be seriously tried, and therefore never proven to work).

Above, I suggested ways to help a new, valuable, similar idea to establish its uniqueness. They were:

- Use GARP (to make users indifferent).

- Keep the same PoW-algo (to make miners indifferent).

- Launch the network with an ultra-low difficulty level (to give some users strong incentive to shoulder the burden of critical IMEX-maintainance).

- Focus on defection, not persuasion.

If you can think of anything else, please leave it in the comments!

Footnotes

-

Recall that GARP allows users to invest/divest themselves of a chain, even if no exchange decides to list it. ↩