For a “payments chain”, how large would the blocksize need to be? And what kind of fees would be competitive?

A Payments Chain

GigaChain (GC) is a blockchain design. It is ultra-easy to make, and [probably] very useful.

Specifically, it is Bitcoin Core with two changes:

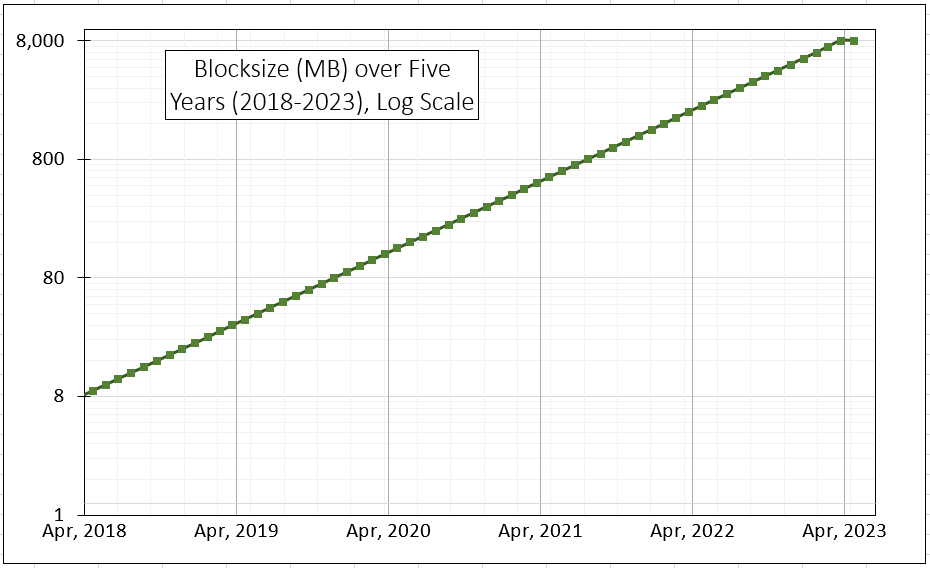

- “Enough” Block Space – 8 MB growing to 8,000 MB over the next 5 years.

- [optional] Mandatory Minimum Fees – of about 25 cents per txn, to discourage freeloading.

It is designed specifically to compete with VISA, being cheaper and faster1 while servicing a similar transaction load. (Of course, the larger blocksize will make the software more computationally intensive, and this must either be addressed with more expensive hardware or better engineering – those challenges are not the focus of this small piece.)

GigaChain is an alt-chain, and therefore might be an Altcoin or a Sidechain. As a sidechain of Bitcoin Core, GigaChain ends up as a highly ironic implementation of the “plexiglass window” concept of Peter Todd’s “Keep Bitcoin Free” video, because it meets his criteria:

- Keeping txns “off” of the Bitcoin Core blockchain.

- Use of technology for full transparency and fraud prevention.

In this case the “bank” happens to itself be a second, separate blockchain. As I explained at Scaling III there can be synergy among a “small-large” pair of chains. Indeed, my opinion is that only sidechains can resolve the blocksize conflict.

Codebase Notes

Let me briefly mention that GigaChain is a planned GitHub fork of the Bitcoin Core project.

The codebases will be identical (more or less), for as long as possible. Every additional line of code that GC requires (which will be very few) will be factored into its own separate files. Every line of code that needs to be deleted will instead be commented out. So the only difference in codebase (even visually) will be these new “include” statements, and their corresponding files.

This is to make it as easy as possible to maintain the project with minimal effort. We will wait for a new Core release, and then just click on “merge” to move in the changes.

In this way, I can guarantee that GC will have very good code. More importantly, I can prove that GC has good code, to third parties, as I evade the associated problems (ie, situations where poor users ask themselves “How can I know the difference between good and bad code, anyway?”). Not only do I neutralize “dream team” arguments, but I also neutralize the developer’s veto – it is impossible for a Bitcoin Core developer to “choose” Core over GC, or vice versa. Every Core developer is also a GC developer, whether they like or not. It’s a win-win.

If any dev wishes to make a change to GC, they should instead (try) to make that change to Core. If merged into Core, the change will then automatically sync over.

Eventually, I expect corporations (the whitepaper’s “businesses that receive frequent payments”) to build their own versions, optimized for the challenges of large blocks. But for now, any improvement to the codebase is probably just an improvement in general.

Now let’s talk about the two changes.

1. Blockspace

Matching the credit card industry.

Here I have compiled some information (sources below) on VISA transaction processing (in “transaction per second”, or TPS):

| Year | Max Possible | Max Actual | Avg Actual |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 24,000 | 11,000 | ? |

| 2011 | ? | ? | ? |

| 2012 | 30,000 | ? | ? |

| 2013 | 47,000 | 15,000 | ? |

| 2014 | ? | ? | ? |

| 2015 | 56,000 | 18,500 | 2250 |

| 2016 | ? | ? | 2630 |

| 2017 | 65,000 | ? | 3523 |

Terms:

- “Possible” is the technological capacity when the transaction network is being stress tested in the lab.

- “Max Actual” is the TPS rate on the busiest day of the year (December 23rd).

- “Avg Actual” is the total number of transactions in a calendar year, divided by the total number of seconds in a calendar year.

Sources:

- visa.com/blogarchives

- abhishek-tiwari.com/reflections

- Visa Fact Sheet Jun 2015

- Visa Annual Report 2017

We draw a few conclusions:

- VISA’s tx-processing tech grows consistently and exponentially.

- VISA never really uses more than one-third of this processing capability.

- Demand for tx-processing is very uneven – it comes in large concentrated bursts.

VISA in 5 YRs

Our goal is to grow GigaChain into a VISA competitor within five years. How will VISA-net look in 5 years?

For “Possible”, we can impute an annual growth factor of 1.153:

( 65,000 / 24,000 ) ^(1/7) = 1.153

Which implies a value of 152,000 TPS after five years:

65,000 * 1.153^5 , in end of 2023

Our Target

At 600 seconds/block, 152 kTPS comes to 9.12e7 tx/block.

And, at 250 bytes/txn, this comes to 22.8 GB/block.

However, we have some facts to consider:

- VISA only ever uses (1/3) of its maximum capacity (on its worst day), and its average throughput is (1/20th) its burst throughput.

- Bitcoin will have many “aggregators” in place by that time: namely Coinbase/BitPay as well as the Lightning Network.

- Bitcoin can actually work with VISA, for many txns. Users might shop normally, and then pay their monthly bill with a single on-chain BTC txn.

Therefore, I think the appropriate target is 8 GB/block. This would be more than enough block space to completely displace VISA, as it corresponds to 5.3% higher than one-third of the 22.8 GB figure.

I will start BX off at 8 MB/block, meaning that total Bitcoin transaction capacity (mainchain + sidechain) will exceed that of Bitcoin Cash.

2. Fees

This part is optional.

Why impose a minimum fee?

Well, each txn must be processed by all nodes. But each txn will only pay a fee to one node. All of the others are held liable for transactions to which they are a third-party. Therefore we have an externality problem – each transaction “pollutes” the blockchain.

The ideal way to address pollution would be to “internalize the externality”, by forcing each transactor to fully compensate every member of the network for the inconvenience of downloading/validating/storing/broadcasting his transaction. Unfortunately, not one has the slightest idea as to how this might be done, and many believe the task to be computationally impossible.

A second-best solution is to try to limit the network to its “natural” carrying capacity. This is one of the many functions of the block size limit in the first place. Imagine a fisherman extracting fish from a lake: if too many fish are extracted, the population will die. Also, for reasons which (I assume) are particular to the frequency/cost of “fish birth”, relative to the frequency/cost of “fish maturity”, laws exist to prevent fisherman from harvesting fish who are too young/small. Thus, if the lake is used more efficiently, the lake might tend to contain “more large fish” on average, and so its carrying capacity (in terms of fishweight/year) might rise.

So, we want to avoid a situation where a miner is tempted to mine an “inefficient block”, where this is defined as a block containing many low-fee txns. If users are unwilling to pay a minimum fee, this may indicate that they don’t appreciate the resource of blockspace.

Therefore, we might want a typical txn (250 bytes) to cost at least2 some amount.

A second reason to favor a minimum fee, is that sidechains have no block subsidy. Altcoins can have their txns subsidized by an inflation tax, but sidechains cannot. In the very long term, Bitcoin’s subsidy will run out and the network will need to sustain itself on (floating) txn fees alone. While this is a good plan in theory, it has never been tried before in practice.

A third reason for mandatory, BTC-based pricing, is that it is a rare example of a Bitcoin-based “unit of account”. I think it sends a good message to the world about taking Bitcoin payments (and Bitcoin-as-intrinsic-value) seriously.

Choosing a Competitive Fee

I conjecture that the typical txn should cost at least 0.25 USD. This would come to a rate of 10 satoshi per byte, assuming a constant exchange rate of 10,000 USD per BTC (more about that later).

Compared to VISA, this fee is extremely competitive. I highly encourage everyone to visit this site and examine their breakdown of VISA tx fees. It is quite obtuse, and I even shuddered while reading it, despite multiple graduate degrees / work experience in mathematics, finance, and economics. I must say, after my years of Bitcoining, I found VISA’s parade of arcane fees to be…almost claustrophobic. The bottom line is that VISA charges about $0.25 plus 1.85% per txn. Yikes!

So even for multi-input txns, which can be 500 or 700 bytes (and therefore 0.50 or 0.70 USD), we are really doing quite well. That 1.85% really adds up – even for $2.00 coffee (likely the smallest VISA txns today) it tacks on an extra $0.04. For a $20 StarBucks gift card it is $0.40.

Defending Against a Spam Attack

Since capacity and fees are fixed, let us consider the case where a disinterested third party intends to blockade the network by purchasing all the block space for themselves.

At 10 sat/byte, filling an 8 MB block would cost $8,000. And filling an 8 GB block would cost 8 million USD.

Miners could of course fill up a block with ‘circular txns’ which pay transactions from themselves to themselves. And therefore they can create any size block for “free”. (Of course, in that case the miner would pay an opportunity cost instead of an explicit cost.) On top of this, any attacker (miners included) must devote 8 million USD worth of capital to the ‘circular txns’ project, for the duration of the attack.

Dynamic Fee (As Exchange Rate Changes)

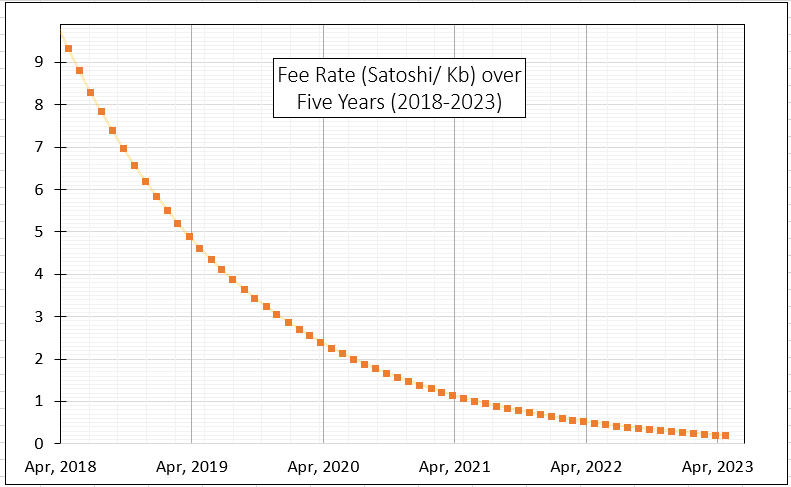

If the USD/BTC exchange rate increases dramatically (as it often does), the fact that the 10 sat/byte fee rate is fixed, will cause the effective USD/txn rate to increase.

This quite a problem to solve! The only way may be a very simple one: have the required minimum fee rate (sat/byte) fall slowly over the five years. Then have it go away (or become an optional soft limit).

If the exchange rate increased by three orders of magnitude, from $10 thousand to $10 million, it would imply that Bitcoin had displaced just about all of the fiat currency in existence.

But hey, a guy can dream, so let us have the fee fall by three orders of magnitude3 over 10 years.

"Three orders of magnitude" is 10^-3

"10 years" is 120 months

Thus the monthly rate:

10^-3 = x^-120

-3 log(10) = -120 log(x)

(3/120)=log(x) ; x = 10^(3/120)

x = 1.059254

Thus the monthly decline factor is ( 1/ 1.059254 ) ...

...which is roughly a 5.6% decline per month.

Thus, the typical txn will always cost $0.25 cents (nominal), even if the 2023 price of BTC skyrockets to $10 million.

Under this schedule, the minimum fees can only become prohibitively high (ie, “un-VISA like”) in worlds where Bitcoin is already destroying the existing financial infrastructure.

Footnotes

-

Unfortunately, because of the Scaling Polarization and rise of two “one-party states”, there is some controversy about confirmation times, and something called “replace-by-fee” (RBF). Firstly, credit card txns are much slower than Bitcoin txns: both are provisionally approved at roughly “email speed” (ie, in a few seconds), but a Bitcoin confirmation will settle over 1-2 hours, whereas a CC txn will settle over 750-1500 hours. Concerning RBF, some people will advocate for “removing it”, on the grounds that it will make 0-conf txns “faster”. These people are spreading misinformation and should be despised. Nevermind the numerous benefits of RBF for keeping fees down and liberating doomed transactions, and nevermind its nonexistent drawbacks, the true response to this anti-RBFers is that RBF is completely optional. When the merchant asks for payment, they can simply request a non-RBF payment. So, everyone’s happy. ↩

-

Minimum fees are enforceable, unlike maximum fees which can be circumvented with out-of-band payments. ↩

-

It is possible to charge a fractional satoshi/byte rate – we’d simply round up to the nearest satoshi. At 0.00041 sat/byte, a 500 byte txn would cost 0.205 satoshis, which we would need to round up to 1 satoshi. It takes 100 million satoshis to make up a whole BTC, so even at a price of $10,000,000/BTC, one satoshi is a mere ten cents. ↩